HHS picks, the House subcommittee report, and pandemic revisionism

Questions are important and needed, but we must not resort to rewriting history.

The Health and Human Services appointees were rounded out last week under the new Trump administration. In general, the picks largely represent two themes:

People with a history of ignoring reality, like RFK Jr., and

Voices highly critical of Covid-19 era policies.

Dr. Jay Bhattacharya, recently appointed NIH Director, and Dr. Marty Makary, appointed FDA Director, belong to the second category. Dr. Bhattacharya is a health economist, and Dr. Makary is a pancreatic surgeon and public policy researcher. Both are from reputable institutions (Stanford and Johns Hopkins), and both are outspoken and frustrated that the scientific establishment did not agree with and implement their policy positions.

These appointments came shortly before the House Covid-19 Subcommittee submitted its Final Report on lessons learned during the pandemic.

We need to look back and learn from the pandemic, but not like this

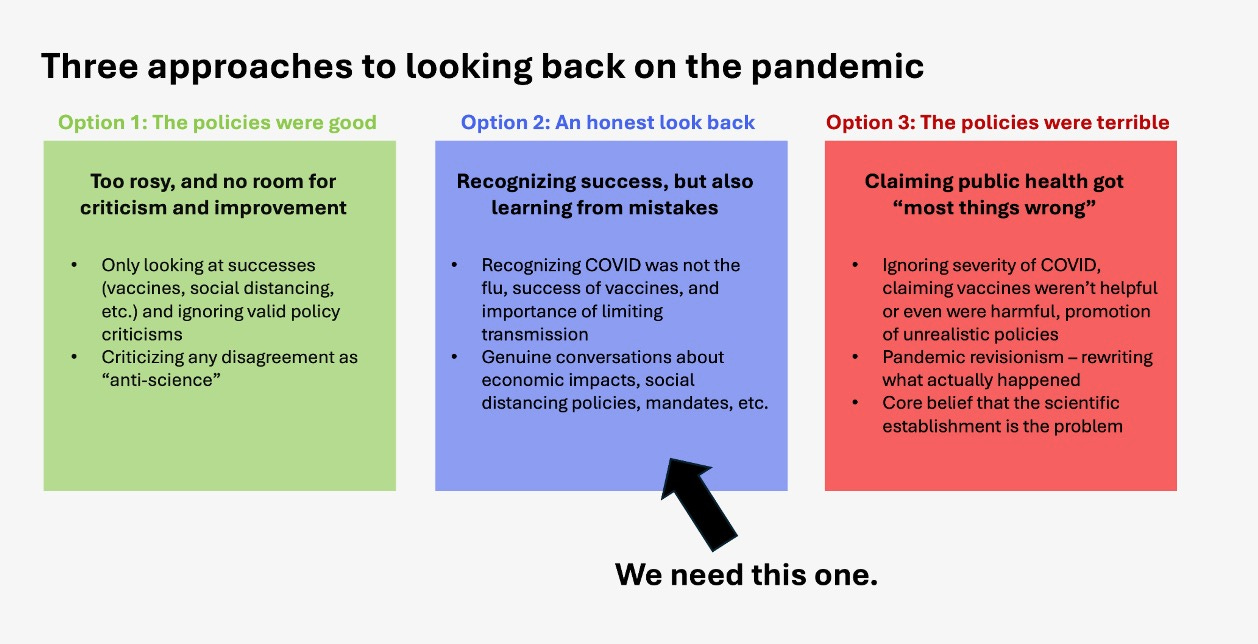

There are valid and important conversations that we need to have about pandemic policies, something we’ve tried to do here. Covid policies did not get everything right, and it’s critical we learn from past mistakes and not reject valid criticism as “anti-science.”

But some of the views championed by these administration choices and the subcommittee report indicate the pendulum swinging entirely other way towards “pandemic revisionism”—the impulse to ignore the thorny, difficult decisions we actually faced for oversimplified and/or factually inaccurate talking points.

We need an honest look back that acknowledges both successes and failures, not a rewrite of history painting the public health response as far worse than it was.

Recognizing success

Americans will be debating Covid-19 policies for the next 100 years. But we must not lose the forest for the trees. As David Wells outlined in his New York Times article, “on the most basic and essential questions about the pandemic, the public health establishment was . . . actually, right:”

Covid-19 was not the flu. It was bad, killing more than 1 million Americans. It’s still not like the flu.

