Vaccines will help control the monkeypox (MPX) outbreak. The bad news is that we desperately need more doses. And we don’t know how much the vaccines help and in what manner they help (prevention, duration of disease, severity of disease). This information is absolutely essential so people know how well they are protected and what behaviors they should (or should not) change. This information will also have major implications for controlling the outbreak worldwide.

How effective was the second generation vaccine against MPX?

The CDC website states the smallpox vaccine is 85% effective in preventing MPX among humans based on data from Africa. From what I can tell, this is based on a 1988 study in the Democratic Republic of the Congo. Scientists looked at a pretty big sample (3,686 people) who were exposed to close contacts of MPX. Among people who were exposed and then infected, 15 were vaccinated and 54 were unvaccinated. This equates to an efficacy of 87%, which is great news! At least for the historical outbreaks.

The problem is that the virus has mutated, it’s spreading very differently than before, and it’s been a long time since people got this smallpox vaccine. So we cannot assume a smallpox vaccination from decades ago will act the same way during this outbreak.

How effective is a smallpox vaccine from decades ago?

A very recent study published in the Lancet collected data on 181 patients with an MPX infection in Spain during the current outbreak, including data on whether people had a previous smallpox vaccination. Among the 181 MPX cases, 32 (18%) had a history of the smallpox vaccination. We cannot calculate efficacy because we don’t know how many people were exposed and not infected, but overall this was not great news. We need to better understand the protection provided in the context of the current outbreak, like investigating the duration of protection and why vaccine effectiveness may have changed.

How effective is Jyennos?

We have more than 22 clinical trials of Jyennos… against smallpox. This means we know it’s safe, but we don’t know how effective it is against MPX. A few years ago, the FDA approved the vaccine for monkeypox by relying on survival data from primate studies. (Far more primates survived after vaccination compared to those without vaccination.)

But this is really all we have to go on for the current vaccine rollout.

Scientists are smartly collecting data during the rollout, though. For example, a French preprint study followed 276 people who received a shot after a high-risk contact. Ten people developed MPX quickly thereafter (which is not surprising as vaccines need time to be effective). But two people were infected at 22 and 25 days after vaccination, which was unexpected. This means that the vaccine is not perfect at preventing infection after close contact. We certainly need more data.

We hypothesize that even among those who get vaccinated and infected, the vaccines still help reduce viral load and, thus, severity of infection. We have yet to see the clinical data on that yet, though.

How effective are other innovative strategies?

Because of suboptimal vaccine supply in the U.S., we are forced to think innovatively about how to broaden the vaccine reach during this public health emergency. As a result, we are trying two methods, but they leave us with even more questions:

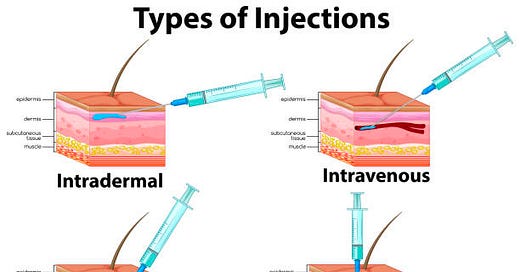

Intradermal vaccination. Earlier this week, the FDA authorized intradermal vaccination, which means administering the vaccine at the top layer of our skin. The skin is home to a number of immune cells that trigger a potentially better immune response and requires less vaccine liquid (we could get five vaccines with this new strategy compared to one with the subcutaneous route). This strategy has been used in other emergencies, like Ebola. But we only have one study showing this works for the smallpox vaccine. In 2015, scientists randomized 524 people to test vaccination using this method and showed it was effective. When we use this method with other vaccines (flu and rabies), there is also significant skin irritation. We don’t know if that will be the case with this vaccine. Implementation is also going to be difficult, as it requires special training and confidence. How much will this impact effectiveness or uptake? We don’t know.

Dosage sparing. Some jurisdictions, like New York, are also spacing the dosing. So, people get the first dose (the regular subcutaneous* route) and then have to wait until we get more vaccines in the fall for the second dose. This increases reach, but the protection after one dose is unknown.

Given the (limited) evidence, vaccine shortage, and urgency of this emergency, I support these approaches, as long as people understand that this is experimental and we collect data along the way to make better, data-driven decisions in the future.

Bottom line

We really need real-world effectiveness studies on MPX vaccines. This will be coming. In the meantime, we have to make difficult policy decisions based on limited data. (Sound familiar?) But we cannot repeat our COVID-19 mistakes and provide a false sense of security with vaccines. Communication around scientific uncertainty and how it’s being used to make decisions needs to be at the forefront so we can build trust and effectively dampen the outbreak across the globe.

Love, YLE

*A previous version of this post incorrectly said the regular route is intramuscular, but it’s in fact subcutaneous

“Your Local Epidemiologist (YLE)” is written by Dr. Katelyn Jetelina, MPH PhD—an epidemiologist, biostatistician, wife, and mom of two little girls. During the day she works at a nonpartisan health policy think tank, and at night she writes this newsletter. Her main goal is to “translate” the ever-evolving public health science so that people will be well equipped to make evidence-based decisions. This newsletter is free thanks to the generous support of fellow YLE community members. To support the effort, please subscribe here:

Will you write a follow up on monkeypox testing? Obviously, testing is a key component of controlling the spread. I know there are saliva tests you can order by mail and lesion tests that can be conducted at a clinic. I have also read many reports of people finding it difficult to get tested. I’d love a report from you.

With respect, Dr. Jetelina, I think you are asking the wrong question. As you well know as a world-class epidemiologist/ID person, vaccination is but one part of pandemic control. I have every confidence (sadly) that our country will mess up the rest of the public health strategy for control of a pandemic just as we did with COVID-19. Hope I am wrong...but