There’s no question that rapid antigen (Ag) testing is limited right now due to high demand: stores are sold out, health departments are prioritizing based on need, and online orders are delayed. While this shows that the U.S. government did not adequately prepare for Omicron, it also shows that people are finally leveraging one of the most under-utilized tools of the pandemic.

Mixed messages

But there’s still confusion about Ag test reliability in the wake of Omicron. And rightfully so, given the mixed messages over the past two months. Rapid testing stories are in the news and lighting up Twitter daily. In some stories, rapid tests are heroes, sparing elderly relatives from ill fated gatherings. In others, they are villains, accused of providing a false sense of security.

It’s been difficult to follow, but the big scientific developments have been:

Nov 27: Private companies, like Abbott and Quidel, evaluated their antigen tests using computer predictions and reported that they did not anticipate any impact on rapid test performance. These companies noted ongoing lab and clinical studies to verify their predictions.

Dec 17: UK corroborated this data in mid-December by analyzing 5 test brands used in the UK. They concluded that the mutations in Omicron “do not affect performance in the laboratory setting” and noted that clinical studies are underway to close the gap between lab and real-world.

Dec 27: CDC updated its isolation guidance and excluded testing parameters because “they didn’t work”

Dec 28: FDA released a broad statement stating: “Early data suggests that antigen tests do detect the omicron variant but may have reduced sensitivity.” and “It is important to note that these laboratory data are not a replacement for clinical study evaluations using patient samples with live virus, which are ongoing.”

These events ignited a lot of confusion among the public about what to make of rapid testing. To understand what’s going on, it’s important to tease apart analytical performance (how the tests perform in the lab, with ideal samples) and real-world performance (how the tests perform in patients). And, ultimately, what it means for you at home.

Analytical Performance

All evidence has shown rapid Ag tests can physically detect Omicron. In other words, when the antigen test is presented with the same amount of virus for the same amount of time, Ag tests perform roughly as well for Delta compared to Omicron (though one pre-print study reported slightly lower sensitivity with lab samples). That said, every brand of rapid test is unique, and needs to be rigorously re-evaluated. In the U.S. alone, there are dozens of options.

