Si quiere leer la versión en español, pulse aquí.

Today, after 2 long years, antigen tests are finally available to Americans free of charge. (Actually, yesterday the system secretly went live. More than 900,000 got word and flooded the site in a few hours). Each household can order up to 4 tests on covidtests.gov. Or you can go on the USPS website and fill out a surprisingly easy government form (oxymoron, I know). You will not be charged for shipping, and they don’t even ask for a credit card number. The tests should show up in your mailbox 7-12 days later. (There are a number of health equity issues with all of this, but that’s for another post).

And we really need to better leverage antigen tests in our pandemic toolkit. They are one of the most underutilized tools and can help us “learn to live” with SARS-CoV-2 by breaking transmission chains across the nation.

In my last antigen test post, I presented evidence that antigen tests could physically detect Omicron (thanks to the N-protein), and lab studies could detect Omicron at the same viral levels as Delta. But lab studies are highly controlled environments and certainly not reflective of the “real world.” We desperately needed evidence in the community. Now we have five studies and each has a unique contribution to the puzzle we’re trying to put together: How well do antigen tests work?

Here is what they say.

Be careful with negatives in the beginning of infection

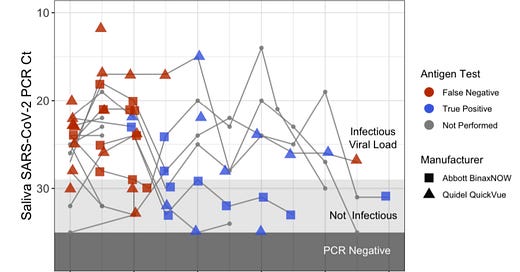

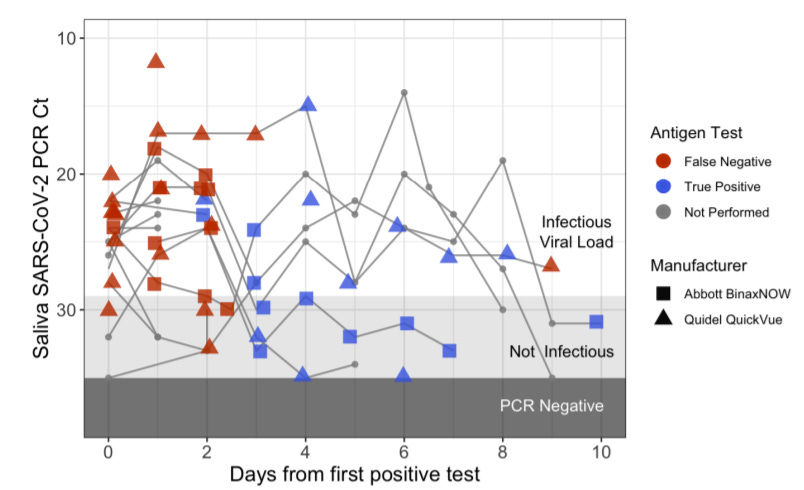

The first study followed 30 people in high-risk jobs from December 1 to December 31, 2021, during Omicron outbreaks at five workplaces in New York, NY, Los Angeles, CA, and San Francisco, CA. Everyone was fully vaccinated (boosted by choice) and was being tested daily. The scientists compared how well nasal antigen tests worked against saliva PCR tests. They found a few interesting patterns:

The average time from first positive PCR to first antigen positive was 3 days

Peak viral load was 1-2 days earlier in saliva than the nose

All individuals developed symptoms within two days of the first positive saliva PCR test

It’s possible to be contagious yet have a negative rapid test. Four of the 30 people in this study spread COVID19 between negative rapid tests.

It’s important to note that this study primarily compared nasal antigen tests to saliva PCR tests. So, are these findings because antigen tests aren’t as great in the beginning of infection OR because of the location which was swabbed? It seems like the location of the swab is a big part of the answer. Five people in this study also had a nasal PCR. The saliva PCRs consistently had stronger signals (lower Ct values) than the nasal PCRs in the first few days of infection.

This study tells us that we need to be super careful when using rapid tests in the first few days of exposure or infection. To get the most from your rapid test, wait at least 48 hours after symptoms and 5 days after exposure before taking an antigen test. If you’re negative, test again 24 hours thereafter. You can certainly test sooner, but any negative results will be unreliable. A positive antigen test result, on the other hand, is very reliable right now, especially after exposure or with symptoms.

(For the record, the CDC rapid testing website FAQ section advises testing 5 days after close contact or as soon as you begin feeling symptoms. We think it’s better to wait a bit longer after symptoms.)

Antigen tests work really well thereafter

The second “real world” study compared nasal antigen tests with nasal PCR tests among 731 people in San Francisco from January 3-4, 2022. The scientists evaluated how well the BinaxNOW rapid antigen tests performed compared to PCR at a community-based testing site. What did they find?

Overall, 296 of 731 (40.5%) tested positive on the PCR.

Among people with a positive PCR with no symptoms (59 people), antigen tests detected 53 positive. This equated to a sensitivity of 89.8% .

