On Monday WHO’s Emergency Committee gave official word that they voted to renew the Public Health Emergency of International Concern. They are likely teeing up for “the end” in 2023.

The U.S. is far more confident in “the end” of the national emergency. On Monday, the White House announced that they are ending it in mid-May.

An inflection point is clearly on the horizon, albeit with uncertainty. This leads to legitimate questions: Are we still in an emergency? What will the future hold? What happens next?

Are we still in an emergency?

There is no “level of disease” that defines a pandemic or emergency. Even if there was an objective metric, the reality is that this isn’t determined through epidemiology alone. Where we, as a society, place SARS-CoV-2 in our repertoire of threats is a collective decision—a psychological, cultural, and political decision. Every day we consciously (or subconsciously) decide how much risk and suffering we are willing to accept: How many people get the booster? How many people wear a mask? How many people order free antigen tests? How many deaths, and among whom, are we willing to accept?

This has sparked an intense tug-of-war among scientists, leaders, and the public throughout the pandemic: a push towards “normalcy” from some and push back towards “urgency” from others. All individuals and societies fit somewhere on this spectrum. And one’s position may (and perhaps should) change with time.

How did winter play out?

How we fared this winter gives us a good idea as to whether we are still in “emergency” phase in the U.S. We essentially had two tests:

How well did our immunity hold up against a constantly changing Omicron? According to varying hospitalization models from early fall, the 2022-2023 winter played out as a best case scenario for COVID-19. Even the best case scenario, though, led to a peak of 48,000 hospitalizations.

Could our hospital systems handle the stress of a novel virus on top of the “normal” respiratory viruses? We hadn’t previously seen the impact of all of them at the same time. In addition, health care workers are increasingly burnt out, and hospitals are increasingly understaffed. Given all of this, hospitals did okay this winter. Pediatricians were drowning, particularly because of a massive RSV wave. Emergency rooms were overcrowded with sickness. But a COVID-19 emergency declaration wouldn’t necessarily help with either of these. Hospitals were not overwhelmed with adults because of our immunity wall, and I’m increasingly convinced there was viral to viral interaction—in other words, we didn’t see all three viruses peak at the same time.

Given this, I agree that we are not in an emergency phase in the U.S. An emergency declaration was appropriate when we had rational hope that transmission could be interrupted on a population level and when we needed extreme measures to prevent collapse of healthcare systems. We are past this. Continuing the emergency would not be constructive given public sentiment and lack of funding anyway. As one epidemiologist told me, “If it’s always an emergency, nothing’s an emergency.”

What will the future hold?

If we end the emergency, it begs the question: What phase are we in?

I don’t believe we are in an endemic phase— a state of predictability. I think we are on our way, and COVID-19 will eventually fall into seasonal patterns. But this will likely take years.

Until then, we will be in an awkward space between pandemic and endemic. Epidemiologists don’t have an official word for this phase. WHO flu risk management people would probably call this the “transition” phase.

We will continue to see the virus ebb and flow—it will mutate, we will get waves, people will continue to miss work and daycare, and people will continue to be hospitalized and die, particularly those over 65 years and immunocompromised. The end of an emergency does not mean the end of disruption or suffering.

