Bite-sized Threats of Ticks

All you need to know, including yes, misinformation

Well, we are still in the dead middle of tick season. Does it seem like the season is getting longer? Or are you seeing more and more ticks around?

While there are nearly 900 species of ticks globally, and their reach is increasing, only a handful pose a risk to human health. Unfortunately, like anything, rumors about ticks—their spread, risk, and effective tools—are abundant on social media.

So, what’s the current state of affairs with ticks?

The geographic range of ticks is expanding.

Most tick species thrive in warmth, humidity, and lush spring vegetation, so ticks cluster based on habitat.

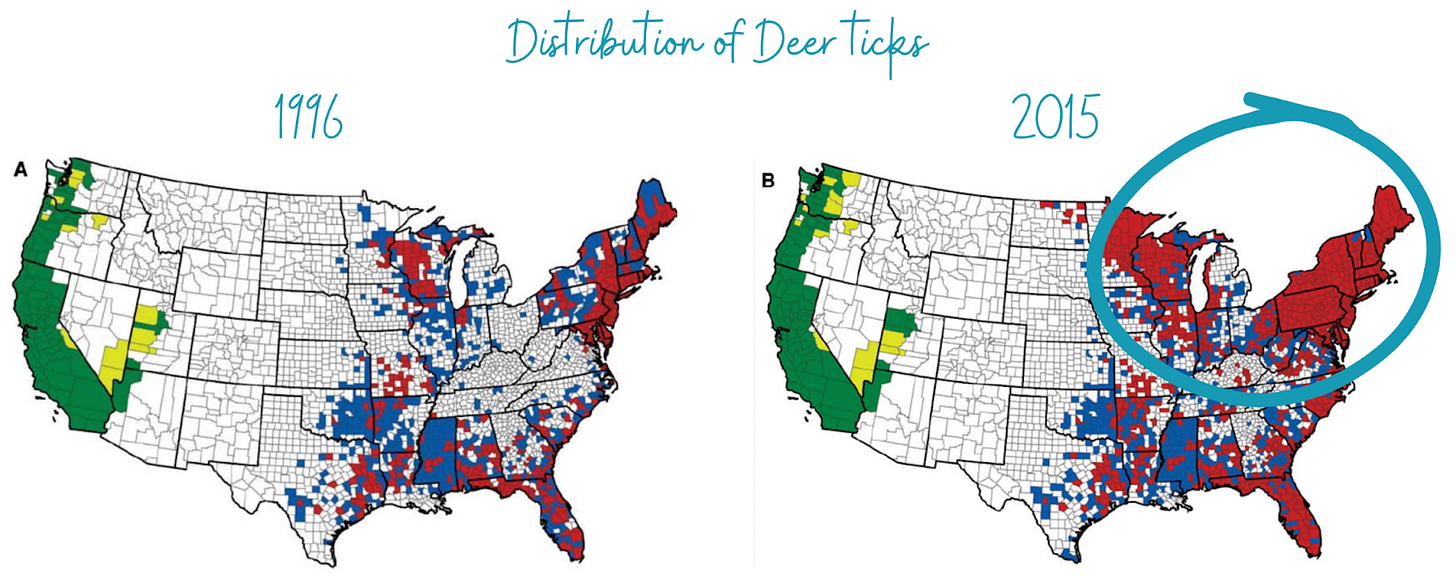

Over the years, the distribution of tick populations has grown. For example, the map below shows the reach of the black-legged (deer) tick in 1996 versus 2015, which shows expansion across the northeast. This tick can cause Lyme disease.

The Gulf Coast tick population expansion is shown below. This tick can cause Rickettsia parkeri rickettsiosis. The dark black line shows the distribution before 1996, but surveillance shows these ticks are moving North.

Why the increase in tick ranges?

A lot of reasons, including:

Increased interaction between humans and animals as a result of land development, human population growth, and proximity to backyard wildlife.

Less harsh winters mean more ticks survive overwintering. Ticks produce antifreeze, so the temperature must be below 10F for several days for ticks to die.

Increased surveillance of tick species that are of human and agricultural concern.

Ticks can transmit at least 20 diseases in the U.S.

