We are clearly in the middle of an infection surge in the U.S. Hospitalizations are increasing but not reflecting case acceleration, and deaths are nearing pandemic lows. The individual risk of severe disease continues to decline thanks to immunity and treatments.

This changing dynamic has sparked an intense tug-of-war among scientists, leaders, and the public—a push towards “normalcy” from some and push back towards “urgency” from others. Where one lands on this spectrum is centered around the answer to one question: Are we in a public health emergency?

Challenging answer

This debate will ultimately decide if, when, and how we differentiate a country-wide emergency (epidemic) from a manageable situation (a middle phase) until we reach a predictable, static state of disease (endemic). Essentially we’re collectively deciding where we place SARS-CoV-2 in our repertoire of threats. This isn’t something the U.S. has navigated in the modern day with a novel respiratory virus.

In reality, our collective answer isn’t purely epidemiological, but also physiological, cultural, political, and moral. I think this is difficult, particularly in the U.S., for four reasons:

No goal. The CDC defines an epidemic as “an increase, often sudden, in the number of cases of a disease above what is normally expected in that population in that area.” For the past two years, there’s no doubt we experienced a country-wide epidemic—it was novel and, by definition, above normally expected—causing a public health disaster of over 1 million deaths. Because we know SARS-CoV-2 will be with us in the foreseeable future, what is now an “unexpected increase” in disease? For example, U.S. deaths are starting to plummet which looks relatively great, but how low is low enough?

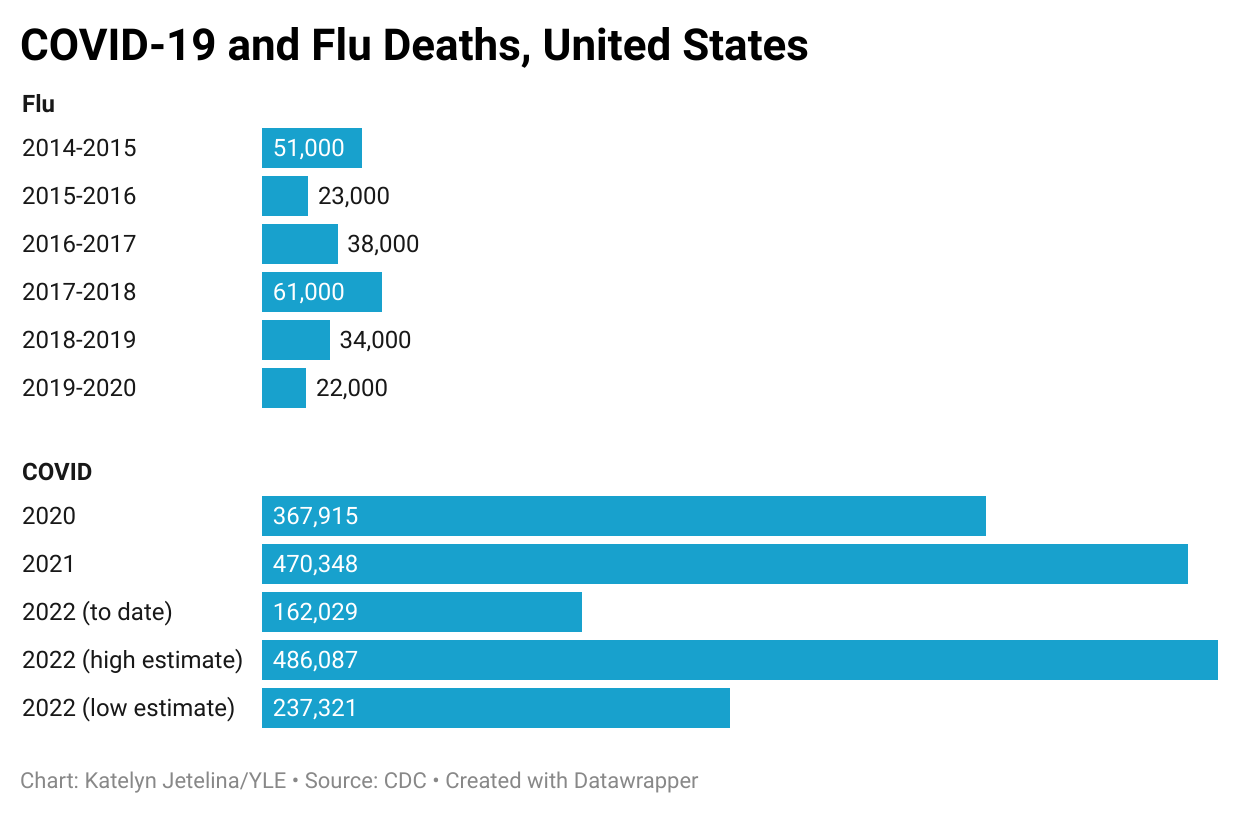

One group suggested that an “acceptable” endemic level of SARS-CoV-2 would be to keep peak COVID-19 deaths in a surge below the peak of a bad flu season. As I charted below, we are far from the flu threshold. The worst flu season was in 2017-2018 where 61,000 deaths were recorded. In the first 5 months of 2022, we already surpassed this number more than 2-fold. This lands SARS-CoV-2 as the third leading cause of death. Is this truly an “acceptable” level for the U.S.?

Unpredictability. If we are not in an epidemic, then we are floating in a weird middle-ground because we’re not in an endemic either. Transmission is not stable or predictable, the virus is changing quickly, and we have no idea what it will do next:

Will Omicron continue to mutate in a ladder-like fashion or will it mutate to an entirely different Variant of Concern and throw us for a loop, like Omicron did after Delta? We have no idea.