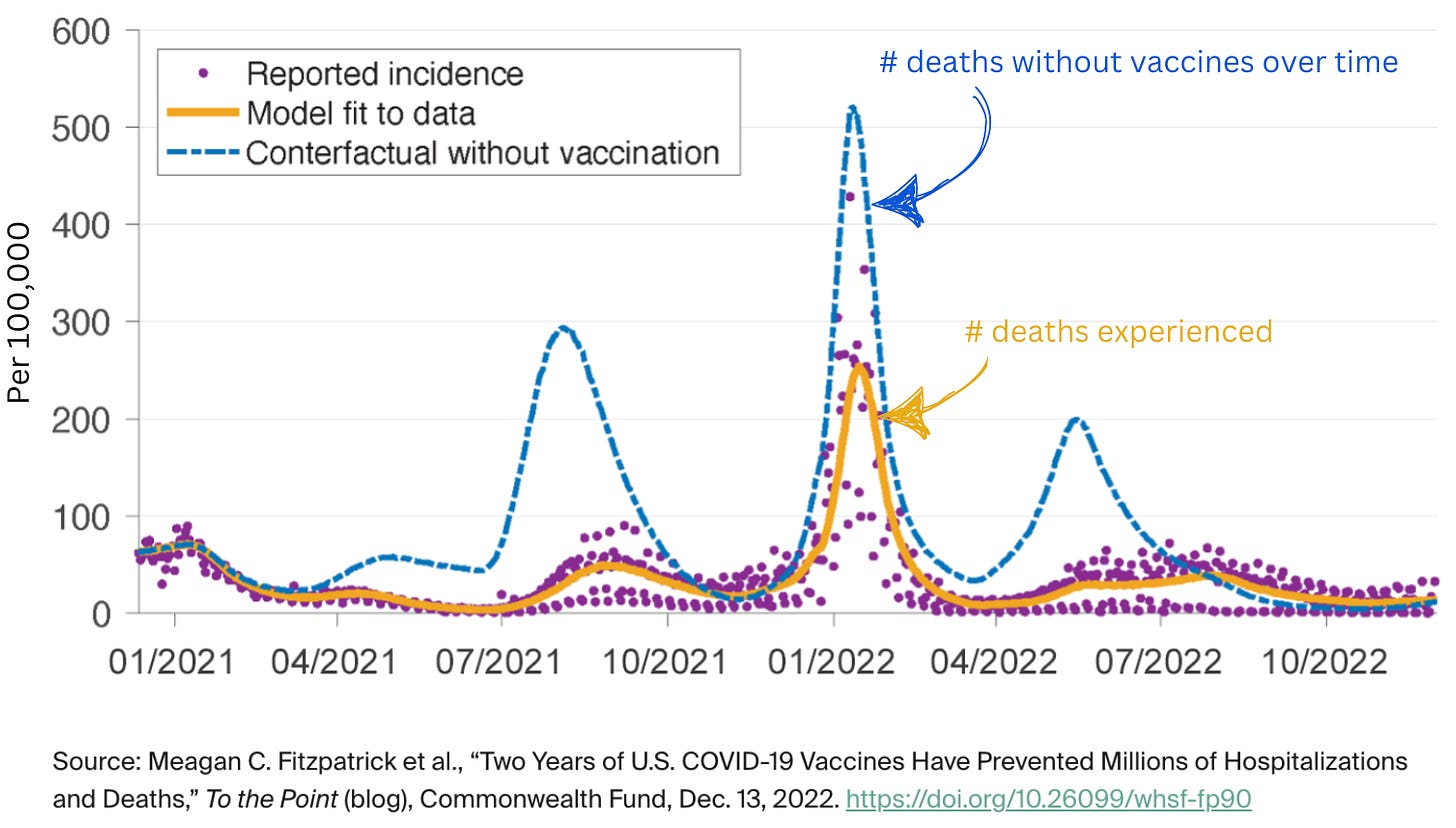

Vaccines were really good—particularly the primary series—which saved more than 3 million adult lives in 2 years and more than $1.5 trillion. This was partly due to Operation Warp Speed by President-elect Trump—getting us a safe and effective vaccine in less than 9 months.

Limiting transmission through social distancing was important before vaccines were available. In winter 2020, we were losing ~3,500 people per day. And that’s with restrictions largely in place, like working from home and eating outside, and many schools were still closed. And it worked. In fact, social distancing measures were so impactful that a common strain of influenza disappeared from the planet.

Learning from mistakes

Many pandemic health protections had benefits and harms. There were trade-offs, and discussions of those trade-offs were largely put aside, by both the scientific establishment and the critical voices pushing back.

