Recently, there’s been considerable chatter of increased gun violence in the United States. The Washington Post recently ran an article entitled “2020 was the deadliest gun violence year in decades. So far, 2021 is worse”. NPR also had an interview entitled “Understanding 2021's Rise In Gun Violence”. So on and so forth.

And it’s not a far fetched hypothesis.

A rise in gun violence could make sense. For a few reasons:

Behaviors are changing. Most obvious is that we are opening up after a year and a half away in our homes. This coupled with financial strain, rise in inequality, and trauma increases tension and, thus, can increase interpersonal violence.

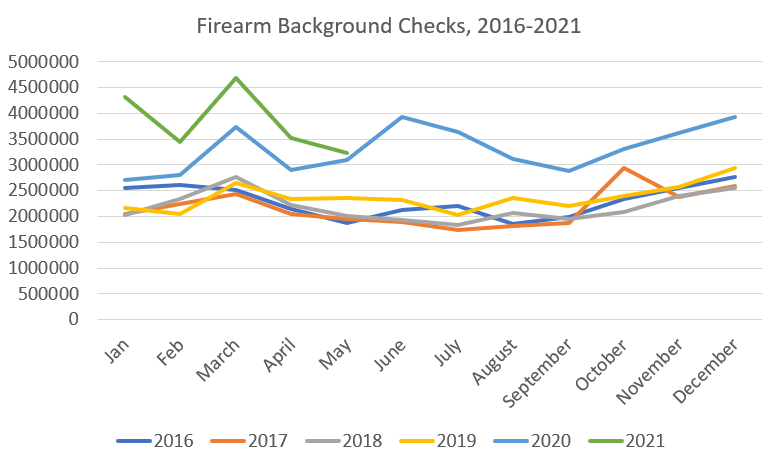

Gun sales are up. The pandemic (and an election year) had an interesting impact on firearm sales. In fact, 2020 (and now 2021) has the highest rate of firearm background checks. Ever. Marry this with increased stress can equal a very dangerous situation. But an increase in guns doesn’t necessarily mean an increase in new owners or an increase in deaths/injury. Also, black market guns could tell a very different story (we just don’t have the data to know).

Nature of crime. A critical question is the nature in which the firearm is being used. Are they being used in a violent crime? And, is violent crime up? We don’t have a good data for this. But we are seeing anecdotal reports from police departments. For example, the Chief of the Miami Police Department (who is also the former chief in Houston and Austin) verified homicides are up 9.3% in Miami and forcible sex offenses are up by 28.4% since last year. In May, there was also a 28% increase in homicides in Philadelphia, 76% in Tucson, 23% in New York. But anecdotal evidence in one or two communities isn’t necessarily reflective of an entire nation.

Decline in police patrols. Another possible contributing factor is coined the “Ferguson effect”. Basically, it’s the idea is that police officers may become hesitant to be proactive out of concerns for being subjected to negative media scrutiny for racial profiling or the use of excessive force. The hypothesis is that reduced police engagement and lack of enforcement—if widespread enough—could lead to increases in violent crime. In the past, scientists have found no such effect on a national level, but rather a noticeable effect on a local level (here). For example, we’ve seen it in Cincinnati (here) but not in Los Angeles (here). I could talk hours about the Ferguson effect…maybe for a future post.

Given these hypotheses, is 2021 the most gun violent year?

The problem is we just don’t have good data on a national level. There are really only two data sources each with their own limitations.

First, we have the Gun Violence Archive. This is run by a non-profit that was started in 2013. They collect gun violence incidents from 7,500+ law enforcement, media, government and commercial sources daily in an effort “to provide near-real time data about the results of gun violence”. They need some help (GVA-call me!), but they do a decent job at passive surveillance. Especially given really no one else is doing it.

The aforementioned headlines stemmed from GVA. For example, the Washington Post article stated:

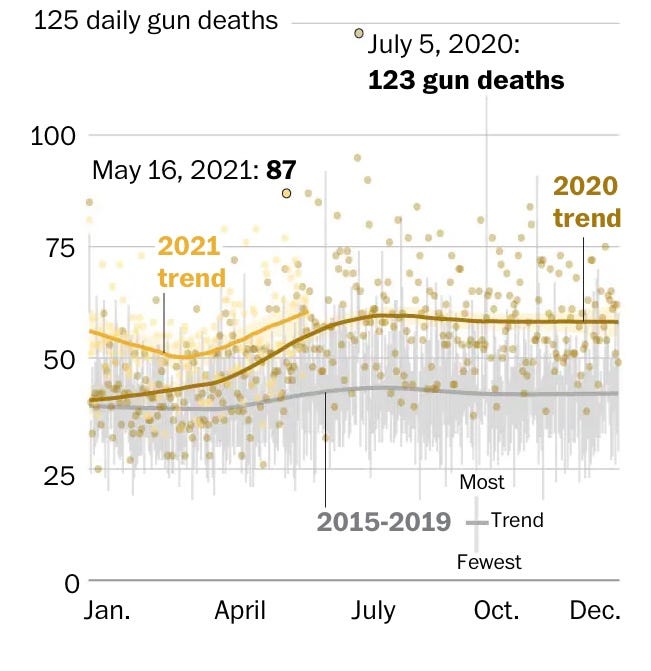

“Through the first five months of 2021, gunfire killed more than 8,100 people in the United States, about 54 lives lost per day, according to a Washington Post analysis of data from the Gun Violence Archive, a nonprofit research organization. That’s 14 more deaths per day than the average toll during the same period of the previous six years.”