Among people with a positive PCR who were symptomatic, the sensitivity of antigen tests was 97.6%.

As expected, the higher the viral load, the more accurate the antigen test.

The tests were just as accurate among those under 13 years of age compared to those older than 13.

The tests performed similarly regardless of vaccination status.

The likelihood of a false positive was very small (432 of 435 PCR negatives were correctly identified as negative by rapid tests).

This preprint study was updated a few days ago. They added data from a pilot study of cheek swabs among 75 people, both by PCR and by rapid antigen test. This is what they found:

Cheek swabs performed far worse than nasal swabs.

Among 46 PCR positives, 22 were positive by antigen in the nose and only 2 were positive from the cheek. These results are disappointing, yet important to know.

In all, this study reinforces the notion that rapid tests are failing in the first few days not because of technical issues, but because Omicron is changing disease biology. It seems there is now a lag between symptoms, contagiousness and viral explosion in the nose. When the virus does take hold in the nose, rapid tests can usually find it, even without symptoms.

You’re infectious for longer than 5 days

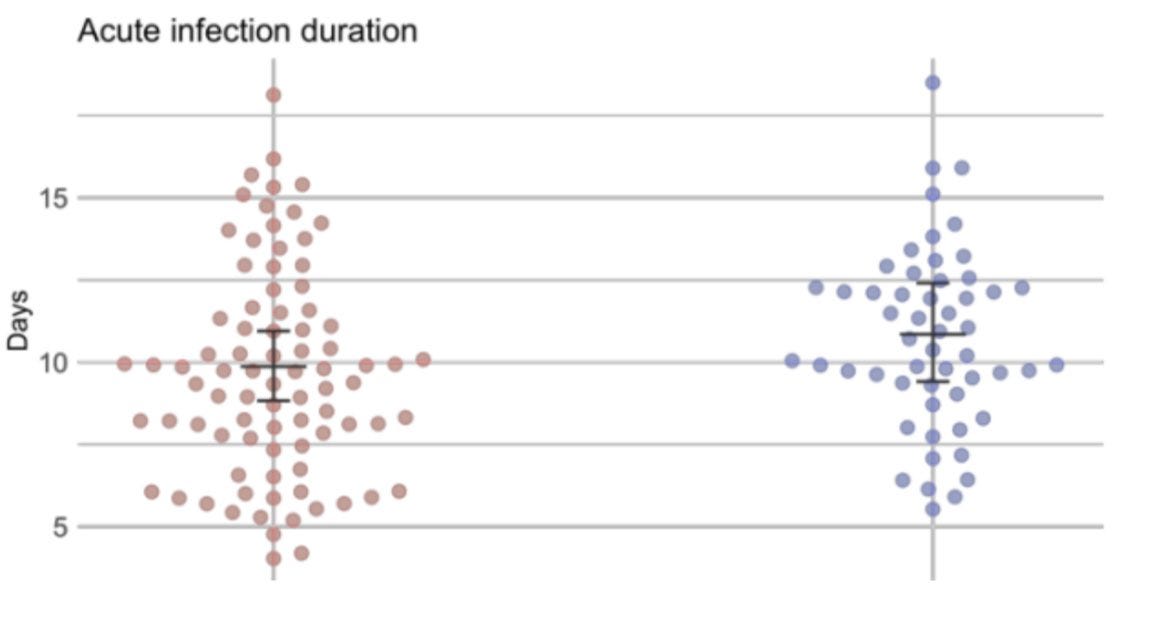

The third study evaluated how Omicron infection was (or was not) different from Delta infection among National Basketball Association players—a highly vaccinated population that is tested daily. Specifically, scientists evaluated 97 tests confirmed from the Omicron variant and 107 from the Delta variant and compared how the tests varied on a myriad of factors (viral load, length of infection, etc.). Samples were all collected using dual swabs (nose and throat) and evaluated with PCR. What did they find?

Omicron infection lasted, on average, 10 days. This is comparable to Delta infections which lasted, on average, 11 days.

Many people cleared the virus faster and others clear the virus much slower.

Roughly 50% of people still had a high viral levels at Day 5 (meaning they were likely infectious).

Together the results suggest a broad range of an infectious period, which is all the more reason to use a rapid antigen test-to-exit strategy in the United States.

