Don’t let mosquitos drain the last of summer fun

Mosquitos in the news

There is a lot of news about mosquitos and diseases right now:

West Nile Virus was highlighted by Dr. Anthony Fauci's hospitalization.

Eastern Equine Encephalitis (EEE)—a rare but severe viral illness—led to a death in New Hampshire.

Oropouche (aka “sloth fever”) has caused a new travel advisory urging pregnant women to avoid travel to areas with outbreaks, such as Brazil, Peru, Bolivia, Colombia, and Cuba.

A dengue fever emergency continues to ravage Puerto Rico.

So, what’s going on?

This is a “middle-of-the-road” season for some diseases.

Mosquito-borne diseases are not new to the U.S. They’ve remained relatively low in the mainland since the mid-20th century due to a nationwide campaign that effectively eradicated malaria through widespread insecticide spraying and other control measures, like draining swamps, using air conditioning, and providing quality healthcare.

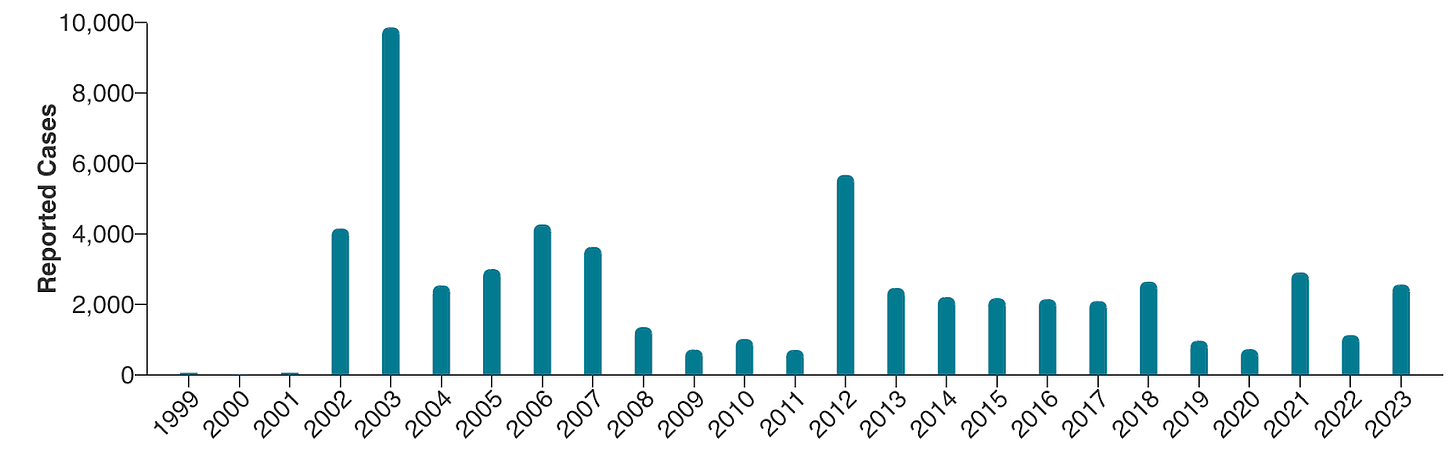

West Nile is the leading cause of mosquito-borne disease in the U.S. It is a fairly new disease—25 years ago, we didn’t have it around. But this year isn’t particularly bad. So far, in 2024, 235 cases have been reported to the CDC, which is similar (if not less) than in previous years.

