Oof. The amount of hate, anger, and “stay in your lane” emails and comments I got from the Texas and guns post was… intense. Gun violence is a sensitive topic (duh). But this also signaled that I’ve done a poor job explaining how public health works beyond a pandemic.

So, consider this your Public Health 101 short course, a re-introduction to me, and a preview of where this newsletter is going.

Public Health 101

Public health touches all aspects of our lives, not just during a pandemic and not just with infectious diseases. One of the greatest challenges of public health, though, is that when it works, it’s invisible. How many times have you actually thought about seatbelts? Or non-smoking areas? Or not getting measles?

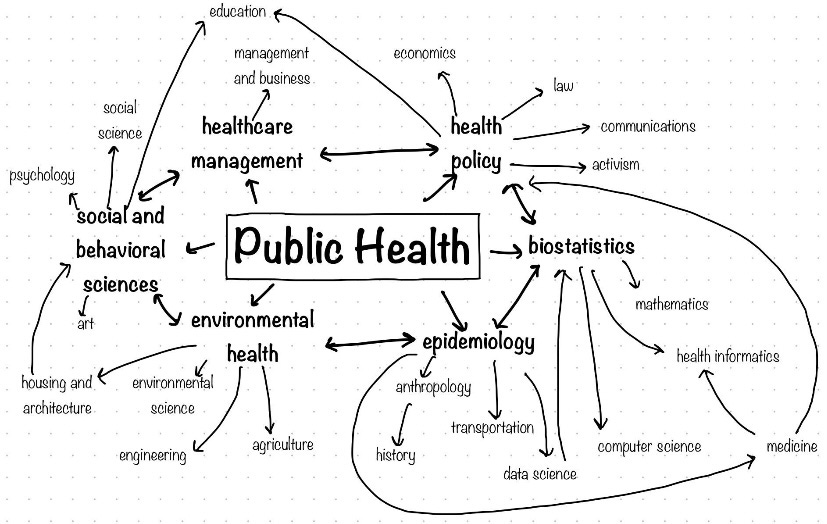

Public health touches on policy, research, and practice in areas of infectious disease (COVID-19), non-communicable diseases (diabetes, cancer), and social outcomes (food insecurity). You’ll find us in health departments, nonprofits, government agencies, academic institutions, and private industry. We are everywhere.

Epidemiology—one subset of public health—is charged with finding patterns: What predicts certain health outcomes? Because if it’s predictable, it’s preventable.

Who am I?

I am a violence epidemiologist. At least I was before the pandemic. (I’m going through a bit of an identity crisis right now.) This may surprise you given that I write a COVID-19 newsletter.

