Last week, the Florida State Surgeon General issued new guidance on the COVID vaccines based on an analysis they performed. One of their findings: “an increased risk of cardiac-related death among men 18-39” for the mRNA vaccines. The state of Florida no longer recommends vaccines for this group.

Many scientists and clinicians voiced deep concerns with this Florida analysis. Numerous responses have shown why the methods and results were flawed and, thus, lead to inaccurate conclusions and poor health policy decisions. (For example, see this really great blog by Kristen Panthagani, MD, PhD.)

But millions of young people do have a legitimate question about the fall booster: Do I really need a COVID19 fall booster?

I have heard this question from many people I greatly respect. The only way to answer this is to weigh the benefits against the risks.

Risks

There is a very rare, but real risk of the COVID-19 vaccine for young males: myocarditis or inflammation of the heart muscle. We don’t know why this happens, but we think it’s due to the combination of hormones, dosage of RNA, and genes.

The U.S. (and other countries) have tracked myocarditis since this safety signal was detected last summer. The latest surveillance data was presented at the September ACIP meeting:

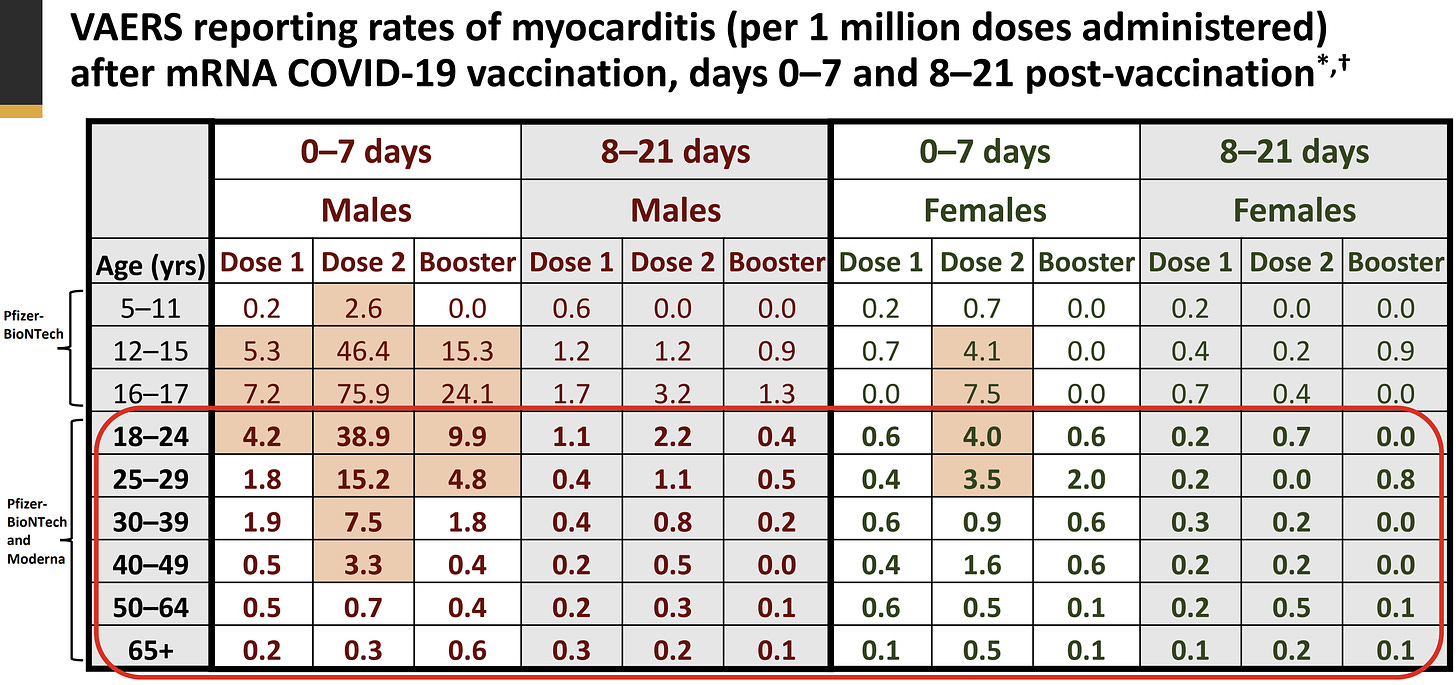

How often does it happen? According to VAERS data, for every 1 million booster doses administered among males aged 18 to 29 years old, we can expect 5-10 myocarditis events.