If we do get an Omicron-like event, when will it happen? We have models suggesting it will be in 1.5 years or 10 years. In other words, we have no idea.

Will the virus mutate to become less severe or more severe? Unfortunately, viruses mutate randomly. We don’t know the next move.

This means that if we’re not in an emergency today, we may be in one tomorrow. The dynamic nature of the virus is also changing the meaning of “emergency” over time. For example, during the Delta wave and before vaccines, the emergency was mortality. But during Omicron, the emergency was hospital capacity (and mortality). Some have argued that the next emergency is already in the works: morbidity due to long COVID. Our definition of an emergency will change, making it even more difficult for us to collectively define the “end” of an emergency.

Fatigue. In a series of polls, it’s clear that about half the country would like to move on from this virus. In one poll, 55% of voters think COVID-19 should be “treated as an endemic disease that will never fully go away” while 38% say it should be “treated as a public health emergency.” Pandemic fatigue is real. People are losing hope. And, individual-level risk is low, so the population-level threat feels distant. The collective, national-level psyche plays a huge role in defining our collective threshold of concern about SARS-CoV-2.

No safety net or trust. During the Omicron peak, Denmark boldly declared the emergency over. I was not surprised given their high vaccination rate, ability to track the virus with comprehensive data, and wide safety net of universal healthcare coverage, paid time off, etc. More than 90% of Danes approved ending the state of emergency, too. In Australia, public trust enabled them to dodge death until the vast majority of the population was vaccinated. But safety nets and trust are in short supply in the U.S. Because of this, the decision to end a public health emergency in the U.S. is particularly difficult, as it’s a question of leaving people behind and trusting institutions.

This is really important to get right

Practically speaking, defining an emergency is really important for funding and thus our capacity to fight. The current public health emergency declaration, for example, goes until July 15, 2022. The Biden Administration promised states 60 days notice before the declaration expires, which would have been two days ago. I would be very surprised if they let the emergency expire in the middle of a surge, but as I outlined above, the answer isn’t clear.

As the Kaiser Family Foundation clearly laid out, if the emergency declaration goes away, it will be a big deal. We will see changes in almost every aspect of this pandemic response as outlined below. Together it will be more difficult to fight the virus and easier to accept the current state of affairs as “normal.”

Concurrently, the White House is also trying to push two pandemic preparedness funding packages. These need to go through, but it’s unclear whether the public will prioritize pandemic preparedness if we’re not in an emergency (we tend to have short term memory loss). If pandemic preparedness is not funded, the U.S. public health system will continue the deadly and exhausting cycle of neglect and panic that we’ve experienced for decades. But is this reason alone sufficient to declare an emergency?

Bottom line

We are in a strange phase of the pandemic—caught somewhere between epidemic of emergency and endemic of manageable disease, determined by the push and pull of epidemiology, culture, politics, and psychology. We haven’t clearly defined our end goal, so it’s incredibly confusing to know what to think, who to listen to, or what to do. And we are tired of trying to figure it out.

We, as a nation, will ultimately decide what we accept from SARS-CoV-2 based on national-level decisions (Do we fund public health to improve data systems, discover the next generation of vaccines, and support testing for Medicaid and Medicare?), institutional-level decisions (Do businesses improve ventilation and filtration? Can we build trust with the public again?), and individual-level decisions (Do we use antigen tests to break transmission chains? Do we wear masks when surging? Do we get vaccinated?). Every day we unconsciously (or consciously) inch towards the collective answer. The decision is up to us.

Love, YLE

Pssst—this week we got more tools to help:

You can now order 8 more antigen tests to be delivered to your home. Go to the USPS website now.

The FDA approved age 5-11 boosters, but the CDC needs to approve. They meet Thursday and should approve it quickly thereafter. On June 8, 21, and 22, the FDA meets to discuss the under 5 vaccine.

The FDA approved a 3-in-1 Labcorp test that can detect COVID, the flu, and RSV. Specimens have to be mailed for testing (questioning broad feasibility), but this is a step in the right direction.

“Your Local Epidemiologist (YLE)” is written by Dr. Katelyn Jetelina, MPH PhD—an epidemiologist, biostatistician, wife, and mom of two little girls. During the day she works at a nonpartisan health policy think tank, and at night she writes this newsletter. Her main goal is to “translate” the ever-evolving public health science so that people will be well equipped to make evidence-based decisions. This newsletter is free thanks to the generous support of fellow YLE community members. To support the effort, please subscribe here:

It strikes me that there's another factor in play here: Do we as a society and as individuals care about working to prevent harm to others more at risk?

Our society tends to focus on the greatest good for the greatest number, especially of those we center - as opposed to preventing harm for those on the margins. We tend more so than other counties to be individualistic rather than focusing on the vulnerable.

From my point of view, people and government declaring this to already be endemic, dropping protections like masking or free tests, dropping funding, etc. are effectively saying to vulnerable people that "Your deaths are acceptable to us." Sometimes this is crass and obvious as a form of social homocide, other times it's more subtle as part of focusing on "normal" people and not thinking about others.

Granted that everyone will die someday, but for me a key question is whether society believes it is entitled to the deaths of those less fortunate so people can go to a movie?

This isn't a new issue, but rather one COVID has put into stark relief. COVID's effects have quite disproportionally harmed older people, poorer people, disabled people, minorities, etc. Declaring COVID "over" magnifies those harms.

Brilliant post! Now, if we could just get the two camps of scientists/ engineers to stop yelling at each other...

...it would help.

You are spot on that this is complicated!