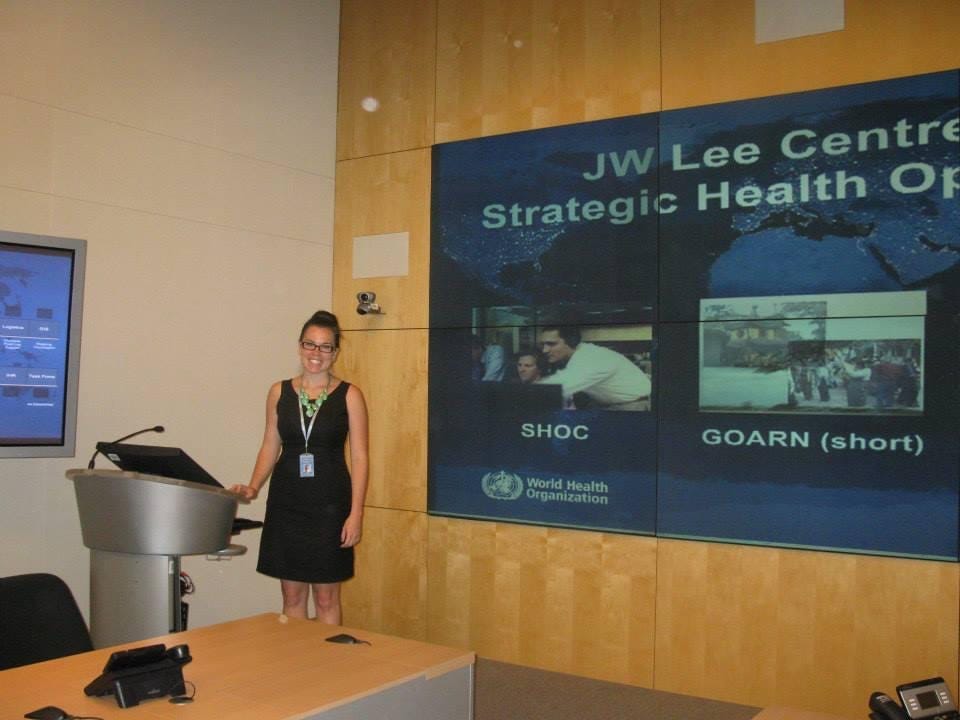

Like many epidemiologists, my initial training was in infectious diseases and data science. I worked at WHO Headquarters in Geneva, for example. I was also accepted into the EIS (Epidemic Intelligence Service) program at CDC.

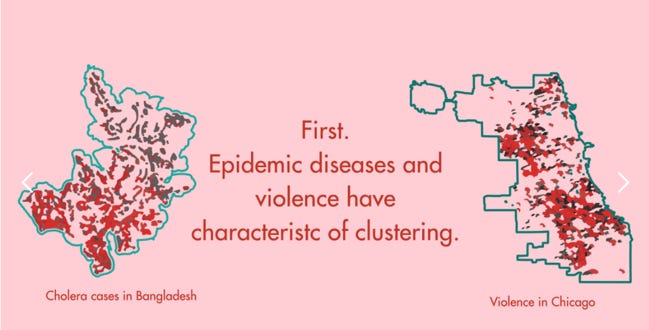

But then I slowly started applying my training to the impact of violence on health. Violence epidemiology is a fairly new field. It was born out of a case study that showed clusters of cholera in Bangladesh mirrored clusters of gun violence in Chicago. This meant gun violence was predictable and thus preventable. Since then, the field has grown to include suicide, child abuse, domestic violence, mass shootings, and much more.

In this area, I built a highly successful research lab at a School of Public Health, taught and mentored graduate students, received numerous grants, published more than 80 peer-reviewed articles, and had a very messy office.

Then the pandemic hit. And epidemiologists were thrown into an all-hands-on-deck response. We had the foundational expertise to help, even if we didn’t focus on coronaviruses. I found myself at the forefront of the response. I was also thrown into this world of knowledge translation and scientific communication (i.e. YLE). This is where I found my superpower.

Future of this newsletter?