The U.K. agrees

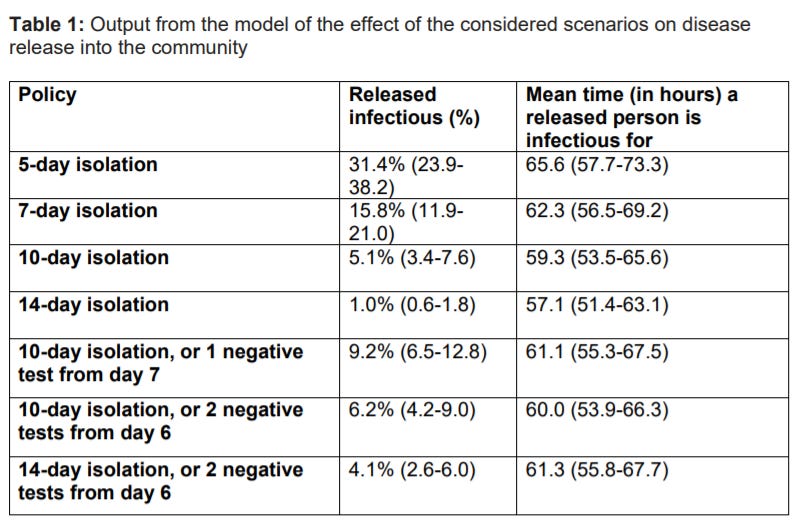

A separate modeling study in the U.K. estimated the impact of leveraging antigen tests to end isolation (something the CDC is not recommending). Specifically, the scientists were interested in how many people would be infectious given different policy recommendations. What did they find?

During a 5-day isolation period (and not using an antigen test), there is a 1 in 3 (31%) chance you’re still infectious.

During a 7-day isolation period (and not using an antigen test), there is a 1 in 6 chance you’re still infectious.

If you use an antigen test on Day 7 of isolation and it’s negative, there is less than a 1 in 10 chance you’re still infectious. This is the same odds as if you isolated for 10 days without testing.

In England, the isolation policy was updated again this week: “It is now possible to end self-isolation after 5 full days if you have 2 negative LFD tests taken on consecutive days. The first LFD test should not be taken before the fifth day after your symptoms started (or the day your test was taken if you did not have symptoms).”

Viral load isn’t the same thing as infectious load, though

All the previous studies (except the U.K. report) analyzed “viral load” or the number of virus particles because it’s the easiest to measure for a quick turnaround study. However, and importantly, the number of viral particles does not equal the number of infectious particles. And the latter is what we are truly interested to answer: Are we infectious?

The final “real world” study was conducted in Switzerland among 384 symptomatic individuals at a community testing center, who were tested during the first five days of symptoms. The goal was to examine the relationship between viral load (measured by PCR) and contagiousness (measured by lab experiments). What did they find?

The precise viral level by PCR was not a great predictor of infectiousness—it was a modest 31% correlation. This is okay, but certainly not fantastic.

The number of infectious particles was lower among vaccinated compared to unvaccinated people.

Omicron was not substantially different from Delta, either in terms of viral load or contagiousness. In other words, we need to look elsewhere to understand Omicron’s mysteriously high contagiousness.

This study did not include rapid antigen tests, but given that we are seeing considerable infectiousness at viral levels lower than what rapid tests pick up, it’s best to assume that a positive rapid test means you are contagious, no matter what testing day you’re on.

Bottom line: Use antigen tests. Use antigen tests. Use antigen tests. Do so wisely.

Be aware of false negatives in the early stages of infection, and know that it can take several days after symptoms for the virus to take hold in your nose. Once you reach the tipping point, rapid tests are a reliable way to detect and monitor your infection.

Trust your positive test during the Omicron wave.

If at all possible, do not leave isolation without testing (I don’t care what the CDC says). If you can’t access tests, assume you are contagious for 10 days, and act accordingly.

Love, YLE and Dr. Chana Davis

Dr. Chana Davis, PhD, is a brilliant scientist in Canada whose expertise lies in genetics, biomarkers, and diagnostics. She helped make sense of all the scientific literature on COVID19 antigen tests. She can be found at @fueledbyscience on Facebook, Insta, and Twitter. Chana is also a Nerdy Girl at Dear Pandemic (Substack, Facebook, Website).

“Your Local Epidemiologist (YLE)” is written by Dr. Katelyn Jetelina, MPH PhD—an epidemiologist, biostatistician, professor, researcher, wife, and mom of two little girls. During the day she has a research lab and teaches graduate-level courses, but at night she writes this newsletter. Her main goal is to “translate” the ever-evolving public health science so that people will be well equipped to make evidence-based decisions. This newsletter is free thanks to the generous support of fellow YLE community members. To support the effort, please subscribe here:

"It’s possible to be contagious yet have a negative rapid test. Four of the 30 people in this study spread COVID19 between negative rapid tests." - How, if at all, would you change your recommendations around using rapid tests before you see elderly or at risk people? I think we'd hoped that a negative rapid test meant that at the very least you weren't (very) contagious and you could have some comfort from that before seeing at risk family/friends. This seems to contradict that and is so disheartening.

Is there any evidence to show that fully vaccinated and boosted (if relevant) are taking longer to test positive on rapid antigen tests even though they end up truly being covid positive? I know of 4 instances now among two different families where individuals continuously tested negative on serial testing but ultimately were positive on days 7 - 12 after exposure. Given how virulent omicron is reported to be and the replication of it in a human system being more rapid, is this just a fluke or do vaccines play a role in trying to shut the incoming virus down but ultimately succumb to its high replication rate? For the record, all illness in these individuals was mild and short-lived.