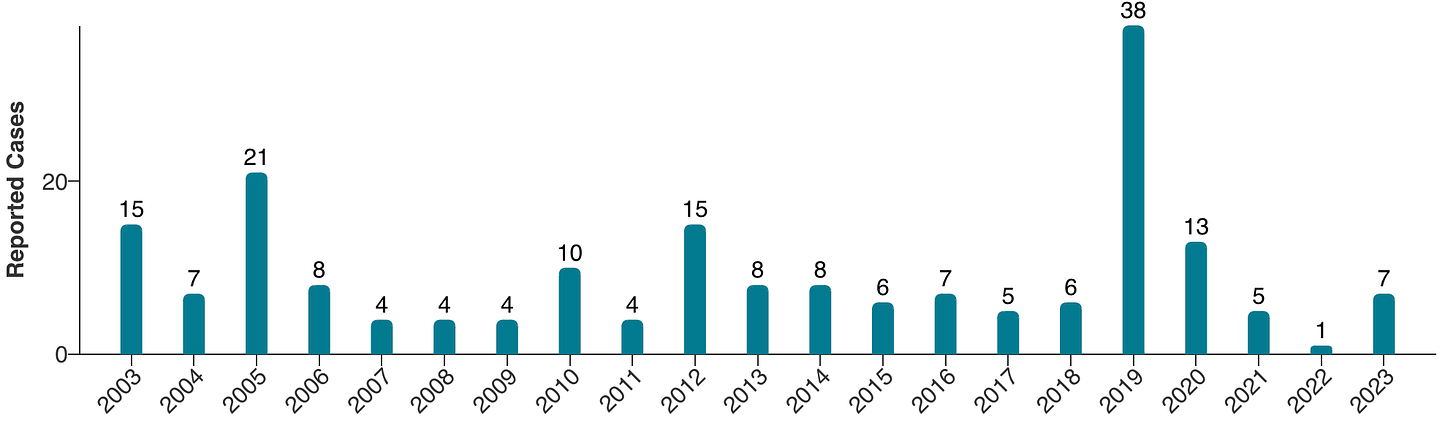

Same with EEE—the rare disease that caused a death in New Hampshire. In the U.S., we’ve had 4 cases this year, which is about on par compared to previous years.

