Emergency rooms are not okay

It has now reached a crisis point. It is killing people.

We are slowly coming down from a peak in respiratory illness. This past winter was a real test. How will our hospitals—the safety net of our society—fare, given the combination of:

Year 4 of a pandemic with a new threat to our repertoire,

A recent surge of respiratory viruses,

An aging population, and,

A massive infrastructure problem decades in the making.

The answer is in—our hospitals are overwhelmed. And it has now reached a crisis point. It is killing people.

Emergency medicine doctors across the country have been sounding the alarm. Americans are noticing it too. In a recent poll, nearly half of Americans said they avoid the ER—avoid critical care they need—given the wait times.

Here’s what is happening on the front line and how to fix it.

A dangerous hospital overload problem called “boarding”

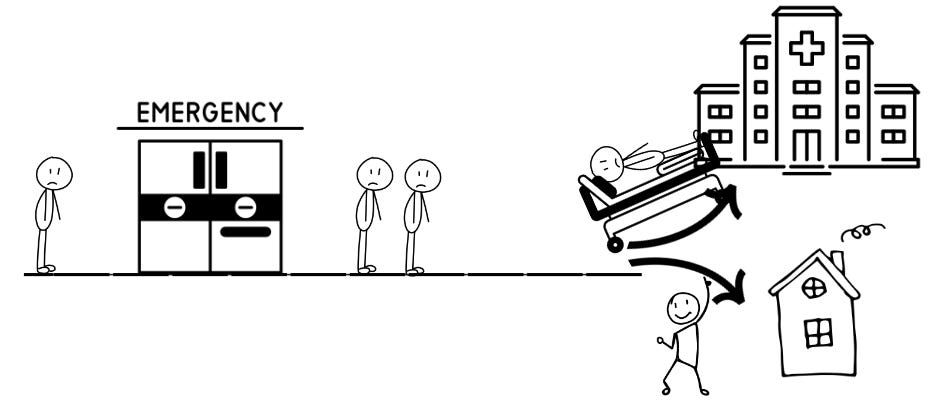

The emergency room (ER) is the front door of the hospital. Patients come and are quickly seen by a physician, who addresses medical emergencies and other needs. After evaluation and treatment, many are well enough to go home, and some require admission to the hospital. Those admitted patients are seen by the inpatient team of doctors and taken to a hospital bed upstairs.

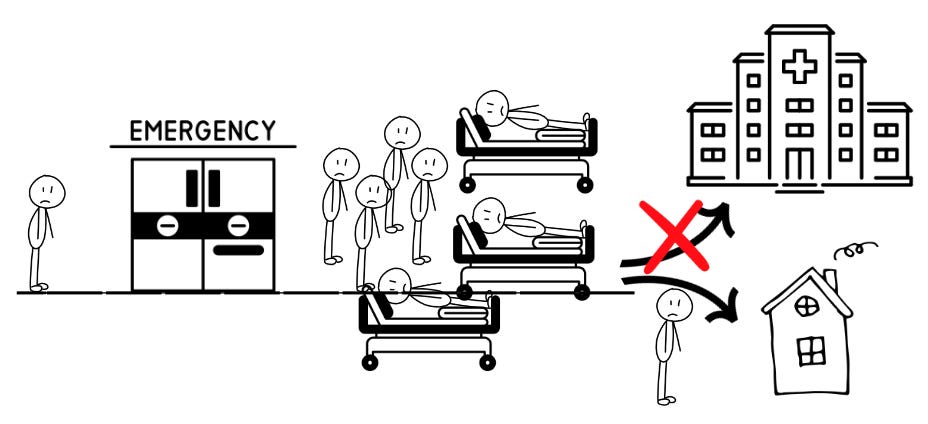

But what if there are no open beds upstairs? Those patients wait in the ER until a bed opens. These patients are called “boarders.”

Over the last two decades, this problem has grown and grown, causing a nasty clog. We haven’t fixed it, and it’s now overwhelming ERs nationwide.

The fallout

Boarding patients are waiting hours, days, or even weeks in the ER. It creates an unsafe environment for patients:

Dangerous medical errors: ER boarding is associated with increased medical errors, worse patient outcomes, and higher risk of in-hospital death. A recent study found that an extra hour of boarding was associated with a 16.7% increase in the odds they would require a higher level of care in the hospital (i.e., they were going to the floor, but now need the ICU.)

Death: In a nationwide survey, multiple ER physicians reported deaths that occurred because their ER was overwhelmed with boarding. For some, the backlog of patients is so bad that patients are dying in the waiting room before they can see a doctor.

Here’s why:

Waiting too long. Critically ill patients in the waiting room may not be recognized fast enough, and patients may leave because of the wait, only to come back the next day much sicker than before.

Unsafe nursing ratios. Unlike inpatient floors and the ICU, there are often no caps on the number of patients an ER nurse is assigned. In the ICU, each nurse has 1-2 patients. In the ER, a single nurse can have 7 patients or more, some requiring ICU level of care.