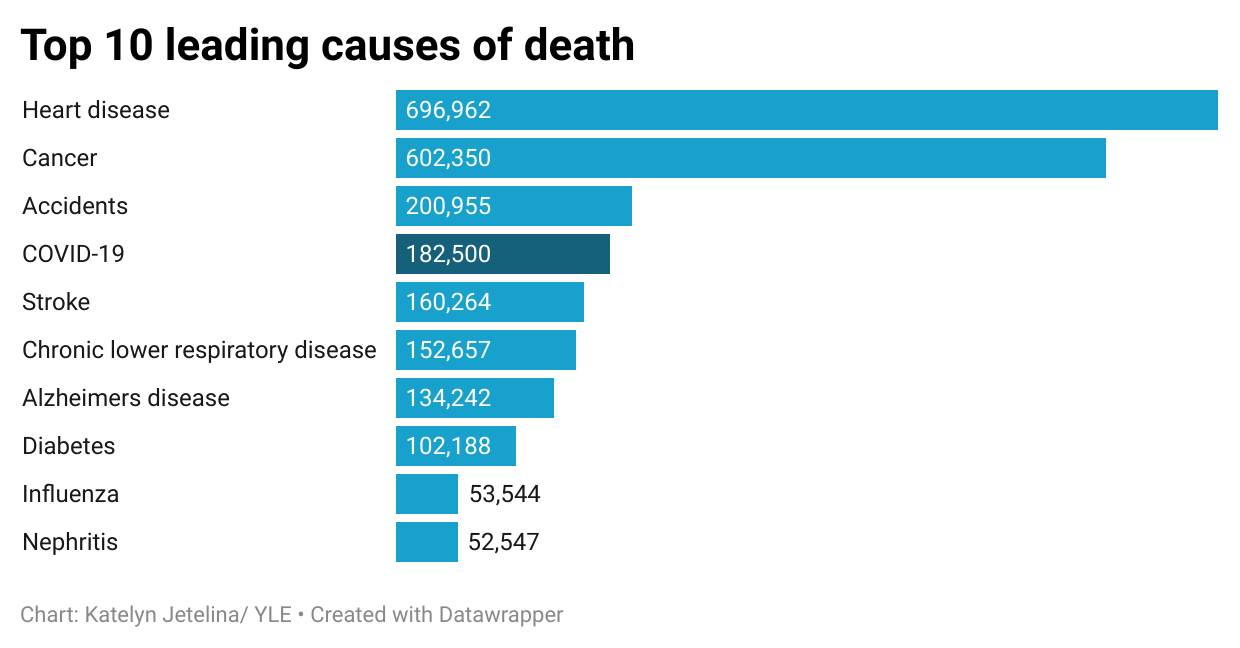

Today, roughly 500 Americans are dying each day from COVID-19. At this rate, SARS-CoV-2 will be the fourth leading cause of death in the U.S. in 2023—about triple the threat of influenza.

What happens next?

