Screening guidelines for breast cancer have recently changed, and vaccines are in the works. Here’s the news! And, more importantly, the “why” so you can make evidence-based decisions.

The age to start screening is now 40 years old

Last week, the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF, volunteer panel of national experts) released new guidelines for breast cancer screening: Younger women should get screened. Specifically, those assigned female at birth who are at average risk of breast cancer should get a mammogram beginning at age 40 and ending at age 74. (NOTE: Guidelines are different for high-risk women, such as those with family history or genetic predisposition. Not sure? Try this risk assessment tool.)

The science around who should get screened for cancer and how often is always evolving—in part because technologies and patterns of cancer continue to change. Policymakers are charged with routinely weighing the evidence on benefits and harms of screening. Detecting a cancer early can potentially make a huge difference in prognosis and burden of treatment, but it can be hard to demonstrate what didn’t happen. Potential harms include false positives and treating “pre-cancers” that wouldn’t necessarily have becomes a problem (called overdiagnosis) and the related physical, psychological, and financial impacts. This benefit/harm balance has been debated for years, mainly because of the uncertainty of numbers (e.g., lives saved vs. overdiagnosed).

Before the recent change, USPSTF recommended starting screening at age 50, which was controversial and disagreed with a number of other organizations. For example, the American Cancer Society (ACS) recommended everyone start screening at age 45.

Several factors drove UTPSTF to recommend screening at younger ages:

