9 ways to spot falsehoods

Whether it's vaccines or elections, it's all the same motivations and tactics

It’s an incredibly difficult time to consume information. Whether it’s vaccines or elections, we have entered an era where it’s impossible to avoid falsehoods online. Social media posts from AI or well-coordinated, deliberate foreign (or domestic) disinformation campaigns look almost identical to legitimate concerns and questions, making it very difficult to discern the two. This has created chaos online, especially during highly consequential times—whether it’s a hurricane, elections, or a pandemic.

So what should we do?

Social scientists actually don’t know what works best against online falsehoods, yet. There are many theories, but we are flying the plane as we build it.

One evidence-based strategy is “pre-bunking.” This differs from combating each claim (“debunking”) or telling people what they need to believe. Pre-bunking prepares people to identify unwanted persuasion attempts regardless of the claim or topic. The idea is to build resilience by explaining the tactics and fallacies used so that people are equipped regardless of the topic.

A hot off-the-press study showed that pre-bunking election fraud messages for the 2024 U.S. general election decreased belief in election rumors for Democrats and Republicans alike.

More and more resources are coming out to teach people how to recognize tactics and fallacies so they feel well-equipped to navigate the information landscape. Examples are:

Games, like GoViral, teach people how information is manipulated.

Creative videos, like those by Truth Labs for Education, educate viewers on different tactics, like scapegoating.

9 ways this looks in practice

Of course, learning about a concept can be different than actually doing it in the wild.

One of my favorite journalists, Isaac Saul, writes the newsletter Tangle, which summarizes arguments from across the political spectrum and debunk a lot of rumors online. Saul recently asked his readers to anticipate the noise in the coming weeks. I was struck by how his lessons from the political space match those I have learned from the public health space.

Here are 9 tips that help us sift through the noise. They may be useful for you, too.

Basic sniff test. If vaccines are causing hundreds of thousands of deaths, wouldn’t we have overwhelmed morgues? If election workers were unloading trash cans full of ballots they forged at an election center, would they dump them out in front of a security camera? More often than not, these allegations don’t pass a basic sniff test. Pause and think before you share.

Follow the money. Most people don’t just spread lies for fun. They are doing it for one of two reasons: 1) political motivation, or 2) making a profit. If someone has created a movie that “proves” election fraud happened, but you have to pay $19 to view it, red flags should be going up everywhere. If a podcast talks about the benefits of supplements but then sells those same supplements thereafter, you should consider whether those two things are linked.

Ask follow-up questions. If someone makes a bold claim online, ask them to explain it. They’ll often respond with statements like “Democrats are stealing the 2024 election. We all know it.” Or “hydroxychloroquine obviously stops Covid-19 infections.” Ask them how they know it. Once you do, you’ll have evidence to analyze.

Find a second source. There are a lot of legitimate-looking news websites that are actually just organizations masking as something else. In politics, they exist on the left and right. In health, they are usually trying to sell something. These websites are typically shared on social media to go viral and get clicks. If you can only find a claim made by one source, there is a good chance something is fishy. See if it’s being confirmed in a more reputable news outlet.

Do two minutes of targeted research. If we see a claim, plug it into a search engine like Google or DuckDuckGo. This is a simple way to stress-test claims: look for the counter-evidence and see if someone else has already provided a better explanation.

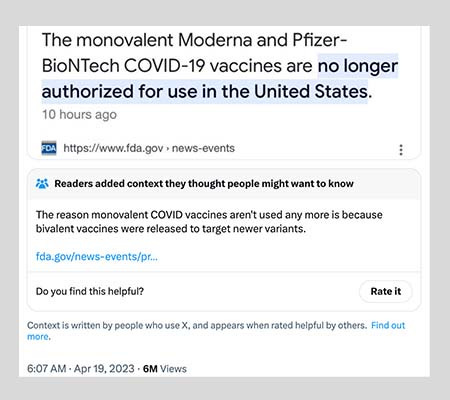

Read the comments and replies. If a claim is being shared, there is often a space for people to reply or comment. The replies and comments usually contain dissenting voices. (There’s always some crazy replies, too.) We always read the comments and replies for more information and gather other insights to help evaluate the claim. A recent study also showed that 97.5% of community notes on X were accurate for Covid-19 vaccines. We’ve found they can provide refreshing nuance in topics beyond vaccines, too; however, the community notes are often too late—the rumor has already spread.

Consult the experts. We know that’s corny to say, but it’s still important. Election experts are good sources. Most Americans have never worked as secretaries of state, poll workers, county recorders, auditors, investigators, or in other roles that give them unique insights into how elections are run. When you don’t have that experience, you can be convinced that regular, innocuous election activity is actually suspicious or dangerous. This is more challenging in the public health space, as some of the most prominent disinformation dozen have MDs behind their name. It’s okay to consult an expert’s opinion and, ideally, many opinions.

If a claim instantly sparks rage, take a step back. Strong emotions can temporarily blind us from thinking critically, causing us to accept something not because it makes sense but because it makes us mad. Social media platforms are optimized for engagement, meaning that sensational or emotionally charged content gets the most attention.

Maintain skepticism. More than anything else, rules 1–8 only work if you maintain a modicum of skepticism while navigating the information ecosystem we are operating in. That’s especially important if the information you are encountering reaffirms your worldview. More than anything else, do your best not to be gullible; don’t believe in dramatic or jaw-dropping claims without trying to follow these steps.

Bottom line

We are in a new information landscape, one that has immense benefits but also serious consequences. To adapt to the dense jungle of our information ecosystem, we must become responsible information consumers in ways we’ve never had to before. It’s hard but desperately needed for our health and our democracy.

Stay steady out there.

Love, YLE and IS

Isaac Saul is a politics reporter who grew up in Bucks County, Pennsylvania, one of the most politically divided counties in America. He founded Tangle, an independent, nonpartisan, subscriber-supported newsletter read by over 150,000 people, including conservatives, liberals, independents, and those who don’t identify with any political tribe. If you want to check out how they cover politics, I highly recommend his newsletter Tangle.

Your Local Epidemiologist (YLE) is founded and operated by Dr. Katelyn Jetelina, MPH PhD—an epidemiologist, wife, and mom of two little girls. YLE reaches more than 280,000 people in over 132 countries and has a team of 11 whose main goal is to “translate” the ever-evolving public health science so that people will be well-equipped to make evidence-based decisions. This newsletter is free to everyone, thanks to the generous support of fellow YLE community members. To support the effort, subscribe or upgrade below:

Excellent post. Thank you.

I think the problem is that the people who most need this information are least likely to read it, and if they ddo read it, are least likely to follow it. I think to address this provlem, it needs to be part of our early education system.

This is terrific advice. I particularly appreciated point 9, “maintain skepticism,” and within it, this: “That’s especially important if the information you are encountering reaffirms your worldview.” None of us are immune. Thinking independently is really hard work, but also immensely rewarding.