The U.S. has ~20 tick-borne diseases (TBD). But not every tick you encounter will give you a disease. That’s because several things need to fall into place:

The right species of tick

The right pathogen inside the tick

The right bite (each pathogen has a minimum attachment time)

Immune system doesn’t clear it before it causes illness

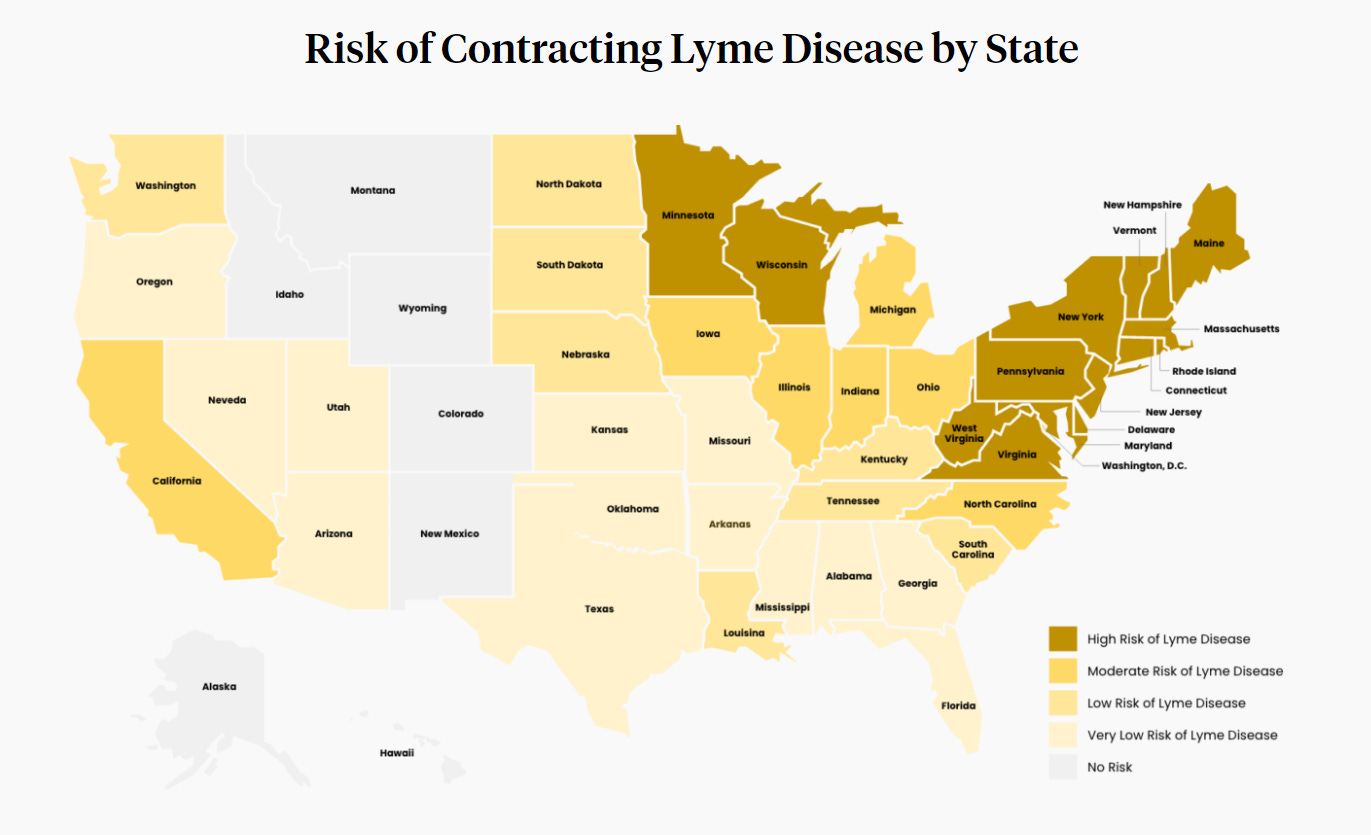

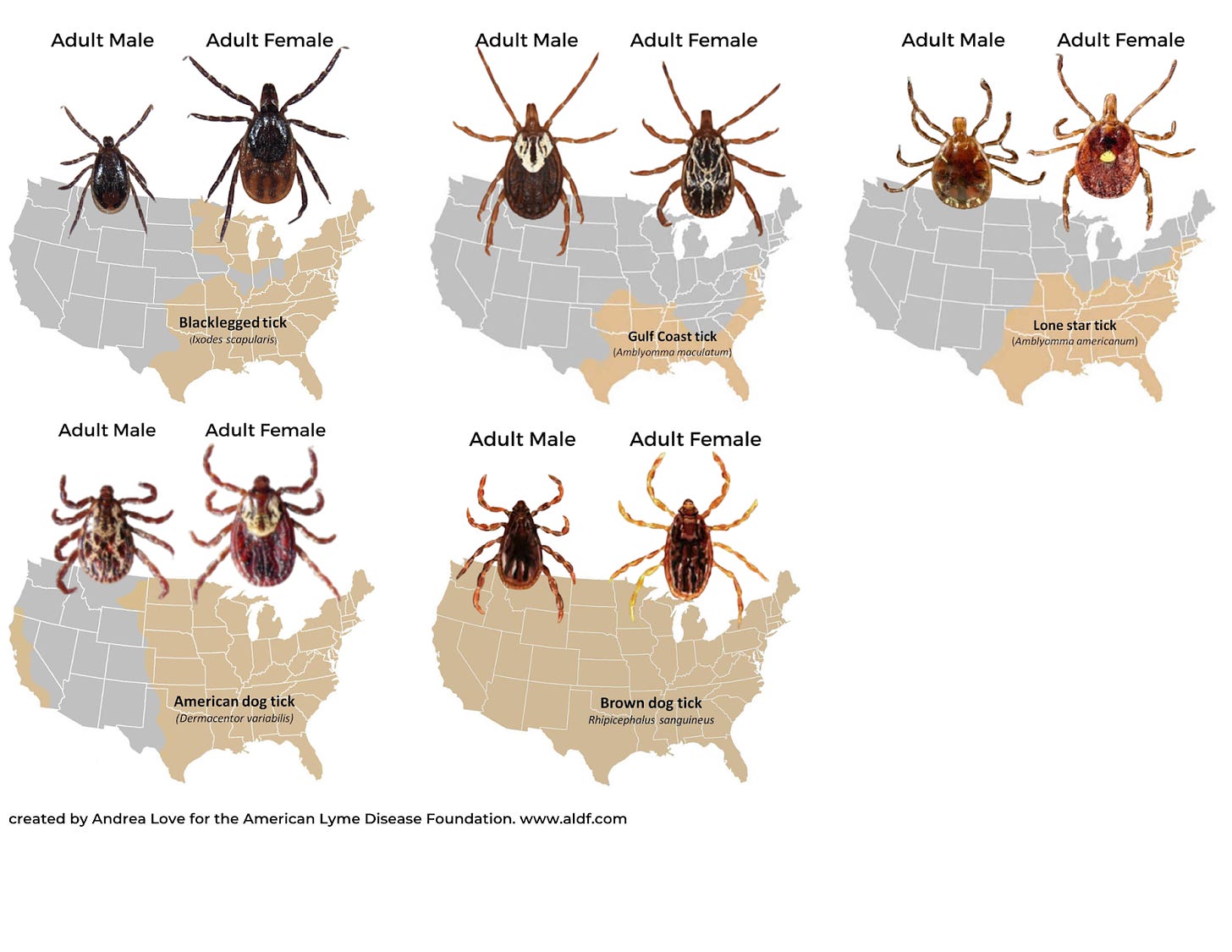

The most common TBD is Lyme disease, a bacterial infection transmitted by two species of ticks in the U.S. (concentrated in the Northeast and Midwest). Lyme is most common because the black-legged tick has a relatively broad distribution, and the bacteria have well-established populations in white-footed mice and white-tailed deer reservoirs.

Lyme disease occurs if Borrelia burgdorferi (the bacteria) evades the immune system at the tick bite, causing flu-like symptoms. Certain strains can cause more severe symptoms like neurological and cardiac issues, which occur in about 1-10% of Lyme cases.

Around 30,000-50,000 Lyme cases are reported in the U.S. every year, with 95% of cases occurring in 15 states. CDC generously estimates that up to 475,000 people could be infected annually. An important distinction in these estimates is CDC’s is based on people seeking antibiotic prescriptions for Lyme, a behavior influenced by public perception and misinformation (more on that in a little).

