But first, Covid-19. Last week, hospitals were no longer required to share data on Covid-19 hospitalizations. However, Health and Human Services proposed a new rule requiring hospitals to continue reporting Covid-19 hospitalizations during non-emergency times. Public comment is now open. Please go HERE to provide your opinion. (My humble opinion: This is an essential system needed to protect our communities’ health and safety.)

Now, onto H5N1. A State of Affairs and your top questions answered.

H5N1 State of Affairs

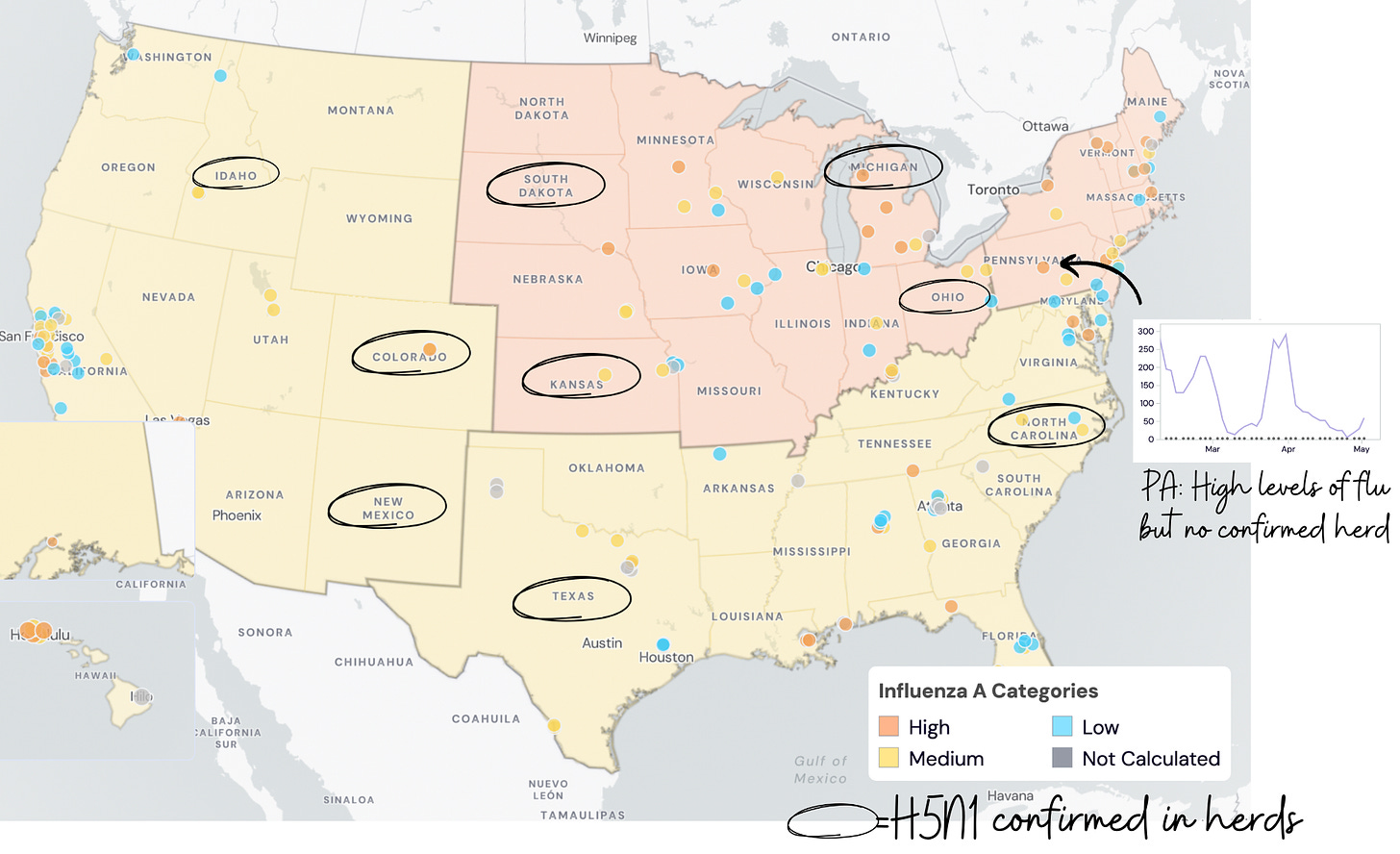

There are 36 known infected herds across 9 states. The last identified herd was on April 25. Is this fizzling out? Could be. Or, more likely, it’s continuing to spread without us knowing. Testing animals and humans is still voluntary, and asymptomatic testing is not happening.