VSD data (medical records from 9 hospital systems across the U.S.) show the risk of myocarditis is higher at about 42 cases per 1 million doses among 18-29 year olds. (Among 166,973 males aged 18-29 years old who got the first booster, 7 had myocarditis.) In peer-reviewed studies, the rate of myocarditis is a bit higher for the booster. For example, 112 per 1 million doses among young military men in Israel (although with a different definition of myocarditis, so compare with caution). Regardless, the “background risk” of myocarditis (i.e., of getting it from other viruses) is ~0.2 to 2.2 per 1 million. So, there is a link between vaccines and myocarditis.

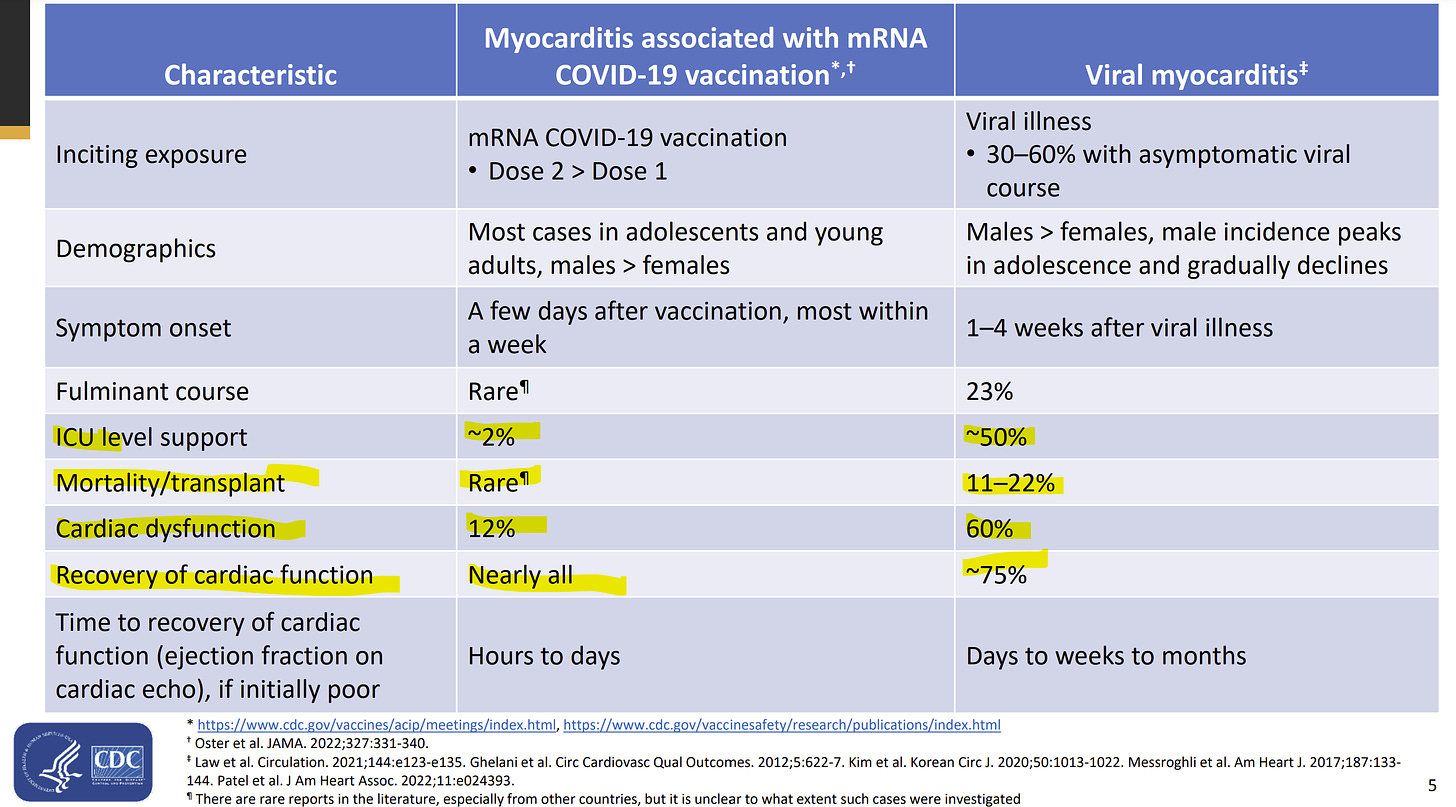

How severe is it? Myocarditis, like any disease, is not binary; it can range from asymptomatic to severe. Thankfully, myocarditis after the vaccine is relatively mild: 2% go to the ICU and nearly all fully recover. There have been deaths, but the causal link (was it caused by a virus or the actual vaccine?) is still under investigation and unclear. Myocarditis severity after a viral infection is much higher: 50% go to the ICU, 25% do not fully recover, and 11-22% die. Notice all these numbers are from peer-reviewed scientific articles below.

Another risk to the vaccine is inconvenience: possibly getting a fever, possibly missing work. And this can be a big deal for some people and families.

Benefits

Benefits of the booster for younger populations are still there, but they may not be as apparent as the benefit from the primary series. The primary goal of the vaccine is to prevent hospitalization and death. The average, healthy young male will not go to the hospital and die from COVID-19 if he goes unboosted this fall.

But, there are subtle benefits aside from preventing severe disease:

Prevents myocarditis. You can get myocarditis after SARS-CoV-2 infection, too. And, it’s typically more severe than the vaccine (see studies above). A study published in Nature found that the rate of myocarditis was higher after infection compared to after vaccines among all ages. (A CDC study showed the same thing.) But when we just look at people under 40, the rate of myocarditis after a second dose was higher than the risk from infection (see figure below). This was not the case for other heart problems, like pericarditis and cardiac arrhythmias, in which the virus was far more risky than a vaccine. To my knowledge, we don’t know what this graph looks like for boosters. Myocarditis after a booster, in general, is less risky because there is more time between doses. I would expect those bars to switch, but we desperately need to update this.

Long COVID. Vaccines reduce the risk of long COVID19. We don’t know by how much, as some studies say 15% reduction in risk and some say 85%. The “true” rate is somewhere in-between.