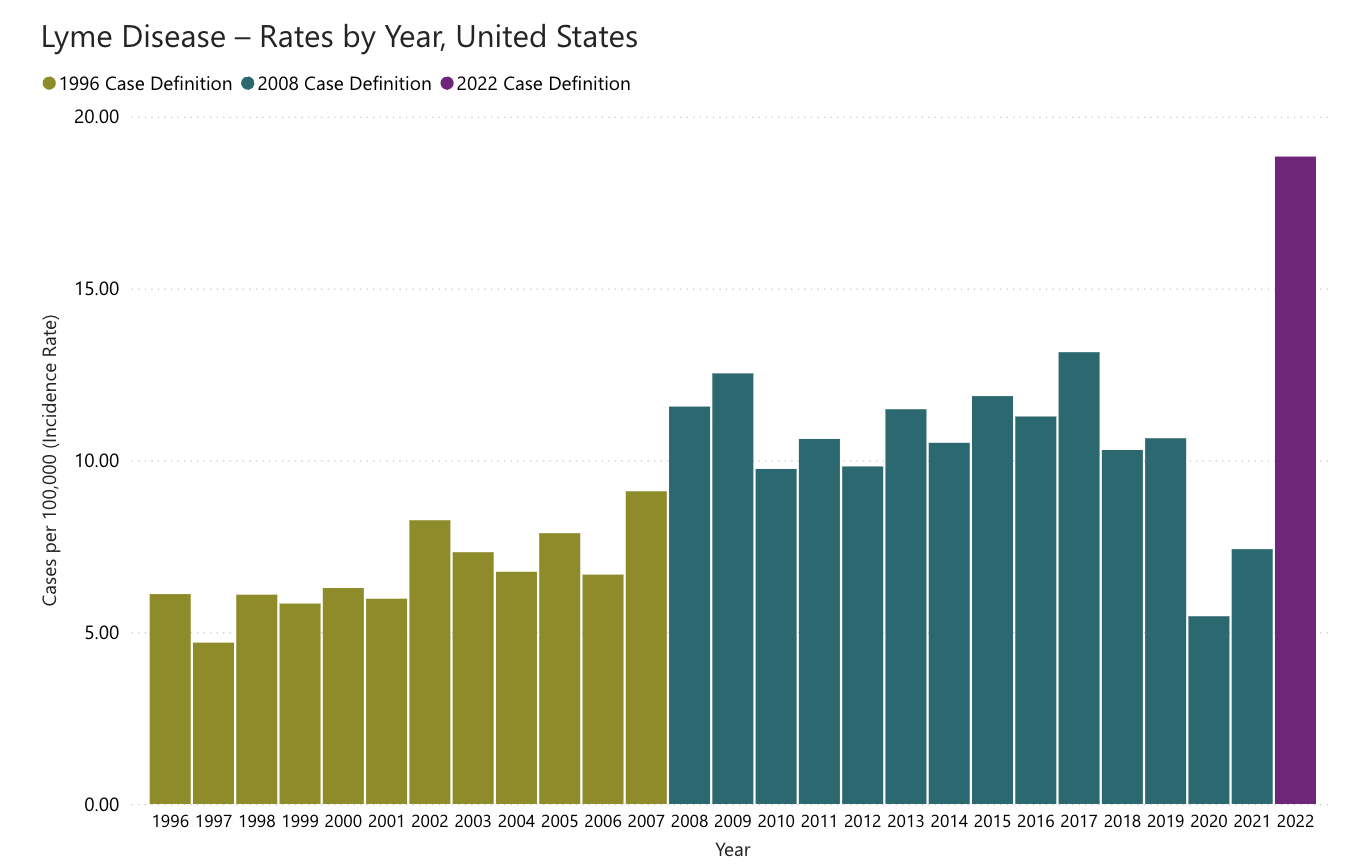

Confirmed Lyme disease has doubled since 1991, thanks to ticks’ expanding territory and improved ability to diagnose disease. (You’ll notice a big jump in 2022. However, this is due to a change in the definition rather than an increase in risk or spread of disease.)

The most fatal tick-borne disease in the U.S. is Rocky Mountain spotted fever (RMSF), but it is rare. Between 250 and 6,000 cases occur in the U.S. every year, and the mortality rate of RMSF can be up to 30% without prompt treatment. Most cases occur in five states (North Carolina, Tennessee, Oklahoma, Arkansas, and Missouri), transmitted by the American Dog Tick and the Brown Dog Tick. In recent years, the disease’s range has expanded, especially in parts of the Southwest (Arizona, New Mexico), where it particularly impacts Indigenous populations.

One of the most talked about TBD, beyond Lyme disease, is alpha-gal syndrome. Unlike other tick illnesses, alpha-gal syndrome is not an infection but a rare allergy to a sugar present in mammals that ticks feed on. It has been linked to the Lone Star tick, found primarily in Southeast but which is starting to creep North. Symptoms appear if a person consumes animal products containing alpha-gal. Current data suggest about 0.15% of the US population has been diagnosed with alpha-gal allergy.

Some common fact-checks

Tick-borne diseases, and Lyme disease in particular, are surrounded by misinformation as a result of a booming market of unapproved and inaccurate tests and treatments.

Here are a few of the top myths addressed:

Getting bitten by a tick DOES NOT guarantee you’ll get infected with something. In the case of Lyme disease, the risk of illness following a tick bite in an endemic area is 1-5%. In many places where black-legged ticks are found, only a small proportion of the ticks even carry the bacteria. Ticks also need to feed for a minimum amount of time to transmit diseases.