We are flying blind.

This is nicely demonstrated in wastewater. There are quite a few areas where Flu A is “high” or “medium” in wastewater—indicating H5N1 since we are out of flu season— but where herds have not been identified. This is most likely from animals (like milk dumping), but we certainly could use more clarity on what is exactly causing the increase.

There is still just one confirmed human case. I would not be surprised if there were more undetected, though. Some veterinarians have reported that workers have symptoms on farms with sick cows but didn’t test. The good news is that we’re not seeing huge clusters of sick people in emergency departments. So, if there are more human cases, I’m pretty confident they’re mild, from direct contact with sick animals.

1. How concerned should you be?

H5N1 is taking up a lot of brain space for epidemiologists, virologists, and veterinarians alike. Alarm bells are going off, many questions are thrown around, and frustration is brewing.

Concern has percolated to the public. I tell my family and friends: H5N1 is something to watch, but for the general public, should only take up about 2-7% of your headspace.

Three reasons:

Spillovers happen all the time, but very few become pandemics because many unlucky things must occur in sequence. The probability of a pandemic in any given year is 2%; this outbreak has increased it a little (I would wager 7%).

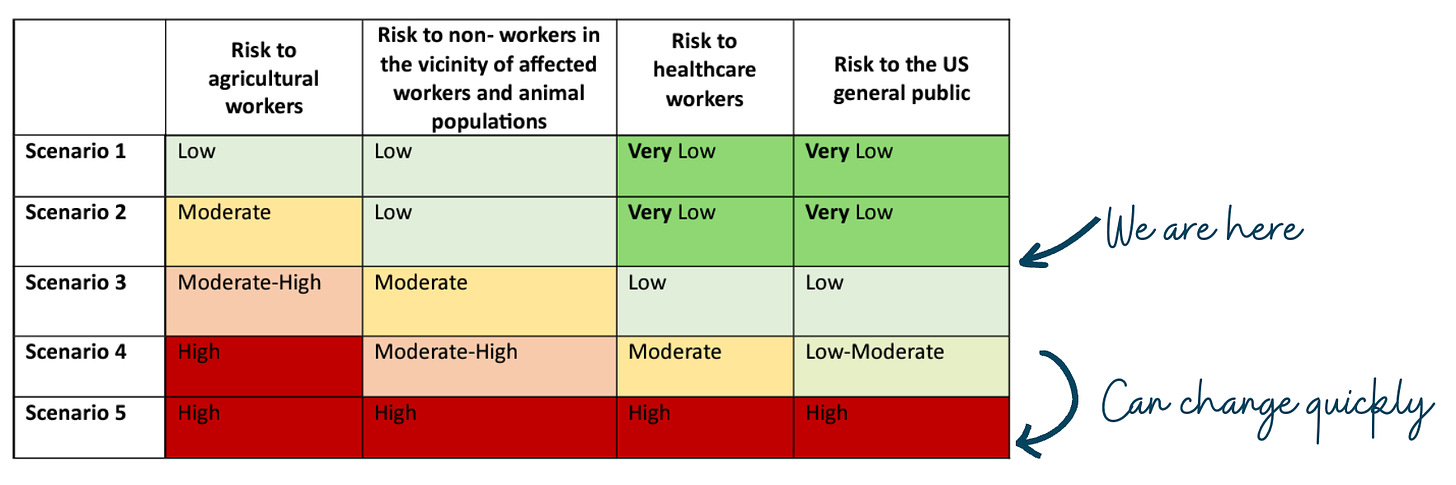

The risk to the general public today remains low. According to a risk assessment report from Dr. Caitlin Rivers’ team at John Hopkins, we are currently between risk scenarios 2 and 3 below. This isn’t March 2020—not even January 2020. H5N1 is not spreading among humans, and this virus isn’t novel; we have been studying it for years. Risk will ramp up if we see human clusters (Scenario 4) or sustained human spread (Scenario 5).