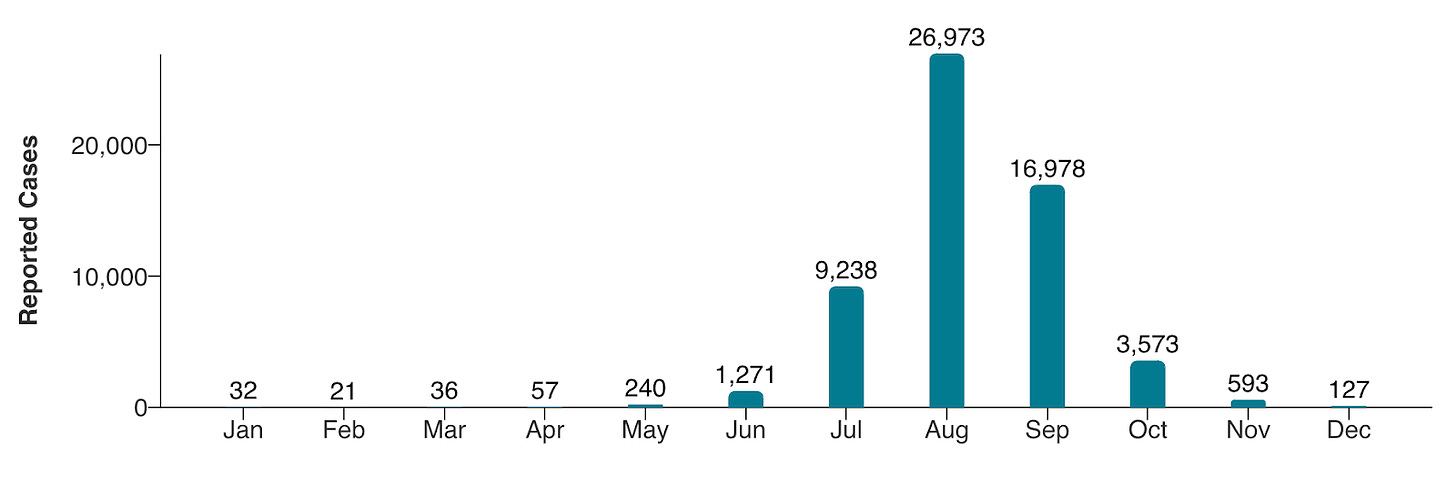

Mosquito-borne diseases are most common during August and September. Mosquitos are cold-blooded, so transmission is a bit like a chemistry experiment. If it’s too cold (below ~16°C, or ~60°F), the mosquito life cycle slows down too much to spread disease. Closer to the “magic temperature” of ~25°C (77°F), mosquitos are happier—and diseases spread a little more easily from mosquito to human.

But other mosquito diseases are on the rise.

With warming temperatures and changing climates, evidence shows that the habitat of some mosquitos is migrating, thus increasing the number of cases in the U.S. There is also more global travel (humans bringing disease and mosquitos) and more land being developed.

For example, this year, there have been 2,782 locally acquired dengue fever cases in the U.S. (specifically in Puerto Rico, Virgin Islands, and Florida). While cases have slowly increased in the U.S., globally, they have exploded 8-fold since 2000.

