On my way back from Turkey, and there’s nothing quite like international travel to help put things into perspective. There are much bigger problems in this world right now than the mask debate.

Still, it would be tragic if people left the emergency thinking one of two extremes: “masks don’t work” or “any mask works.” Another pandemic will come, and we will need to be better and smarter. Hell, every winter, we could be smarter.

This post is to provide a sober perspective on the “story arc” of the science around masks—an attempt to communicate important nuances and provide clarity to a story that is not yet done.

The question

Everyone wants a one word answer to this question: Do masks work? But these three words strung together beg several loaded questions: What does “work” mean? What kind of mask? During what period of transmission? During what disease? In what social context?

All these questions and the answers are getting jumbled together for the public. This may be intentional (to make a point) or unintentional because people really want a simple answer to a complicated question.

Science has been moving at a lightning speed, and we’ve been discovering answers as we go.

Where did we start?

At the beginning of the pandemic, public health faced a decision: Do we recommend people wear masks? It’s hard to remember how limited information was at the time:

We had no data on masks and SARS-CoV-2. We relied on data for other viruses—influenza, and a handful of studies from SARS and MERS outbreaks. Some of these found no benefit, while others did find benefit.

We had no evidence—yet—of asymptomatic transmission. So recommendations said asymptomatic individuals should not wear masks, while people with COVID symptoms or those at high risk of exposure (health care workers) should wear masks.

We had critical shortage of PPE for healthcare.

Then, as the pandemic progressed, a few things changed:

We learned that even “healthy” people could transmit the virus (i.e., asymptomatic or pre-symptomatic transmission).

COVID spread like wildfire. Cases became much more common. Thus, those at risk of exposure eventually became “everyone.”

PPE supply was growing.

Scientists indicated concern about aerosol transmission.

COVID wasn’t going away. Social distancing indefinitely was not a viable option, and vaccines were months (years?) out. Masks represented a way to slow the spread as people started to resume (semi) normal lives.

People started wearing masks, countries and spaces started mandating, and scientists started studying specific questions.

Do masks work against SARS-CoV-2 in a lab?

The first scientific question that needed to be answered was: For the mask wearer, can masks physically stop droplets and aerosols coming in or going out?

This is a physics question. To answer it, scientists placed test subjects in very tightly controlled environments with equipment that precisely measured the number of particles that were released or inhaled with whispering, coughing, laughing, etc., while wearing different masks. The lab set up looked like something below:

Multiple studies showed that masks help protect the wearer against SARS-CoV-2 (i.e., reduce the number of particles inhaled by someone).

Also, masks reduced the number of particles emitted by a person. One study found that “surgical masks and KN95 reduce outward particle emission rates by 90% and 74%.”

The details mattered, though:

Filter (i.e. type of mask)

Size of infectious disease particles

Fit

For example, surgical masks work best against droplets. They can have aerosol impact but leak a lot. Cloth masks work for droplets too, but really don’t do much for aerosols. N95s are best, curbing spread via droplets and aerosols.

We still have a lot of unanswered questions, like: If surgical masks leak, can they still help reduce the viral load, and thus lead to less severe disease?

Do masks work on an individual level?

If masks work in a lab, they must prevent infections among individuals in the real world, right? Not necessarily. Tightly controlled environments are different from the real world. We’ve seen this in several studies during the pandemic:

People don’t wear them, even if recommended.

People wear them at different frequencies. The more someone wears a mask, the less likely they are to get an infection. (And, vice versa).

People adapt masks. Using two surgical masks worked better than one mask. Tying the strings on a surgical mask increased effectiveness.

Do masks work on a population level?

If masks work in a lab and sometimes on individuals, then if hundreds/thousands of people wear them perfectly and imperfectly at one time, will they reduce transmission during a pandemic?