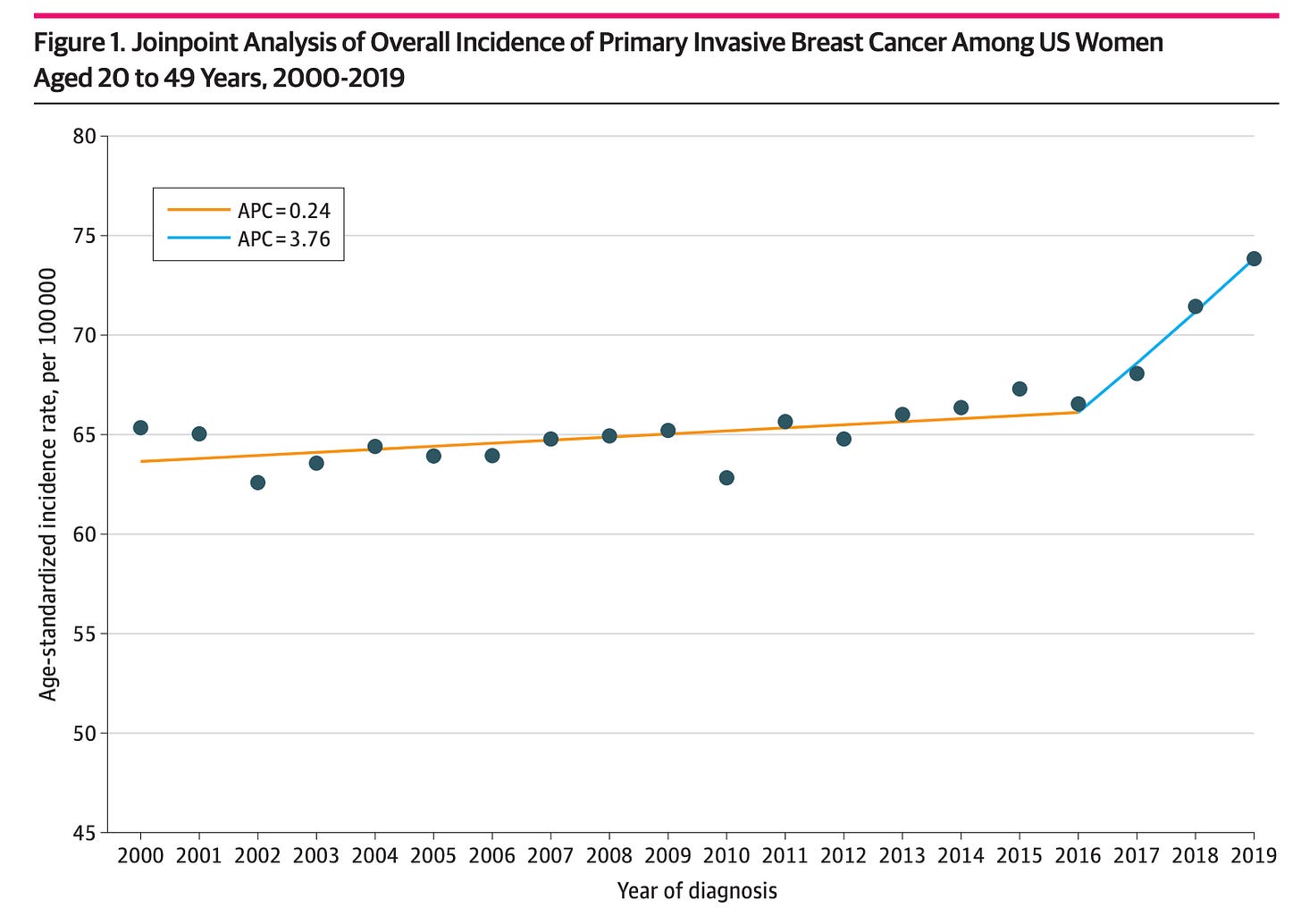

Breast cancer is increasingly occurring at younger ages. It’s estimated breast cancer in people under age 50 has increased by 2% each year, and more rapidly in recent years. Breast cancer is typically more aggressive when it occurs in younger people (before menopause in particular). Because cancer has typically been thought of as a disease of aging, younger people often don’t discover cancer until it is more advanced.

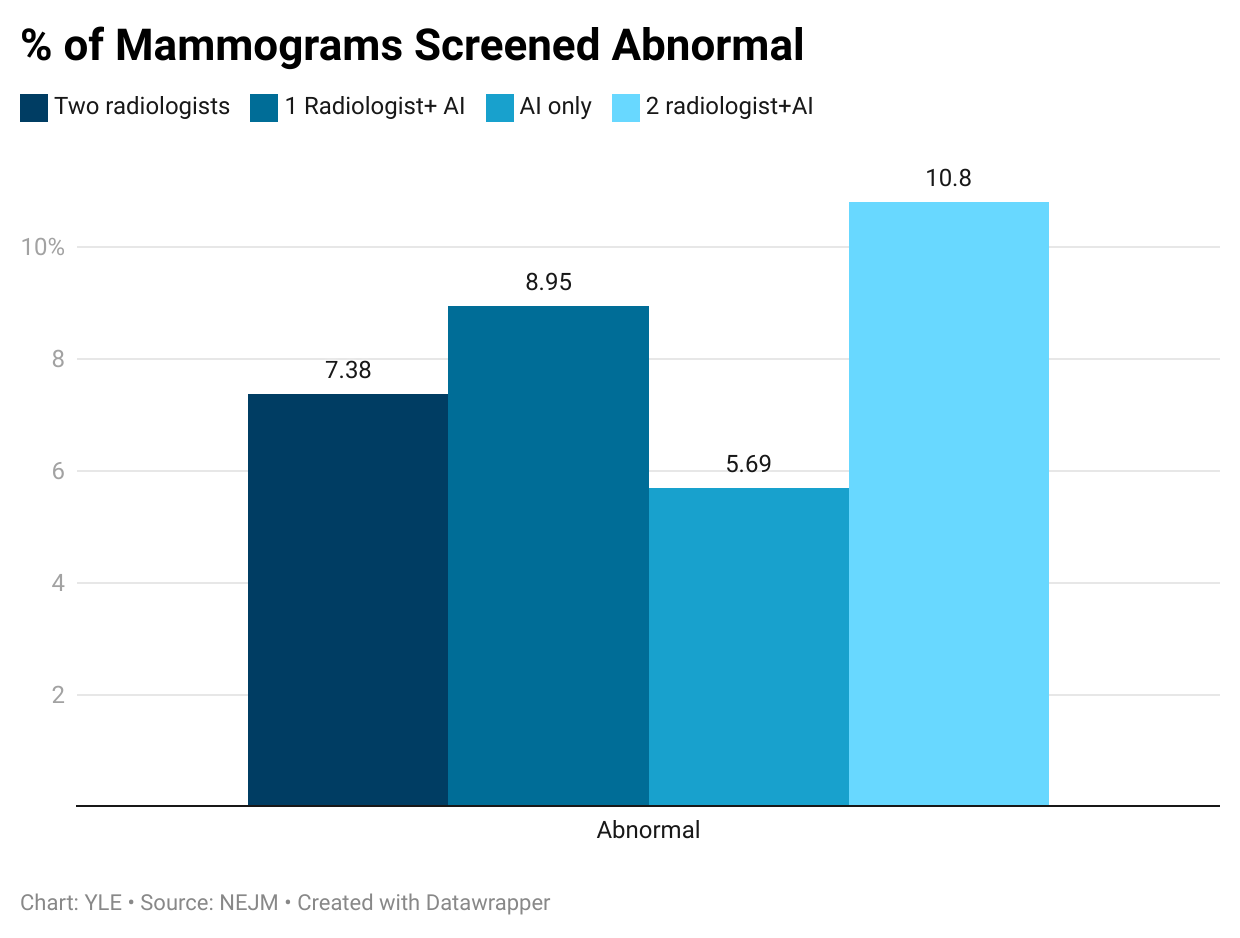

Technology improvements such as 3D mammograms have made screening more effective in identifying cancers. This is important because it reduces overdiagnosis and the psychological distress related to an abnormal result. We are curious to see how AI can help with this, too. For example, a Lancet study showed a modest increase (4%) in cancers detected when a radiologist+AI looked for cancer on a mammogram compared to two radiologists.