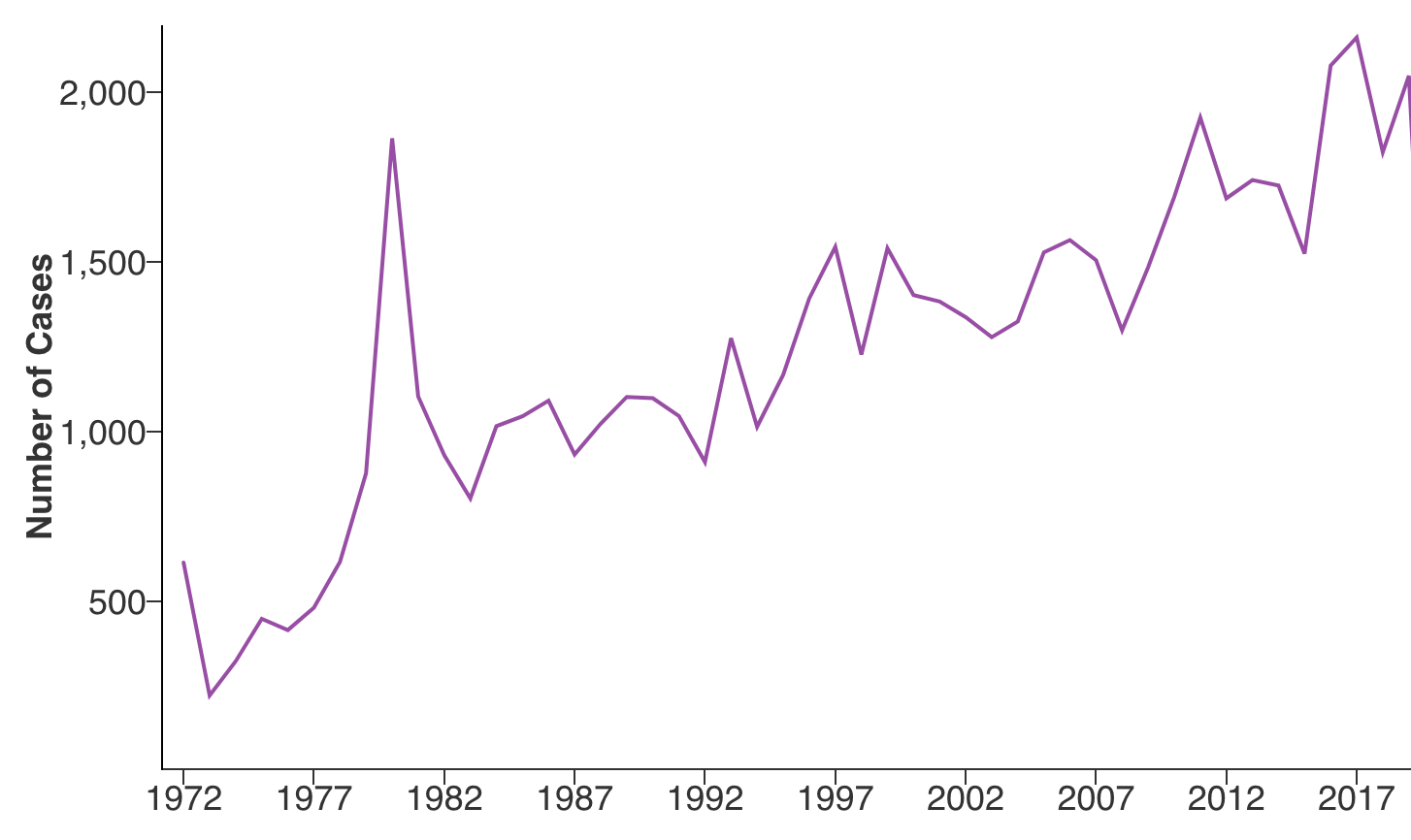

We also see an increase in travel-related malaria cases over time. (See the previous YLE post on what drives this.)

So, how concerned should we be?

While the spread of mosquito habitats is concerning, and there is much in the news, here are a few things to keep in mind:

In the U.S., severe disease is rare in the grand scheme of “things trying to kill you every day.” Each year, they cause about 35 to 70 deaths combined and millions of infections (most of which are asymptomatic). In the rest of the world, however, mosquitos are the number one killer—more than one million people worldwide die from mosquito-borne diseases yearly.

Risk is not uniform. For West Nile, the most impacted by severe disease are older adults (like Dr. Fauci) and immunocompromised. Pregnant women are particularly vulnerable to certain mosquito-borne diseases like Zika virus because it can be transmitted from mother to fetus, potentially causing birth defects. The biggest risk for Dengue is a second infection of dengue, causing a potentially deadly disease.

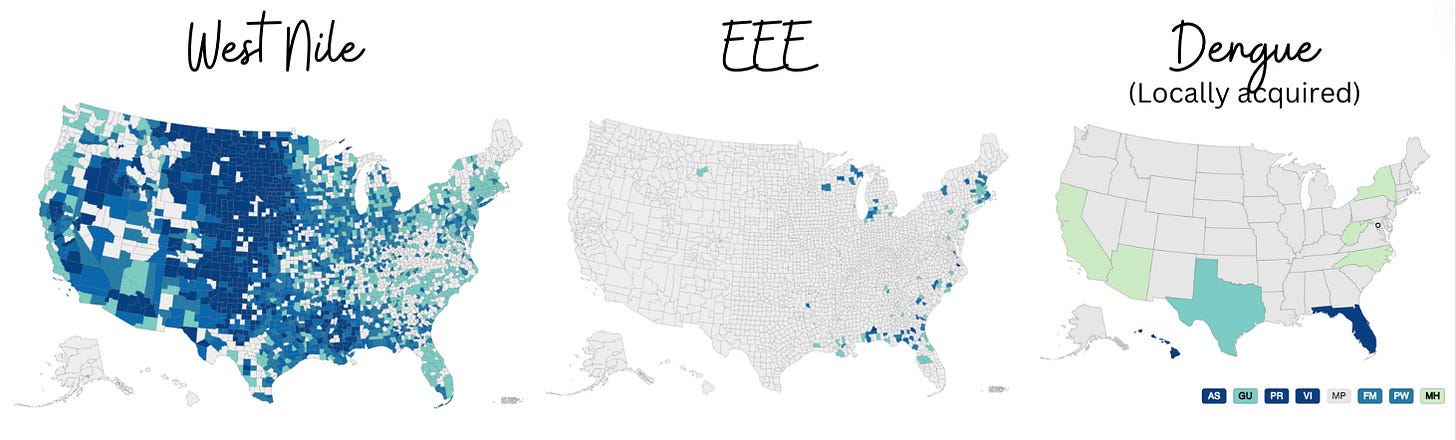

Also, geographic risk is not uniform. This is because many different types of mosquitos; not all carry the same diseases. EEE is mainly found in the Eastern U.S. (hence the “east” in its name). West Nile virus is most commonly reported in the Central and Western U.S. Dengue fever is primarily a concern in tropical and subtropical regions.

