Don't be surprised if masks come back to hospitals and nursing homes

The case for it, against it, and a big unanswered question

This will be the first winter with Covid-19 that we’re not in a public health emergency. This leaves a lot of questions open for the front line, like hospitals, health departments, and nursing homes, including: Do we reinstate mandatory masking in hospitals this fall/winter?

The scientific evidence shows a solid case for reinstating masks in hospitals and long-term care facilities. So much so that I think it’s worth pushing through the inertia.

Here’s the data’s story.

Setting the scene

Before the pandemic, hospitals ran on an average of ~65% occupancy. Wiggle room was built in, but in pre-pandemic times, it wasn’t unusual for hospitals to reach capacity during a bad flu season, especially in pediatric hospitals and ICUs.

The pandemic brought new realities:

We have a new virus in our repertoire of threats.

We have not increased our capacity.

Healthcare workers are burnt out and leaving in droves.

We have learned a ton about viruses, transmission, and available tools to help.

Enter the case for masks

Masks are one tool that can help keep capacity down and workers and patients healthy.

In-hospital respiratory infections are a problem, particularly for kids. If you go to a hospital, you’re at risk of getting an infection you didn’t have when entering the door. This isn’t new; nosocomial infections, like surgical site infections, ventilator-associated pneumonia, and catheter-associated urinary tract infections, have been a problem for decades.

We also see hospital acquired respiratory illnesses:

One study (pre-pandemic) found in-hospital respiratory infections were 5 cases per 10,000 adult admissions; 44 cases per 10,000 pediatric admissions.

13% of people died from in-hospital respiratory infections.

2 of 3 in-hospital respiratory infections occurred during the fall and winter.

Another study (during the pandemic) of 288 hospitals found that 4.4% of hospitalizations were due to in-hospital Covid-19 infections.

Community transmission increases hospital transmission. Close quarters, close contact, vulnerable people.

One study found a 10% increase in community-onset SARS-CoV-2 infection rate was associated with a 178% increase in the hospital-onset infection rate.

Healthcare workers come to work sick. High workload burden, a sense of personal responsibility, a lack of paid sick time, and perceived expectations. This results in:

A significant proportion (15-70%) coming to work sick with flu, for example.

A Covid-19 study found 50% presenteeism while sick with symptoms.

Masks work . . . especially in hospitals.

Masks work on individuals. We have limited evidence on whether they work to reduce population-level transmission. But some of the most substantial evidence is in hospitals:

A large clinical trial (pre-pandemic) found bacterial and viral infections were significantly lower among healthcare workers who continuously wore an N95 compared to other study groups, like those who wore a surgical mask or no mask at all.