Strikingly high breast cancer mortality among Black women, in particular, could be reduced by earlier screening. A recent study projected that beginning cancer screening at age 40 would reduce cancer deaths among Black women by 24%. This is crucial since Black women have higher mortality from breast cancer than women of other races or ethnicities.

How often to screen is up for debate

Although the ACS and USPSTF now agree on younger screening, they still disagree on some specifics, including how often to screen. USPSTF recommends doing so every other year, while ACS recommends an annual mammogram once you’re 45. (The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, or ACOG, lands in the middle.)

This is a problem. Conflicting recommendations create confusion, leading to population-level patterns of delay. In addition to absolute benefits and harms, policies and guidelines should incorporate evidence on human behavior (AKA behavioral science). For example, preventive health behaviors are easier when guidelines are clear, behaviors are simple, and the timeframe is reasonably narrow. I can probably remember when it’s been about a year since my last mammogram, but two years? This shifts more burden to the health system to track my mammograms and remind me. Critically, guidelines also inform what insurance will pay, and out of pocket costs can be a huge hindrance.*

Breast cancer vaccines?

Even if detected early and treated, some cancers can recur or spread and, in the process, mutate to become more resistant to treatment. This stubborn process has driven scientists to try and develop vaccines to prevent and/or achieve durable “immunity” to cancer.

One form of breast cancer called triple negative breast cancer, or TNBC, is more difficult to treat because there are fewer “targets” for currently available drugs. The Cleveland Clinic has been working on a breast cancer vaccine for 20 years that trains the immune system to identify and destroy TNBC cells, which secrete a protein called alpha-lactalbumin.

Preliminary results from the first portion of the phase I clinical trial were presented in April 2023. The scientists enrolled TNBC survivors who were at risk of their cancer returning.

The purpose of this trial was to test safety, but scientists also looked at immune responses. All participants built some immune responses, and the vaccine was safe.

There’s a long way to go to show an impact on TNBC, and many larger breast cancer vaccine trials have failed to get a vaccine to market. Still, we’re keeping an eye on this space, and keeping our fingers crossed.

Bottom line

Get your mammograms starting at age 40. It’s likely easier (and more proactive) to do it every year, but you can weigh the potential benefits and harms for yourself. (And talk to your insurer/provider about cost.*)

Love, YLE and AB

*Updates to the original post thanks to insightful reader comments!

Andrea Betts, MPH PhD, is a behavioral scientist whose research focuses on cancer in adolescents and young adults.

“Your Local Epidemiologist (YLE)” is founded and written by Dr. Katelyn Jetelina, MPH PhD—an epidemiologist, wife, and mom of two little girls. During the day, she is a senior scientific consultant for several organizations, including CDC. At night, she writes this newsletter. Her main goal is to “translate” the ever-evolving public health world so that people will be well-equipped to make evidence-based decisions. This newsletter is free, thanks to the generous support of fellow YLE community members. To support this effort, subscribe below:

Don’t forget, though, that the varying recommendations also impact whether insurance will cover annual mammograms under age 50. While the frequency and timing of preventive screening should be a discussion and shared plan of care between a patient (all biological women, regardless of current gender identity) and their medical team. But few patients will follow a regimen if their insurance plan doesn’t cover the screening and the out of pocket cost is hundreds or thousands of dollars.

When academic and specialty societies agree on a standard of care, they are more successful in advocating for coverage of that standard by all insurance plans thus reducing health disparities.

I currently have several friends (between 45-70 yo) who have breast cancer. Two had clear mammograms one year and cancer the next (resulting in surgery for both, radiation and chemo for one). A third opted for treatment upon discovery of a stage 0 breast cancer. One mentioned that she had not been getting the 3D mammogram, and that this might have been the reason for a delayed detection (she had 5 tumors in one breast). Apparently her insurance charged $50 for the 3D mammogram, whereas it's covered annually in my plan. We all have dense breast tissue. Once, I was called back for a follow up sonogram after the mammogram yielded inconclusive results. A couple of other times I was called back for a follow up mammogram. My hope is that screening improves, in particular for populations for whom mammograms aren't great at early detection. It's essential that access to screening be consistently and affordably priced across health insurance plans, too.