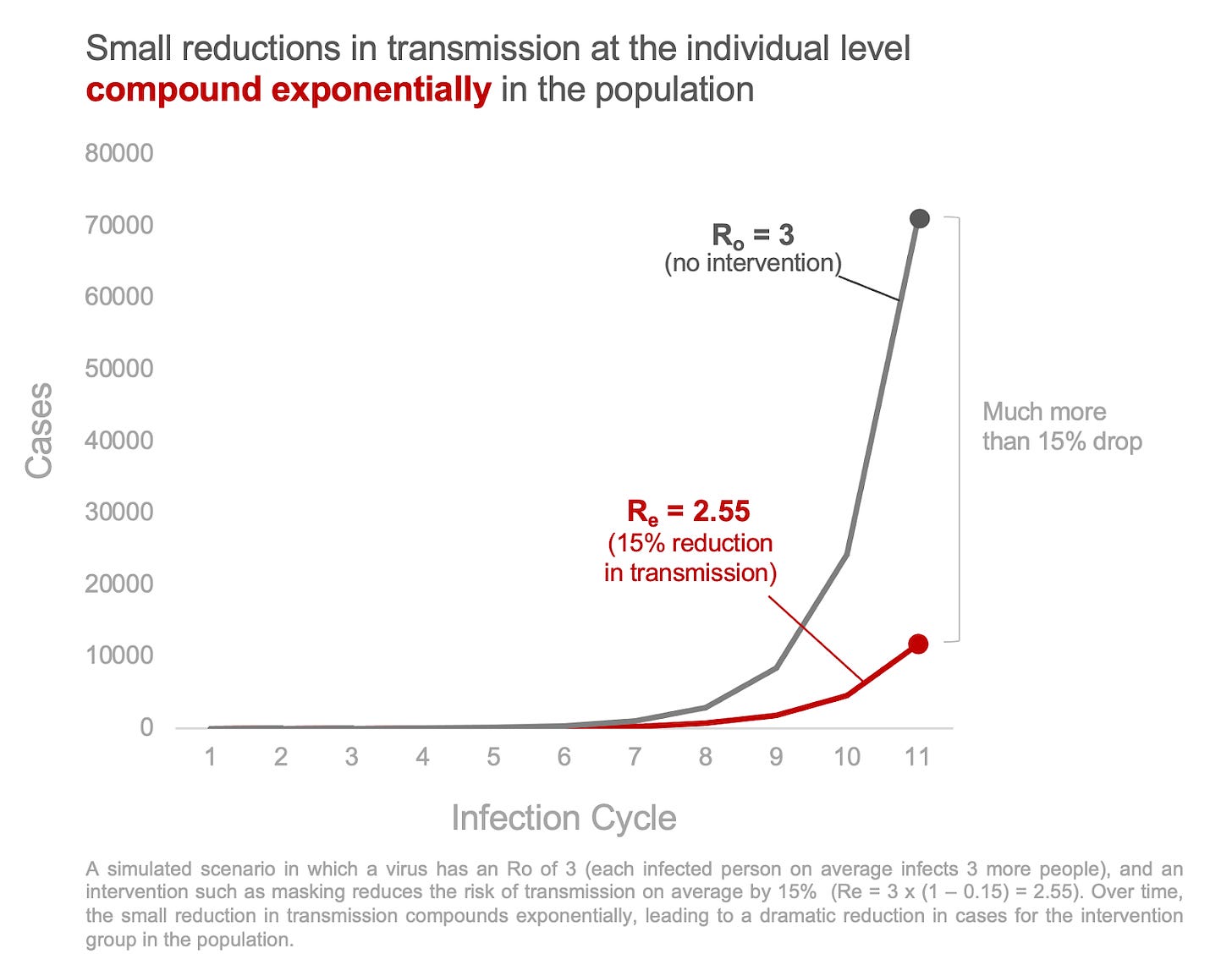

Viral transmission in a population is exponential. Even if masks only reduce the risk of transmission for each individual by a small fraction, when a community masks, those small effects compound exponentially across a population, making a big dent in cases. Just like compounding interest—a small change in the percentage makes a big difference down the road.

But how much do masks reduce transmission? Studies have attempted to answer this:

Mask wearing corresponded to a 19% decrease in the R(0) in one study. In other words, masks helped reduce transmission.

In Bangladesh villages were randomized to be provided free masks. Villages that got the intervention had more than double the mask usage than villages that didn’t (13% vs. 42%). This resulted in a 9% reduction in cases in the mask-wearing villages.

In the U.S., a 10% increase in mask wearing was associated with greater control of transmission.

In Germany, mask mandates reduced spread by 45%.

These studies found a huge range (9%-45%) and reflect vastly different settings and cultures. We need more studies. Many unanswered questions also remain: At what R(0) do masks not help? How many people have to wear them well to help reduce transmission (i.e. compliance)? How does social pressure or fear impact usage?

What are the policy options?

If masks help the individual and reduce transmission in the population, then what is the best “policy” during a pandemic?

Public health ethics suggests interventions must be designed around certain criteria: effectiveness (i.e., masks will achieve the public health goal), necessity (i.e., timing during a pandemic), proportionality (do benefits outweigh risks and moral norms), least infringement (least restrictive and least intrusive), impartiality, etc. Who carries the burden and when?