No inpatient doctor. Normally when a patient is admitted to the hospital, the ER doctor’s role ends and the inpatient doctor takes over, freeing up the emergency physician to see new patients. For boarding patients, often there is no inpatient doctor. Instead, emergency physicians are ordering critical medications and checking on boarding patients when they can. But realistically, they can only do so much while still responding to all the new cardiac arrests and strokes coming through the door.

Why is boarding happening?

The primary problem is not the number of patients coming to the ER. It’s the lack of open beds upstairs. A recent NEJM commentary provided some insight:

No buffer in the hospital. To optimize revenue, hospitals try to keep their beds full, which means there’s little buffer for predictable surges of patients.

Weekend delays. Many hospital operations stop on weekends. Patients who otherwise could be discharged are delayed because a service they need is not available.

Prioritizing elective surgeries. Elective surgeries bring in more money, so sometimes hospitals prioritize beds for surgeries instead of sick patients waiting in the ER.

Nursing home shortages. Sometimes patients are ready to be discharged, but no nursing home bed is available. (Or a bed is available, but their insurance hasn’t approved it yet.)

Staffing shortages. As we learned during the pandemic, it doesn’t matter if we have an open bed upstairs if there isn’t staff for it.

How do we fix this?

Hospitals are financially disincentivized from fixing this problem. We need regulatory institutions to step in. The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) is a strong player as they certify hospitals to receive Medicare funds, define safety standards, can require public reporting of hospital data, and manage many “pay for performance” programs. If CMS approves a new quality measure focused on boarding, it has the potential to do 3 things:

Get data. We do not have national data on the boarding crisis because hospitals are not required to report it. We are dependent on on-the-ground anecdotes, which hospital staff are often afraid to share. CMS can require public reporting of this data.

Set standards. Currently, there are no standards defining how long patients can board in the ER or how many patients a single ER nurse can cover.

Create better financial incentives. Once publicly reported, quality measures may be used in pay-for-performance programs that would reward hospitals that best manage capacity challenges by minimizing boarding.

A new CMS clinical quality measure on boarding is finally in the works, but it’s not yet approved. For a limited time (until February 16, 2024), the public can comment on this proposed measure and provide input. Typically, only parties invested in ignoring the problem comment. I’m asking you to change that:

ER physicians/nurses/staff: Look at the proposed metrics to track boarding, and provide any input you have here. These are metrics that hospitals would be required to report if the CMS measure is approved.

Everyone else: If you don’t have the time or experience to comment on the specific metrics, then go to the second page of the survey, and tell your stories about ER boarding. Thousands of responses from all of you will show CMS this is a giant problem that needs to be fixed.

Bottom line

Emergency rooms are the only place in the U.S. healthcare system that will never turn a patient away. And we don’t want them to. But a backlogged ER is the canary in the coal mine—our inadequate healthcare infrastructure showing its massive cracks. It is unsafe, and we must fix this.

Love, KP and YLE

Kristen Panthagani, MD, PhD is an emergency medicine physician at Yale. In her free time, she is the creator of the medical blog You Can Know Things. You can subscribe to her newsletter here.

“Your Local Epidemiologist (YLE)” is written by Dr. Katelyn Jetelina, M.P.H. Ph.D.—an epidemiologist, wife, and mom of two little girls. During the day, she is a senior scientific consultant to several organizations, including CDC. At night, she writes this newsletter. Her main goal is to “translate” the ever-evolving public health world so that people will be well-equipped to make evidence-based decisions. This newsletter is free, thanks to the generous support of fellow YLE community members. To support this effort, subscribe below:

Your excellent exposé about acutely overcrowded emergency rooms leaves out another, significant, contributing etiology: a chronic, severe shortage of psychiatric hospital beds and other, less-intensive mental health treatment resources that could and ought to accept and treat patients. Psychiatric treatment has long been woefully underfunded: non-government hospitals lose money on psychiatric inpatient care, and tight government budgets (coinciding with an unwillingness to increase revenues) translate into insufficient state (or other) government-run hospitals. In Vermont, my home state, hospitals are small; yet at any time, up to a dozen psychiatric patients end up being boarded in ERs for up to weeks at a time. Over the years, community hospital ERs have created quasi-psych units for these patients, but these rely on ER staffs, with occasional psych consultations, to provide oversight for these patients. Until third party payers, governments, and society at large appreciate that dollars up front for psychiatric care translate into substantial financial savings (not to mentioned improved psychiatric and general medical well-being), this problem is only going to get worse.

As a retired physician I am very familiar with the problems you cite. There is one simple fix that would make an immediate difference: moving to fully staffed 7 days a week hospital and outpatient services. It makes no sense that expensive hospital facilities like OR’s, cath labs, and endoscopy suites sit idle on weekends while patients are parked in scarce hospital beds awaiting their procedures. It is equally absurd that large primary care and multispecialty practices limit weekend outpatient services, forcing patients into urgent care centers and ER’s. The logistic challenges and costs are real but not insurmountable, and the resulting efficiencies will translate into lower expenses, higher profits, better outcomes and greater patient satisfaction. Walmart manages to keep its stores fully open all year round. Why can’t Humana, Sentara, HCA, Kaiser-Permanente and the VA do the same?