There is a lot we can do. While many ideal strategies exist, we also need to be practical. Let’s face it—we can't always limit our time outdoors during peak mosquito hours of dawn and dusk. The goal is to do what you can when you can.

Your best personal defense? EPA-recommended insect repellents, especially those with DEET. They really do work. Apply (and reapply) if you’re headed outdoors. Fun fact: DEET repels insects without killing them. Importantly, it doesn't harm beneficial insects like pollinators and doesn’t accumulate in ecosystems.

We have over 60 years of research supporting DEET’s safety and effectiveness.

Picaridin is a popular alternative to DEET because it is effective and gentle on the skin.

Some people turn to oil of eucalyptus (OLE) as a “natural” alternative to synthetic repellents. While some data supports its use, OLE is typically less effective than DEET or picaridin. Interestingly, while often marketed as “chemical-free,” OLE contains up to 100 chemicals, whereas DEET is a single compound!

Other strategies:

Wear protective clothing: Long-sleeved shirts and long pants when outdoors.

Eliminate standing water.

Maintain your yard: Keep grass cut short and shrubs trimmed.

Use physical barriers: Install or repair screens on windows and doors.

Use fans outdoors: Mosquitos are weak flyers and have trouble navigating in the wind.

Bottom line

Mosquito bites can be more than just itchy annoyances; they can be gateways for potentially life-threatening diseases. But we’ve been dealing with these tiny buzzers for ages, and a few smart habits go a long way in keeping them at bay.

Love, YLE and JS

Big thanks to Dr. Miguel Arturo Saldaña—arbovirologist— for fact-checking late last night.

Dr. Jessica Steier is a public health scientist with expertise in policy evaluation. She also leads Unbiased Science—a science communication organization that provides practical and accessible health and science information to the public.

“Your Local Epidemiologist (YLE)” is founded and operated by Dr. Katelyn Jetelina, MPH PhD—an epidemiologist, data scientist, wife, and mom of two little girls. During the day, she is a senior scientific consultant to a number of organizations, including the CDC. At night, she writes this newsletter. Her main goal is to “translate” the ever-evolving public health science so that people will be well-equipped to make evidence-based decisions. This newsletter is free, thanks to the generous support of fellow YLE community members. To support this effort, subscribe below:

The first time I heard fans suggested here was a "Duh" moment. All those years of citronella candles and tiki torches--and it turns out a couple of oscillators that also provide a cool breeze were all we needed. "Mosquitoes aren't strong fliers" is also pretty funny when you think about it.

For more control in the yard, mosquito dunk traps are a good alternative to spraying. Put some straw in a bucket, cover with water so it will ferment a little, and it becomes an irresistible place for mosquitoes to lay eggs. Add a "mosquito dunk" (a little smaller than a hockey puck, sold at hardware stores or online), which kills the larvae, cover with a screen, and place some distance from the house/patio. It attracts them away from you, and stops their reproduction, without harming pollinators.

https://www.popsci.com/diy/how-to-build-a-mosquito-kill-bucket/

If we had point of care testing for West Nile Virus infections in primary care and urgent care settings we would pick up so many more cases.

I’m also guessing Dr Fauci was diagnosed because either he suggested the test as an ID specialist, or his 103 fever sparked a good work up. Most cases are missed like you said.

Mosquito dunks are good for very local control, too - and more targeted with minimal collateral harm to other insects.