There’s not much you can do. Don’t drink unpasteurized milk. (It isn’t sold in grocery store chains, but you can find it at farmers markets, etc.) Don’t touch wild birds. And if livestock animals look sick, stay away. Call your Congressman and urge pandemic preparedness and/or biosecurity support.

We are coming off an exhausting and hugely traumatic Covid-19 emergency. Many of us aren’t psychologically or physically ready for another, but our survival sensors remain on high alert. Watching that we haven’t learned lessons from Covid-19 after all we went through is equally frustrating.

But right now, H5N1 remains a low-chance, high-consequence situation.

2. What are the symptoms of H5N1 infection?

Unless you work closely with livestock, have had contact with dead birds, or drink raw milk, it’s very unlikely that H5N1 is causing your symptoms.

Symptoms can range from asymptomatic to severe. Textbook symptoms for H5N1 are like the flu: fever, chills, cough, runny nose, etc. Some people also get red eyes because our eyes have bird flu receptors. The only symptom the Texas farmer had was red eyes (see his eyes in the picture below).

3. Can this affect my pets?

Domestic animals—cats, dogs, and backyard flocks—can get H5N1 if they contact (usually eat) a dead or sick bird or even its droppings. The current cow outbreak revealed another infection pathway: unpasteurized milk.

Cats on farms in Texas with infected cows got very sick; 50% died (presumably) from drinking raw milk.

4. How do we know that our food is safe?

FDA found dead viral fragments in milk. It sounds scary, but we have over 100 years of data on the effectiveness of pasteurization. To confirm, the FDA tried to grow an active virus from pasteurized milk samples at our grocery stores. These experiments failed, which means virus fragments detected in milk were broken pieces that could not replicate and thus could not harm humans.

They also tested other milk products, such as cottage cheese, sour cream, and beef, in grocery store products. All are safe to consume.

Don’t drink unpasteurized milk. It can make you very sick.

5. How dangerous is H5N1 to humans?

You will see a 50% fatality rate cited. Technically, this is correct because it’s listed on WHO’s website.

However, the “true” fatality rate is likely lower for three reasons:

This is among the cases detected. Past antibody studies of H5 suggest we are missing many infections.

When viruses mutate for human-to-human spread, they have to make trade-offs. Usually, this is trading disease severity for transmissibility.

We may have some cross-protection with regular flu strains. We’ve all seen N1 (the second part of H5N1) a bunch of times through flu vaccines and/or infection.

Of course, as we learned during the pandemic, even a small percentage of a large number of people is a large number. It could be devastating. So, regardless of the exact number, we need the government to prevent this from jumping to humans.

Bottom line

The H5N1 puzzle marches on. The risk to humans is not uniform. Unless you work on a farm or drink unpasteurized milk, keep H5N1 as a small nugget in your headspace. If risk changes (which it can and can quickly), at the very least, I will let you know.

In the meantime, local, state, and federal governments and key partners really need to get a handle on this so a pandemic can be prevented. The time to stop H5N1 is now.

Love, YLE

P.S. Keep those questions coming!

“Your Local Epidemiologist (YLE)” is founded and written by Dr. Katelyn Jetelina, M.P.H. Ph.D.—an epidemiologist, wife, and mom of two little girls. During the day, she is a senior scientific consultant for several organizations, including CDC. At night, she writes this newsletter. Her main goal is to “translate” the ever-evolving public health world so that people will be well-equipped to make evidence-based decisions. This newsletter is free, thanks to the generous support of fellow YLE community members. To support this effort, subscribe below:

I'm glad this is on the YLE radar. I'm not psychologically or physically prepared as a primary doc to do this all over again... but I agree this is different/potentially better in a lot of ways. However, a future mutant does have the potential for higher mortality rates than we saw with Covid.

The WastewaterScan website is amazing, and is actually helping me game out which viruses I might be seeing in my practice. URI right now near Philly? Probably metapneumovirus. GI bug? Probably rotavirus or norovirus, based on the sewage analysis downstream.

And at the risk of being self-referential I'll include a link to a post I did last week about H5N1 from my primary care angle. Always appreciate your guidance, and I hope this H5N1 continues to be a scenario 2 or lower.

https://mccormickmd.substack.com/p/bird-flu-as-seen-from-a-primary-care

thanks for the update! just to clarify— we believe the wastewater is picking up animal cases, right? NOT unchecked human spread