Answering what we got wrong and why will ensure we do better in the future:

Did some states do better than others? What does “better” mean?

What steps should states have taken to mitigate the harms of shelter-in-place orders? How do we balance the risk to health versus the harms of social isolation?

What is the decision framework for closing and reopening schools in future pandemics?

The discussion has to be serious, genuine, and balanced. Refusing to acknowledge mistakes is not helpful. But pretending that most public health policies were largely failures isn’t helpful either. We must recognize the comfort of 2024 immunity and differentiate between what we got right, what we got wrong at the time (due to limited knowledge), and what we just got plain wrong.

Some of the proposed policy alternatives would have been worse

In their criticism of Covid-19 policies, alternative policies were proposed by many current HHS picks, including Bhattacharya and Makary. These positions may signal how they would handle future outbreaks, such as H5N1 if it becomes a pandemic.

However, these positions often lacked evidence, and their predictions did not bear out.

Take the Great Barrington Declaration. In October 2020, the GBD advocated for a distinct approach: isolate the vulnerable while allowing infections to spread among lower-risk members of the population. A position co-authored by Bhattacharya, the GBD claimed this approach would ultimately achieve herd immunity without the economic and social toll of restrictions. The authors of the GBD didn’t include any scientific evidence or models, and it was never peer-reviewed.

The idea went viral. Contrary to rumors that it was suppressed, the vast majority of health leadership heard about it, but very few agreed with it. A few influential people did embrace it. Trump met with the GBD authors in the Oval Office. Trump’s coronavirus czar, Scott Atlas, embraced and adopted the GBD—for example, he successfully curbed federal testing programs. The GBD advised Florida Governor Ron DeSantis.

However, the plan was fatally flawed—epidemiologically, ethically, and logically (as YLE has written before). For example, no feasible plan was provided to isolate the vulnerable effectively. Most of our elderly population cannot fully live in isolation—nursing homes require younger staff, and many grandparents live with their families, for example. Nursing homes were already attempting to isolate their residents as much as possible, and Covid was still getting in and killing people. Effectively isolating millions of elderly while a highly infectious virus burned through the population simply wasn’t feasible.

Take predictions about natural immunity. Natural immunity is complicated. We agree that public health messaging shied away from this more than it should have, leading to a loss of trust. There were many complex reasons for this lack of messaging. But Makary’s approach represented an unhelpful pendulum swing in the opposite direction—not as severe as the GBD recommendations, but inaccurate nonetheless. He repeatedly made predictions about herd immunity from natural infection that turned out to be untrue (famously predicting Covid-19 would be “mostly gone” by April 2021, shortly after which Delta killed hundreds of thousands of Americans). And he downplayed the threat of the virus (for example, calling Omicron the “omi-cold” and the alarm around it “pandemic of lunacy,” despite it ultimately killing more Americans than Delta.)

Then, take the vast majority of other topics highlighted in the House subcommittee report. Some of the subcommittee’s report contains valid criticisms (for example, the confusion created by flip-flop on masks). But many more greatly miss the nuance needed for a fair discussion of how to do better next time (the 6 ft. distance wasn’t pulled out of thin air; masks work on the individual; travel restrictions don’t work; we will likely never know for sure where Covid started.)

A common thread: the establishment is the problem

There is a lot of frustration with our systems—public health, healthcare, government, media, and more—and, in many cases, rightfully so. With our lives at stake, it’s worth critically thinking about the system, recognizing the public health infrastructure's value, and working from within to address and improve problems.

But many of the HHS picks represent an entirely different view: a belief that the establishment is fundamentally corrupt and needs to be destroyed and remade. Unfortunately, the justification for this view is often based on falsehoods, and destruction is much easier than rebuilding. As senior health leaders senior health leaders in the U.S., they will quickly find that leading and rebuilding our nation’s healthcare institutions is much harder than criticizing from the sidelines.

Bottom line

We are moving into an era that represents a rejection of the public health establishment. Change is coming, but not all change is good change. We need to have honest discussions about what went right and wrong with a focus on learning how to do better next time, not rewriting what happened.

Love,

YLE and KP

Kristen Panthagani, MD, PhD, is a resident physician and Yale Emergency Scholar, completing a combined Emergency Medicine residency and research fellowship focusing on health literacy and communication. In her free time, she is the creator of the medical blog You Can Know Things and author of YLE’s section on Health (Mis)communication. You can find her on Bluesky, Instagram, or subscribe to her website here. Views expressed belong to KP, not her employer.