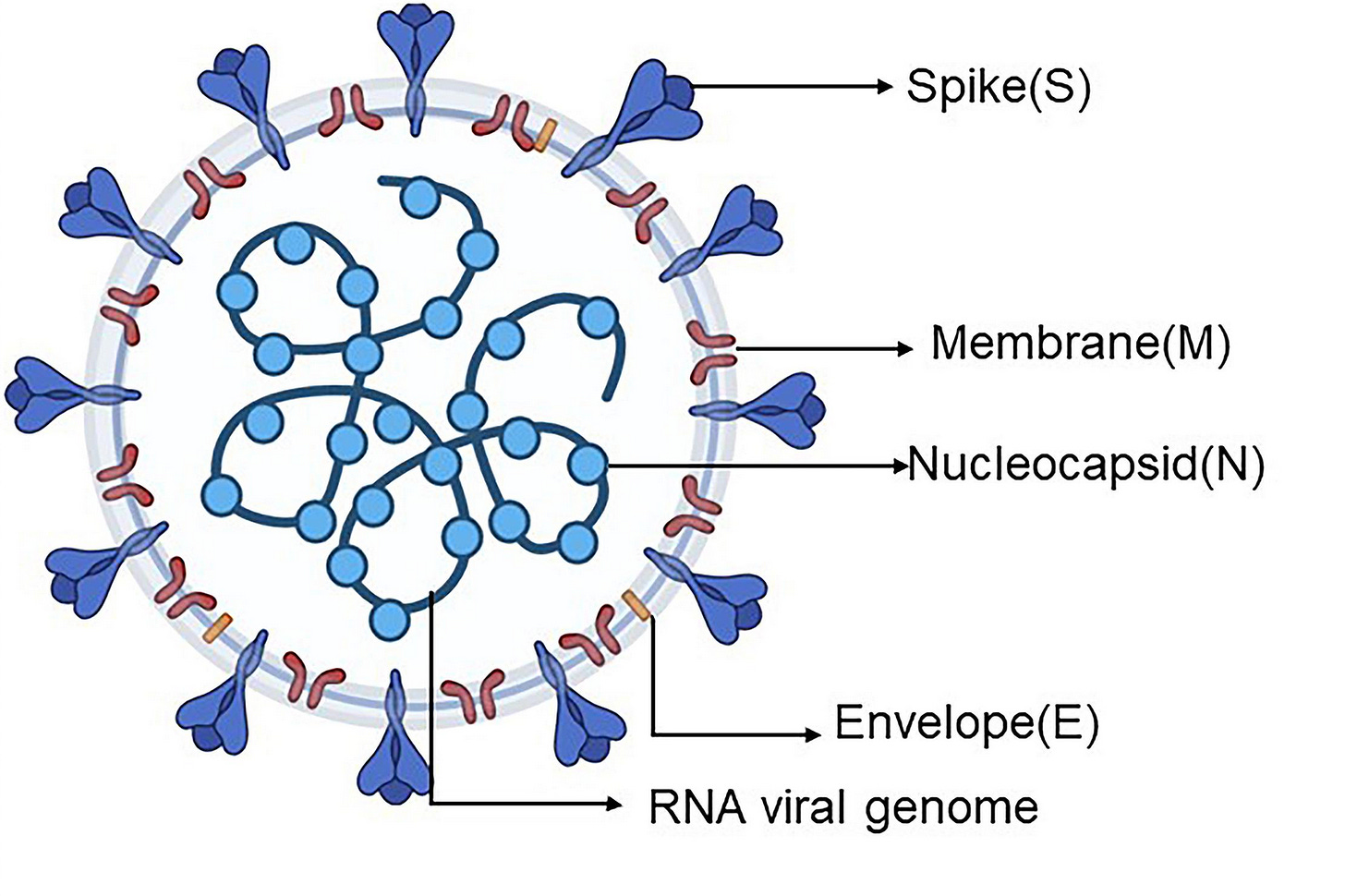

Antigen tests continue to work with Omicron because they target a fairly stable part of the virus called the nucleocapsid or N-protein. Unlike the highly mutated spike protein, Omicron has only 4 mutations in the N protein. Fortunately, none of these changes seem to alter the tiny part that rapid antigen tests detect. This is fantastic news because it means that we still have a tool to help calm the Omicron storm.

So, we know that rapid tests can find Omicron if we spoon feed virus to them in a lab. What about in the real world?

Real World Performance

We don’t know how well rapid tests detect Omicron in the real world because there aren’t any published, real-world studies. All we have to go on is reassuring studies with lab samples, a cautious statement from the FDA, and a slew of anecdotes and hypotheses.

We’ve discussed the reassuring lab studies above. Let’s touch on the FDA statement: “Rapid tests do detect Omicron but may have reduced sensitivity”. What does this mean and how can this be given the discussion above?

Sensitivity is the ability for a diagnostic test, like a rapid Ag test, to have a positive test result in subjects with the disease. So, in other words, this is the probability that someone is positive given that they have COVID19. The FDA stated that this probability (or sensitivity) is reduced with Omicron. The implication is that there could be more false negatives when testing for Omicron than other variants.

The FDA did not release any data to support this statement. They did, however, mention that tests with killed virus showed no difference in performance, but tests with known amounts of live virus showed lower sensitivity. This disconnect between killed and live virus samples suggests that the highly infectious nature of Omicron may pose a challenge to testing—if it becomes contagious at lower doses, it’s easier to miss.

The real world performance of rapid tests is also impacted by whether we are looking in the right place, at the right time. If the nose is not an early replication site for Omicron, then rapid tests that swab the nose won’t do as well - not because of a technical failure, but because the virus isn’t there yet.

Indeed, anecdotal evidence suggests that this may be happening with Omicron, with citizen scientists on Twitter reporting better luck with throat swabs than nasal swabs. Similarly, a pre-print found that saliva swabs are better than nasal swabs for early Omicron detection (by PCR) and another preliminary study found that Omicron is better at replicating in the bronchus (compared to the lungs).

What does this all mean?

Antigen tests are not perfect but they are still a valuable tool… for the question we (the public) want answered. Right now a lot of people just need to know one thing: Am I infectious and therefore need to isolate? This is very different from the question that clinicians, hospitalists, and scientists want to know: Does someone have any level of COVID19 virus in the body?