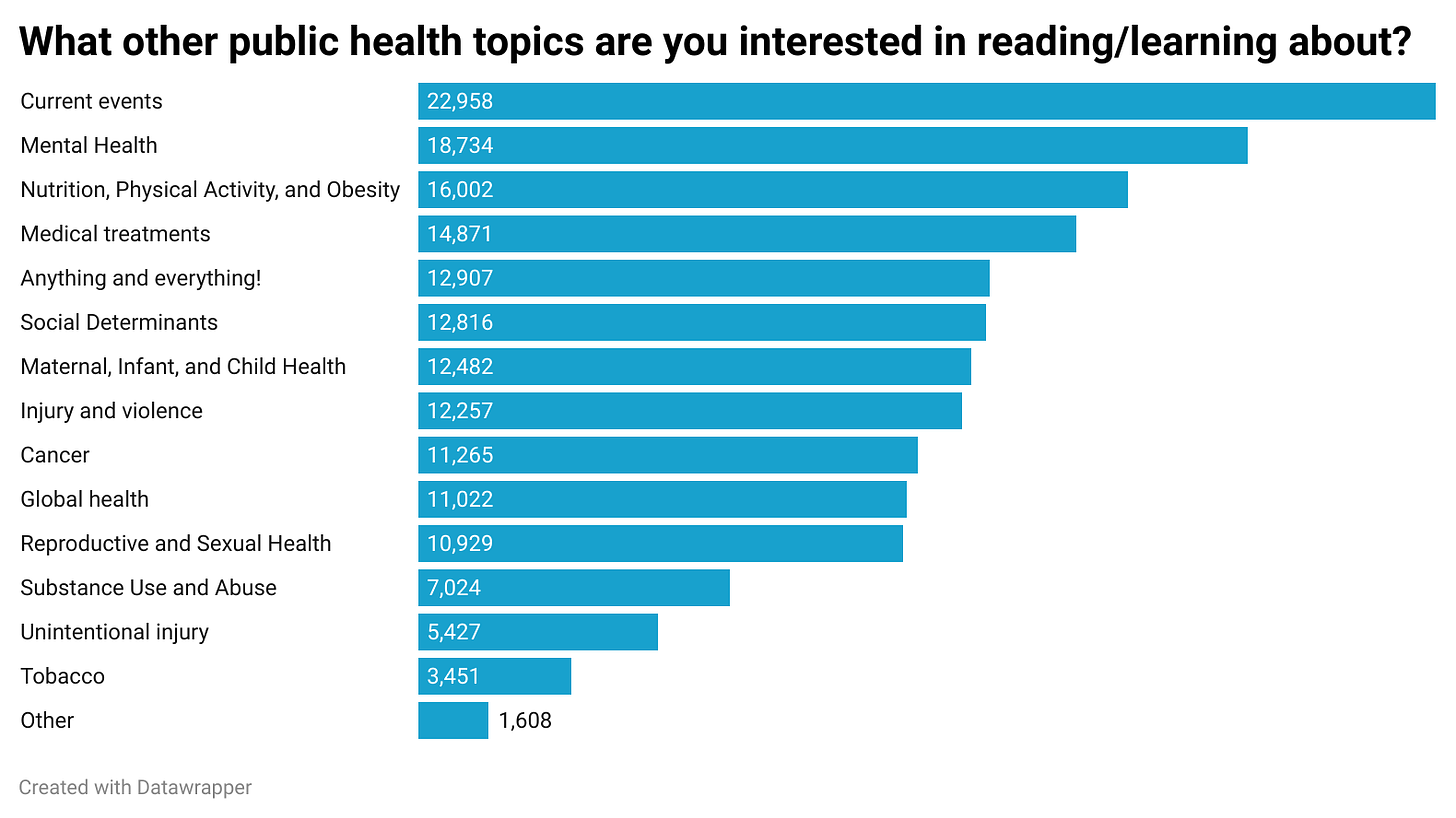

YLE will still closely follow COVID-19. But, thanks to your feedback, this newsletter will address other pressing public health topics, including gun violence.

You’ll find that, on many topics, I know very little; I am not an expert on everything. So, I have started to loop in experts I admire. In these instances, my job is a “translator”—scientists are generally terrible at speaking in plain language.

Bottom line

Gun violence is absolutely in my lane. It is absolutely in the lane of public health. In fact, public health touches on many lanes of your life. We can all make better evidence-based decisions inside and outside of a pandemic. I hope you enjoy this ride with me!

Love, YLE

P.S. To choose what topics land in your inbox, click HERE.

“Your Local Epidemiologist (YLE)” is written by Dr. Katelyn Jetelina, MPH PhD—an epidemiologist, data scientist, wife, and mom of two little girls. During the day she works at a nonpartisan health policy think tank and is a senior scientific consultant to a number of organizations, including the CDC. At night she writes this newsletter. Her main goal is to “translate” the ever-evolving public health science so that people will be well-equipped to make evidence-based decisions. This newsletter is free thanks to the generous support of fellow YLE community members. To support this effort, subscribe below.

Please keep up the great reporting on ALL Public Health Issues. Data Rules.

Is there a public health sector that studies hate and anger? I'd like more information on that epidemic.