“Natural” or homemade tick repellents are NOT safer or more effective. DEET has over 70 years of data demonstrating safety and efficacy. Picaridin has over 25 years. Essential oil-based repellents are ineffective and can be dangerous, especially for young children and pets.

Non-standard tests and treatments are not appropriate alternatives to FDA and IDSA-approved methods. A complex and insidious network of fraudulent and inaccurate tests claims to diagnose Lyme and other tick-borne diseases.

Sending ticks in for testing plays a role in surveillance but not diagnosis. Finding something in a tick doesn’t mean it was transmitted to you after a tick bite.

We can still enjoy the outdoors!

We can implement multiple layers of effective measures to prevent tick bites. If we prevent tick bites, we prevent the risk of illness.

Insecticide on clothing: 0.5% permethrin kills ticks upon contact. It’s best to apply on shoes/pants. (Must let it dry fully, but it can last for several washes.)

EFFECTIVE repellents: DEET and picaridin are the only two with efficacy against ticks. 30% DEET and 20% picaridin protect for 6-8 hours.

Light-colored clothing and pants tucked into socks improve the visibility of crawling ticks on clothing.

Check for ticks: Ticks climb up your body, seeking a suitable feeding site (warm/moist/protected spots). It can take 15 minutes to hours for them to select a location (groin, navel, armpits, behind ears, etc). Check all your crevices after spending time outdoors.

Shower promptly after being in tick habitats—within 2 hours—to help wash off crawling ticks.

Remove ticks promptly: Most pathogens can only be transmitted if a tick feeds for a certain duration. Mechanical removal using tweezers is the only recommended method.

Tumble dry clothing on high to kill ticks in clothing. Ticks do not like low humidity levels in homes and will rapidly desiccate and die if they cannot find a host.

If you have pets that join you outside, they must be treated with ectoparasiticides. However, most of those require the tick to bite and feed to be killed, so you should also comb your pet (i.e., dog) after they come in from outdoors to remove crawling ticks that can end up in/on your clothing and furniture (and can climb onto you).

What about vaccines?

There are several we use for animals:

While Lyme is less likely to cause symptoms in dogs, a Lyme vaccine is available as a 2-dose injection plus an annual booster with 60-80% effectiveness. (Note: cats do NOT develop Lyme disease.)

An oral vaccine for wild mice targets Lyme disease by interrupting the transmission cycle: ticks cannot pick up the bacteria from mice, so they do not become infected and cannot transmit bacteria.

Vaccines for ticks are approved for livestock use in Cuba, Mexico, Argentina and others, to reduce the economic impact of cattle ticks that decimate livestock. Vaccine candidates aim to cause premature feeding of ticks, tick death upon attachment, inability to transmit pathogens, sterility, etc.

A human vaccine for Lyme disease by Pfizer/Valneva is in phase 3 clinical trials, with expected completion in 2025. An extremely effective Lyme Disease vaccine was available in 1998. But it was pulled from the market in 2002 when demand dropped following broad anti-vaccine sentiment due to Andrew Wakefield’s fraudulent paper on the MMR vaccine. Claims about adverse effects like arthritis were unfounded: the rates after vaccination were the same as before.

Bottom line

Tick season is getting longer, and geographical ranges are slowly but surely expanding. With this comes increasing misinformation. We can do a lot to avoid diseases these critters carry, and there may even be at least one vaccine on the way.

Love, YLE and AL

Andrea Love, PhD, is an immunologist and microbiologist who works full-time in life sciences biotech. Dr. Love is founder of ImmunoLogic and the Executive Director of the American Lyme Disease Foundation.

“Your Local Epidemiologist (YLE)” is written by Dr. Katelyn Jetelina, MPH PhD—an epidemiologist, wife, and mom of two little girls. During the day, she is a senior scientific consultant to a number of organizations, including CDC. At night, she writes this newsletter. Her main goal is to “translate” the ever-evolving public health science so that people will be well-equipped to make evidence-based decisions. This newsletter is free, thanks to the generous support of fellow YLE community members. To support this effort, subscribe below:

I sincerely appreciate your posts. As usual, this one is clearly communicated and includes action steps for preventive measures. Thank you, Dr. Jetelina and Dr. Love, for being my trusted source for health information.

A good run down thank you!

I would add that picaridin based repellents slightly edge out DEET in terms of ease of use and efficacy, and don’t forget that if you remove an engorged tick in a Lyme disease prevalent area (such as PA and NJ where I practice), a single dose of doxycycline 200mg reduces the risk of Lyme transmission to something like <1% chance:

https://www.cdc.gov/lyme/media/pdfs/Lyme-Disease-Prophylaxis-After-Tick-Bite-Poster.pdf