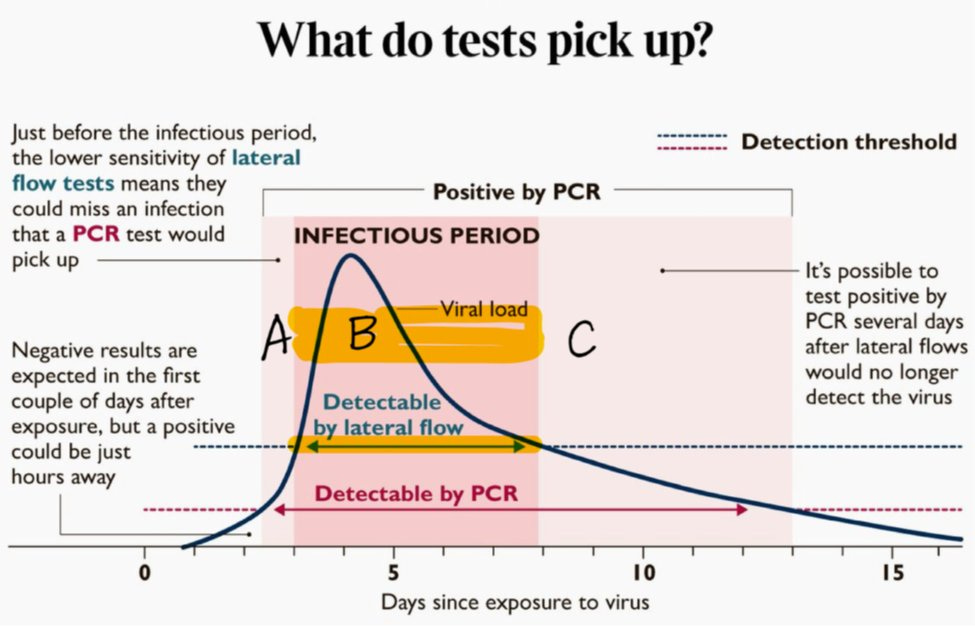

Because these are different questions, we need different tools. Rapid Ag tests answer the first question by detecting very high levels of virus, which turn the test positive. People are only contagious once they reach a certain threshold of virus. So, by default, catching high levels of virus will result in capturing whether someone is contagious. On the other hand, PCR tests are very effective at detecting the presence of very low levels of a virus. Importantly, the threshold in which PCR tests can detect virus is below the level of contagiousness. So, people can stay positive with a PCR for a long time (some documented cases show up to 60 days) but not be contagious. With an Ag test, though, that person would be positive for a much shorter duration and, more or less, while they are contagious.

Notably, this figure was made pre-Omicron, and it seems that there might be a slight shift with Omicron, such that symptoms, and possibly contagiousness, could begin before the first positive rapid test, due to the virus elsewhere in the body. Soon, we’ll no doubt see real-world studies that illuminate the grey area in those first few days of infection.

The next time you read about antigen test performance, consider the question being asked. Are we talking about flagging infectious cases or simply detecting any amount of virus? When the FDA evaluates rapid tests, they typically focus on the latter. To do so, they compare Ag tests to the “gold standard”—PCR tests. Because PCR tests remain positive for much longer, we’re of course going to find a lot of people who are still positive on a PCR but negative on an Ag test. This makes Ag tests look like they are failing. But, in fact, they are, by and large, answering the question as we would hope: Am I infectious?

What should I do?

Rapid Ag tests can detect Omicron and they can, most of the time, tell you whether you’re contagious. The first couple days after exposure or symptoms, they may not work as well. To counter this, here are four tips:

Wait. If you have symptoms or were exposed it’s important to isolate and wait a day or two to use an antigen test. This will ensure fewer false negatives.

Throat swab. Swab the throat and the nose to better detect Omicron. The UK has actually recommended this method since May 2020 for many of its tests (see instructions below). Here is their YouTube video. Avoid swabbing your throat after eating/drinking anything acidic — like coffee, soda, or fruit juices — as this could produce a false positive. Also avoid brushing your teeth or using mouthwash before a throat swab too as this could lead to a false negative.