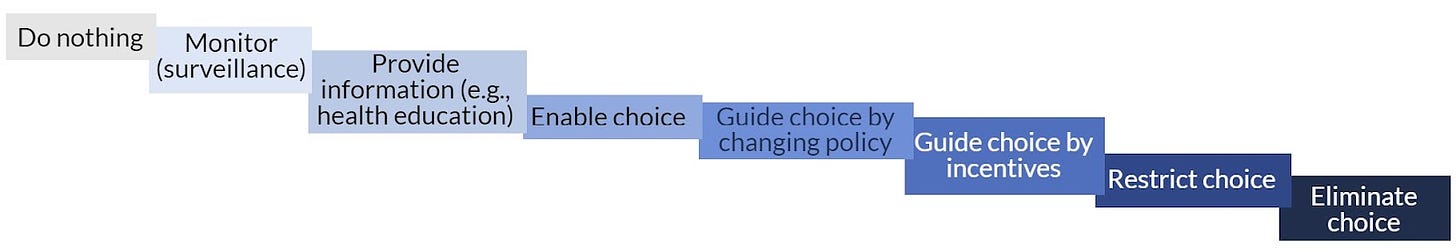

As the public health ethics “Intervention Ladder” outlines, we have many options ranging from least to most intrusive.

The effectiveness of some, but not all, of these strategies was tested throughout the pandemic:

Enable choice: Recommend masks. One randomized study in Denmark found this was weak and didn’t impact infections.

Guide choice by incentives: Hand masks out for free. This worked in Bangladesh.

Restrict choice: Mandate in certain spaces. Mandating masks in schools was shown to be highly effective in Boston. Other studies show effectiveness in healthcare settings (here, here, here).

Eliminate choice: Mandate everywhere. Some studies showed that mandates worked, especially in the early days of the pandemic (here, here, here, here). Other studies showed considerable weak evidence of mandates and subsequent wearing (here, here).

We have more work to do to understand what does and does not work when weighing social, moral, cultural, and epidemiological factors during an emergency.

Then, the Cochrane review was published and took social media by storm

Cochrane reviews are meta-analyses; they aren’t new studies, but rather attempts to pool studies to find an overall “answer.” Importantly, there have to be enough studies asking the same question, with the same intervention, and measuring the same outcome for this to be useful. This is why we don’t have meta-analyses for every scientific question. If done correctly, Cochrane reviews are incredibly powerful and typically respected in the scientific field.

This specific review included studies on non-pharmaceutical interventions, including masks. If we just look at the mask studies, the Cochrane review included 12 studies. But the details matter, as these studies:

Only included randomized control trials (RCTs). This is typical for meta-analyses as RCTs are the “gold standard” for scientific questions. But these RCTs had a number of problems and, given the limited number of RCTs on COVID-19, do not represent the totality of evidence (i.e., see all studies above).

Combined different viruses. When a virus is less contagious, an effect is harder to detect. Many of the RCTs evaluated influenza, which is far less contagious than COVID-19. This means that if we combine them, the impact of masks may be underestimated. (Another scientist, separate from this review, removed the flu studies and reran the meta-analysis. He found masks protected against SARS-CoV-2.)

Combined settings. Studies ranged from suburban schools to hospital wards in high‐income countries, crowded inner city settings in low‐income countries, and an immigrant neighborhood in a high‐income country.

Only asked one question. Does wearing a mask protect me? This ignores other important questions.

The authors of the review ultimately concluded there was no evidence of masks making a difference. On top of the limitations described above, keep in mind that “no evidence of a difference” is different from “evidence of no difference.” Don’t use an inconclusive Cochrane review to reject the value of masks, or any other intervention for that matter.

Where are we going?

All of the aforementioned studies have limitations. Every single one. No study is perfect. This is normal. Because of that, we have holes in our knowledge and, as we fill them, evidence will continue to evolve.

We now have the time, data, and energy (maybe?) to understand why, where, and how well masks work, so we can be better and smarter next time.

Bottom line

The scientific “arc” of mask discovery is ongoing. Science is always evolving. Do not let anyone convince you of a one word answer to the question: Do masks work? It depends.

Love, YLE and Dr. Panthagani

Kristen Panthagani, MD, PhD is an emergency medicine physician at Yale. In her free time, she is the creator of the medical blog You Can Know Things.

“Your Local Epidemiologist (YLE)” is written by Dr. Katelyn Jetelina, MPH PhD—an epidemiologist, data scientist, wife, and mom of two little girls. During the day she works at a nonpartisan health policy think tank and is a senior scientific consultant to a number of organizations, including the CDC. At night she writes this newsletter. Her main goal is to “translate” the ever-evolving public health science so that people will be well equipped to make evidence-based decisions. This newsletter is free thanks to the generous support of fellow YLE community members. To support this effort, subscribe below:

Thank you! Such awesome data! Per my personal experience, masks work! Family of four; we wore masks everywhere we went when necessary. We started out with cheap ones then got double fabric, then N95’s! We never got sick, fat maybe...lol but when we took off masks, we started getting sick. Head colds, allergies, the flu! So MASKS WORK!

What I don't understand is why the U.S., with its massive resources, has not studied the bejesus out of this question. After all the social upheaval we shouldn't have to cite Bangladeshi studies. I'm firmly pro-mask but I also am skeptical of forcing ineffective (cloth) measures on adolescents at such a social cost without proof.