The article included the following graph:

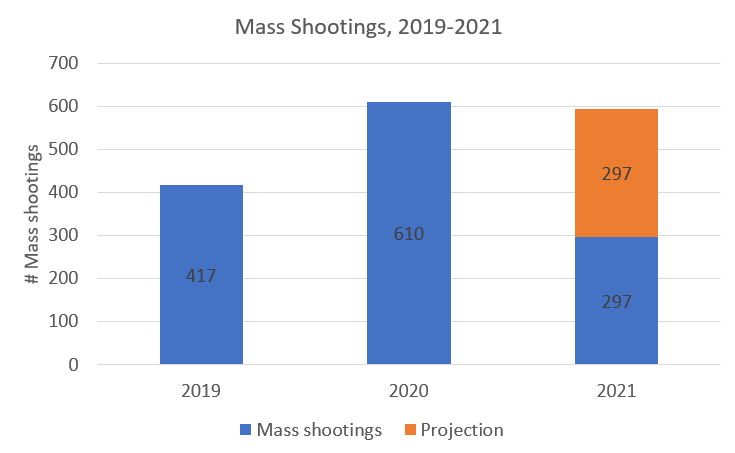

However, there’s a major mistake with this analysis. GVA changed their methodology in 2019 when they increased the number of sources in their surveillance system from 2,500 to 7,500. So, naturally, there will be more firearm deaths. In other words, comparing 2019-2021 numbers to pre-2019 is just not valid. It’s comparing apples to oranges.

We can really only compare 2019-2021 numbers. When we do this, 2021 is just NOT projected to be the most gun violent year. It’s on a trajectory to be more than 2019, but not more than 2020.

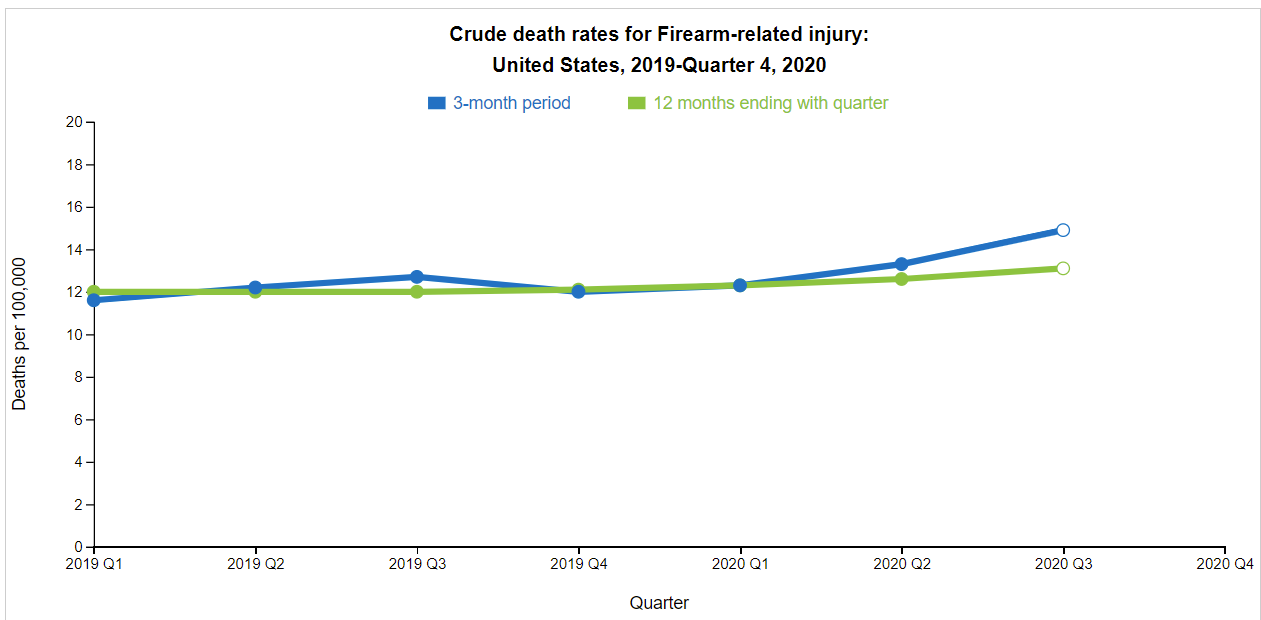

The second data source is, interestingly, from the National Center for Health Statistics, an arm of CDC. (The CDC has a rocky past with firearm research. Read my previous post here). This team tracks all types of injuries and deaths. Buried within the data is firearm-related deaths. In 2020, there was an uptick in firearm related deaths. And this uptick is statistically significant, which means it’s a true effect (not just something due to randomness). Unfortunately, this data is delayed, so we don’t have 2021 yet.

Bottom Line:

I don’t agree that 2021 is the “deadliest gun violence year in decades”. At least that’s not what the data tells us yet.

BUT, this doesn’t mean we don’t have a major problem in the United States. Another headline I saw was “we are about to have a pandemic of gun violence”. Sorry to break it to you… We already have a pandemic of gun violence!! We don’t need to wait for the “deadliest year” to talk about this. We need to find solutions. Now. Especially in a data-driven, evidence based manner.

Love, Dr. Katelyn Jetelina (YLE)

I have a question. Does the data support legislation as a effective method to control gun violence?

Why I ask this...

Currently I live in San Jose, California. Recently we had a workplace shooting. It was well thought out, planned, and executed almost perfectly except for the failed attempt to burn his house down.

In the house were high capacity firearms and magazines which are illegal in California. If they're illegal, how did he get them? He couldn't have acted alone. There's a paper trail somewhere. Why didn't the current laws prevent this tragedy?

And so I ask again, do gun laws work?

This is not an opinion carefully disguised as a question. I would really like to know what the data supports.