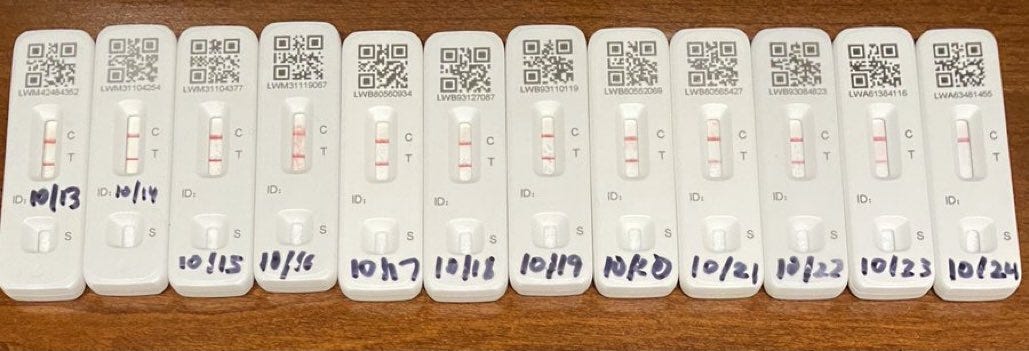

Line. Pay attention to the intensity of the positive line. If the line is very, very dark, this means you have a lot of virus and are infectious and a risk to your family and community. If the line is very faint, you could be in the beginning or the end of the contagious period. This is why it’s important to have a second test 24 or 48 hours after seeing a faint line to see if you’re still positive. This will give you an idea of whether you’re in the beginning or the end. Below is a display of rapid antigen tests over 11 days from my dear colleague in the UK (before Omicron). You can see that the second red line (indicating a positive test) gets very dark and then lighter and lighter until the test is negative.

Retest. A single negative rapid test can’t reliably rule out COVID-19, because it may be that you tested too early, and that the answer will change in a few hours, or a few days. If you think you probably have COVID, but the test was negative, and you need a definite answer, test again in 1-2 days (and isolate as a precaution).

A plea

I’ve been shouting from the rooftops for two years about how we need to implement public health mitigation measures more, not less, and this includes testing. So, my advice at this time may come as a surprise to many: Do not test right now if it is optional. We are in dire need of tests.

Optional means that you’re asymptomatic and not seeing vulnerable people. Optional means you’re boosted and healthy. Optional means you can work from home. Optional means you’re conducting asymptomatic screening to go on vacation or because you’re returning from a concert.

We will get to a point where we can screen ourselves as often as possible to reduce community spread and protect those around us. And this is the intended public health solution: Break as many transmission chains as possible. But because of Omicron and lack of preparation, we find ourselves in an impossible situation where many, many people need tests and can’t get them. So save the tests for:

Medical treatment: In order to get an antiviral in a timely manner, people need to test, see a doctor, and get a prescription within 5 days to prevent severe disease. These people need tests right now.

Medically vulnerable: Vaccines, and particularly boosters, will keep a large amount of people out of hospitals, but elderly and immunocompromised, even if fully vaccinated, are still at risk of severe disease. They need to be able to detect infection early through access to tests.

Breaking transmission chains to vulnerable: Those that live with an immunocompromised family member or going to a nursing home that need to be sure to break the transmission chain before arriving.

Avoiding more disruptions: Others need tests to get back to their jobs for paychecks, or because they are essential workers and we rely on them to show up at car accidents or to work in the ICU. Kids also need to get back to school. We have consistently put them last, throughout the pandemic, and need to change that.

Bottom line: Antigen tests continue to be a fantastic tool in this pandemic and they work against Omicron. But please consider the bottleneck of testing until we increase our supply in the United States, and how this calls for “pandemic thriftiness.” I still have hope that, one day, the United States will be prepared for the next wave.

Love, YLE and Dr. Chana Davis

P.S. We found two cool databases that keep track of available rapid tests with stats and validation status. It seems early for Omicron but potentially useful soon: Here and here.

Dr. Chana Davis, PhD is a brilliant scientist in Canada whose expertise lies in genetics, biomarkers, and diagnostics. She helped make sense of all the scientific literature on COVID19 antigen tests. She can be found at @fueledbyscience on Facebook, Insta, and Twitter.

“Your Local Epidemiologist (YLE)” is written by Dr. Katelyn Jetelina, MPH PhD— an epidemiologist, biostatistician, professor, researcher, wife, and mom of two little girls. During the day she has a research lab and teaches graduate-level courses, but at night she writes this newsletter. Her main goal is to “translate” the ever-evolving public health science so that people will be well-equipped to make evidence-based decisions. This newsletter is free thanks to the generous support of fellow YLE community members. To support the effort, please subscribe here:

Your third subhead should be "real worLd performance." Your Local Editor (Also, thanks for this--it is extremely useful and actionable information.

What would you suggest for those of us who are "hypersymptomatic" due to underlying conditions, such as allergies or acid reflux? One reason I use rapid tests is to justify fibbing about the stuff I always have. It's really the only way I have to rationalize going into work. Otherwise I'm forced to make impossibly subjective assessments of whether my cough is or isn't "dry" or "worsening" or if my nose is runnier than "usual". If someone comes up with a cough-o-meter I'll be more than happy to give up taking rapid tests.