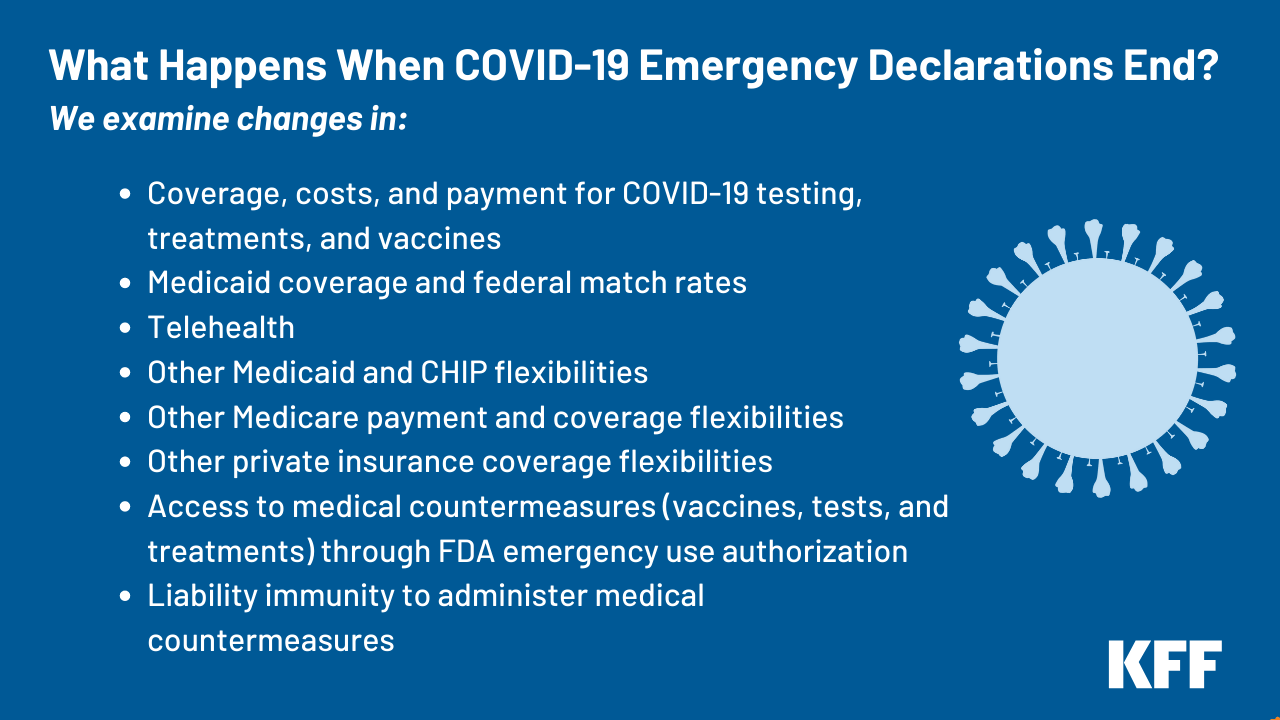

Unraveling the public health emergency may get messy. It will certainly take time (hence the 3 month lag time). The Kaiser Family Foundation outlined the implications nicely:

In addition:

This does not impact the Emergency Use Authorization of vaccines and therapeutics from the FDA. In other words, these will still be available.

HOWEVER, the ending of funding for testing and vaccines is a real cause for concern. Once our free supply is out, everything will be privatized. Pfizer announced its vaccine will cost $130 per dose. Insurance will have to cover it, like the flu vaccine. This will, no doubt, fuel deep inequities in the U.S. And it is part of a much larger, deeply flawed system of pharmaceutical profiteering that this country hasn’t got the ethical fortitude to address yet.

Our work is not done

Most importantly, the end of the emergency doesn’t mean our work is done. There is no infectious disease more insidious or with greater impact on global mortality, morbidity, and health care systems than COVID-19.

As individuals, we still need to get vaccinated. We still need to leverage antigen tests. We need to invest in better filtration and ventilation. We still need to protect the most vulnerable.

As public health officials, we must decide the minimum structure needed moving forward. Invest in wastewater monitoring. Continue to report hospitalizations (and get better at it). Commit to transparent and effective communication. Vaccine innovation is needed.

As a society, we MUST put real energy, innovation, and investment into repairing and strengthening our health and public health systems. The new normal cannot fall back to a pre-COVID normal. We must be bigger, better, and smarter. This means the very notion of for-profit healthcare needs to be fixed. In public health, we must figure out how to get out of the cycle of panic and neglect through preparation. We are LESS prepared for the next pandemic, given loss of trust, polarization, changing information echo-systems, and mis/disinformation.

Sadly, I’m starting to see denial and wishful thinking. I hope this changes as it will definitely not be another 100 years before the next pandemic emerges to grip the globe in a choke hold.

Bottom line

In the U.S., the end of the emergency is coming. I agree with this decision, but this certainly isn’t the end of COVID-19 or public health threats. In fact, this end is the beginning. We have our work cut out for us.

Love, YLE

“Your Local Epidemiologist (YLE)” is written by Dr. Katelyn Jetelina, MPH PhD—an epidemiologist, data scientist, wife, and mom of two little girls. During the day she works at a nonpartisan health policy think tank and is a senior scientific consultant to a number of organizations, including the CDC. At night she writes this newsletter. Her main goal is to “translate” the ever-evolving public health science so that people will be well equipped to make evidence-based decisions. This newsletter is free thanks to the generous support of fellow YLE community members. To support this effort, subscribe below:

You wrote : "Sadly, I’m starting to see denial and wishful thinking." Starting?? Personally, I think that's been happening for some time. No masks, "it's over", "I stopped thinking about the deaths". I do agree that we need to figure out a way to adjust to the fact that it's not going away, but as someone who is high risk, I just feel increasingly isolated and stigmatized. Apparently people who mask on planes are being harassed.

I always appreciate your approach to delivering serious information with a practical acknowledgement of what works for real humans and how we truly behave. But I think this piece (and much of the greater conversation about whether this is an "emergency") really overlooks the very real data about not just the Long Covid we've heard about—ongoing sequelae like fatigue, brain fog, etc—but the amplified cardiovascular risks, the damage to multiple organ systems, the long-term degradation ofthe immune system. I feel we can't look at the Covid picture as an acute illness that causes lots of disruptions and inconvenience. It has to be acknowledged that we're setting up literally all of society for increased long-term health problems, and that we're also rapidly accellerating those problems for those who are already immunocompromised and/or at higher risk. This goes WAY beyond it being annoying to have your kid home from daycare and is actually a *humanitarian* emergency.