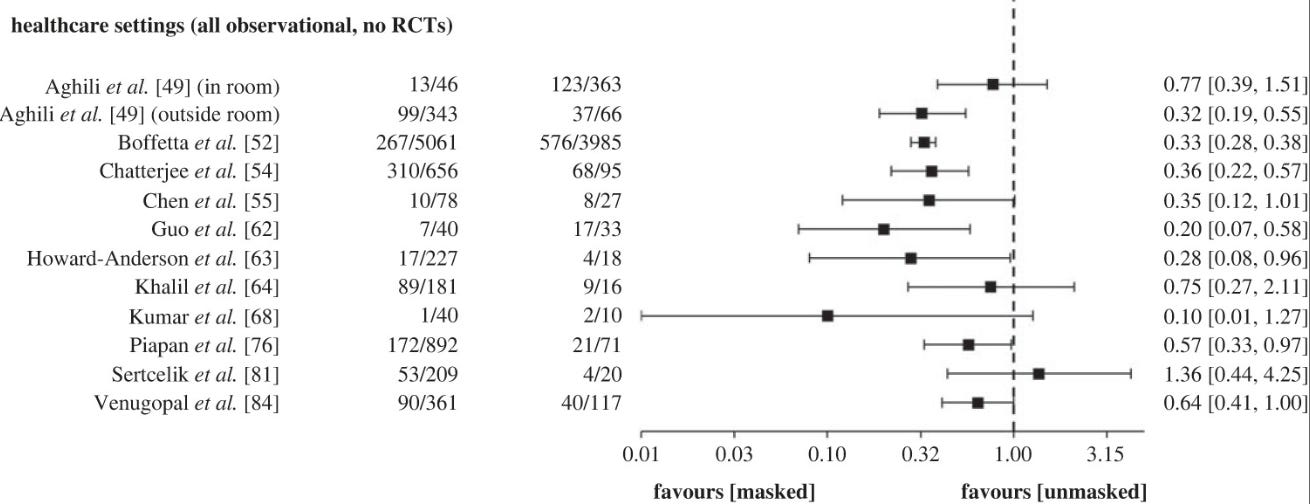

One review examined 40 studies on masks in healthcare settings (one randomized controlled trial and 39 observational studies). The majority of studies favored masking vs. not masking in healthcare.

What is the case for not making masks mandatory in hospitals?

There are a few reasons I’ve heard (beyond the normal “masks don’t work” argument):

We didn’t do it in pre-pandemic times.

For the public, this is true. Donning a mask as a personal measure to prevent hospital infections is a new step we’ve taken during the pandemic. This is a highly contagious virus. And we’ve learned leaps and bounds, like the role of asymptomatic disease and viral transmission routes.

For healthcare workers, masks have been a core tool for decades, especially when managing patients with potential respiratory infections. The questions are really when and where? Tossing the mask altogether has never been on the table in high-risk healthcare settings.

Negatively impacts healthcare workers. One study in Singapore found that one-third of nurses said wearing masks negatively affected their work, such as discomfort, frequent adjustment, and inability to concentrate.

Are these infections preventable? Hospital-onset Covid-19 infections occurred at similar rates as other health care–associated infections, like UTIs. A national goal is to reduce these, but this raises a good question about how preventable in-hospital respiratory infections are.

“I thought we were done with mandates!” There is a distinction between public mandates aimed at the population as a whole and a much narrower mandate for specific high-risk settings. If you don’t set foot in a hospital or long-term care facility, most (all?) mask orders won’t impact you.

The biggest question remains

If masks are reinstated, what are the on- and off-ramps, if any? There are a few options:

Keep mandatory masking throughout the year.

Universal masking during a window of time. For example, Marin County has decided to mask in hospitals from November through March after looking at respiratory trends in wastewater data.

Universal masking in high-risk units, like organ transplants and oncology. (Although there are high-risk patients throughout the hospital.)

Require masks based on hospital capacity. But what capacity? This would be confusing to patients going to different hospitals.

Like any policy, where you land on this ultimately comes down to values. (And we know nothing gets people’s blood boiling more than masks.)

Bottom line

Do not be surprised if hospitals and long-term care facilities return to mandatory masking soon. Some have already announced that they are coming down the pipeline.

Infectious diseases violate the assumption of independence— what we do directly impacts those around us. A low-cost, minimally invasive intervention, like masking, is a great way to start protecting our community’s highest-risk individuals this fall and winter season.

Love, YLE

“Your Local Epidemiologist (YLE)” is written by Dr. Katelyn Jetelina, M.P.H. Ph.D.—an epidemiologist, wife, and mom of two little girls. During the day, she is a senior scientific consultant to several organizations. At night, she writes this newsletter. Her main goal is to “translate” the ever-evolving public health world so that people will be well-equipped to make evidence-based decisions. This newsletter is free, thanks to the generous support of fellow YLE community members. To support this effort, subscribe below:

Thank you for this review. As a family doc in small examining rooms I’ve never stopped wearing an N95. It has never failed me (or failed to protect my patients).

As an older physician, married to an older dentist: I remember when we didn't wear gloves, and the huge push back when we started in the 1980's--"do you think I have AIDS??" My husband was always appalled that I didn't wear a mask with patients when they had respiratory illness. If we've learned anything, it's that universal precautions should be updated. We now understand airborne transmission: so update universal precautions. It should be simple, but there's so much vitriol and polarization. Thank you Katelyn, as always!