Broader protection. Very recent data shows the fall booster expands and diversifies protection. Specifically, the fall booster teaches B-cells (your antibody factories) how to make antibodies specifically against Omicron. This will help the first and secondary lines of immune defense. And it may ensure that protection lasts longer than the original vaccine’s did.

Prevent infection and transmission. The booster can reduce the chances of infection, at least in the first couple months. Protection isn’t perfect, but it is helpful, as it decreases your chances of getting sick and/or having to miss an event, like a wedding or seeing grandpa for Thanksgiving. This will also help avoid missed school.

Shorter duration of illness. The vaccine also shortens the duration of illness. So, for example, if you do get sick, instead of having symptoms for 13 days, you might be sick for 5 days.

Bottom line

The calculus between benefits and risks of this vaccine changes over time, but there are still significant benefits to the fall booster, even for young males. Only you can weigh those benefits with risks, but to me the story is still clear: everyone should get a fall booster.

Love, YLE

PS: ACIP meets next week to talk about COVID vaccines among children. I’m very much hoping they present an updated risk/benefit analysis. If I missed anything in this post, I’ll be sure to keep you updated.

“Your Local Epidemiologist (YLE)” is written by Dr. Katelyn Jetelina, MPH PhD—an epidemiologist, data scientists, wife, and mom of two little girls. During the day she works at a nonpartisan health policy think tank, and at night she writes this newsletter. Her main goal is to “translate” the ever-evolving public health science so that people will be well equipped to make evidence-based decisions. This newsletter is free thanks to the generous support of fellow YLE community members. To support this effort, subscribe below:

Another consideration for the risk bucket: because these vaccines are so new, we don’t know the longer term implications of taking them.

Question - how much weighting should be applied to a possible long term risk that is currently unknown but could be severe? If we exclude the “unknown future” from our cost/benefit math, we are saying “there is zero chance of any long term harm.” But in the real world, we know some things do in fact cause long term harm.

Please help me to understand why you and others write that prevention of death and hospitalization are the primary goals of the vaccine. Weren’t those secondary endpoints in the clinical studies?

Fwiw, I’m pro-vax bit have come to develop a degree of skepticism re experts who seem to reflexively paper over any concerns.

I’ve always found you to be nuanced and thus one of my main sources for info, so I ask with all respect and curiosity.