Your Local Epidemiologist (YLE) is founded and operated by Dr. Katelyn Jetelina, MPH PhD—an epidemiologist, wife, and mom of two little girls. YLE reaches more than 280,000 people in over 132 countries and has a team of 11 whose main goal is to “translate” the ever-evolving public health science so that people will be well-equipped to make evidence-based decisions. This newsletter is free to everyone, thanks to the generous support of fellow YLE community members. To support the effort, subscribe or upgrade below:

“We need to have honest discussions about what went right and wrong with a focus on learning how to do better next time, not rewriting what happened.”

Precisely, thank you.

Oh, boy, this really touched a nerve!

Make no mistake, I agree completely with this post. It touched a nerve because I served as Commissioner of Public Health in a large state and the mis- and disinformation regarding our pandemic response is more than just galling, it is a national security risk.

Why?

Because the Know-Nothing "post-truth" mis- and disinformation industry that thrives in the wake of the pandemic now has numerous and loud voices who say, "All authorities are lying to you. If you're smart, you will do the opposite of what they tell you [and, continue to monetize my content]."

In these Cabinet nominations, we see a thinly veiled version of this toxic, dangerous and erroneous meme. They have advanced their careers by exploiting the post-truth algorithm.

I believe the most glaring mistake in the pandemic response can be attributed to a failure of effective Crisis Communication. I capitalize "Crisis Communication" because it is a discipline in itself. The CDC is a good place to start learning about it: https://www.cdc.gov/cerc/php/about/index.html [God Bless my colleagues at the CDC, they can be more long-winded than needs be, but it's all very worthwhile.]

Chief among the errors in Crisis Communication at the national level was the failure to make clear that the risk to society from the COVID pandemic was that it would crash our inpatient hospital system, and NOT that is was going to have a fatality rate that would rival the Black Plague. I made exactly this point when I first briefed my Governor on 01/20/2020. My Governor "got it," and never pushed back on any of the medical or public health scientific input he received from me and other experts he consulted. That's a big deal, y'all!

My state's primary strategic goal was to slow the spread of the pandemic virus - reduce its prevalence - such that on any given day, the hospitals around the state had the capacity to handle those infected individuals who needed the sort of support that only a hospital can provide. In my state, we came close to exceeding that capacity through four sharply distinct spikes spaced across the emergency phase of the pandemic.

In effective Crisis Communication, "Science" must advise, but our highest ranking elected Executive must make the decisions. That's how it should be and to be effective, that's how it must be. And, as this YLE post points out, the decisions were not easy: social cohesion itself was at stake. Decisions had to be made with all deliberate speed because delay cost lives and invited catastrophe. All this in the face of the unknown and the unknowable - without any solid QUANTITATIVE paradigm that could spit out an answer to the question of "how much of each imperfect countermeasure is enough to achieve acceptable results?" We still don't have a quantitative paradigm and the data needed to fit into the decision making of the next pandemic. And, as YLE points out, we are really not looking, either.

Alas, effective Crisis Communication did not happen at the federal level.

The onset of the pandemic could have been and SHOULD have been the sitting President's "Winston Churchill Moment" with the America people.

Imagine if your had heard something like this: "This is a serious situation and we must take it seriously. Much is at stake. In the face of this danger, I am asking [not "mandating"] that each of you do everything you can to slow the spread of this virus and give our nation the time it needs to keep our hospitals functioning and optimize our response. If we do this, we will prevail. That is the American way."

I don't know about you, but I never heard that message from the top.

BTW, the duty and authority to convey this message sits squarely on the shoulders of elected officials. Put (overly) simply, elected officials are "Somebodies," while scientists and bureaucrats (like I was) are "Nobodies" in the mind of the public. So, the elected official must lead the Crisis Communication message and state their confidence in the scientists and agencies that are advising on the science and doing the operational work, e.g., distributing a novel vaccine that requires an seamless ultra-cold supply chain.

While I'm at it, here's another key element of effective Crisis Communication: to be trusted, you must be clear about what you know and what you don't know. Prepare the public for the fact that as knowledge accumulates, guidance may change. That is a strength, not a weakness. Again, imagine if that and other key elements of effective Crisis Communication were practiced and repeated. I believe every elected official and their staff could benefit from knowing and practicing Crisis Communication principles. I mean, gosh, isn't that part of the reason we elect them?

I'll stop there. Like I said, this topic strikes a nerve with me.

Many thanks and kudos to YLE!