Harvard invited me to review a new book, Within Reason, by Dr. Sandro Galea. I don’t personally know Dr. Galea, but this has to be one of the most impactful books I’ve read yet. It forces reflection (As I say below, “It was like being forced to look in the mirror after a war”). But more importantly, I hope this book will ignite a critically important debate in public health. Go get the book. Please send me your thoughts *after* you read. I’m eager to hear them.

Here is my review, originally published in Harvard Public Health Magazine.

If the pandemic taught us one thing, it’s that public health must be reimagined for the 21st century. Although there were major success stories, like saving more than three million lives with vaccines, the fragmented, underfunded, and inequitable U.S. public health system was cracked wide open for all Americans to see. And it wasn’t pretty.

Within Reason, written by Sandro Galea, dean of Boston University’s School of Public Health, names another uncomfortable dimension of the pandemic: Public health—traditionally a very liberal field— took a turn towards illiberalism. A liberal perspective means considering different points of view, celebrating differences, and remaining open to the possibility of being proved wrong. Conversely, illiberalism stifles debate and minimizes dissenting views.

In a three-part book of short essays compiled from his blog, The Healthiest Goldfish, Galea enlists many examples to substantiate his viewpoint: the field’s propensity to communicate with certainty in the midst of so much uncertainty (think cloth masks); the perils of groupthink; and public health’s tendency to favor pragmatic paternalism by, for example, keeping nursing homes locked down after vaccines were available.

These tendencies are perhaps understandable. During an emergency, time costs lives. The height of the pandemic happened amid incredible political instability, disinformation, and outright hostility towards public health workers, all of that sanctioned by political leaders. (Polarization affected public health, too.)

But Galea argues that if we continue on this path, the public health field will continue to lose trust among Americans. This means our efforts to combat infectious diseases and other health threats will have less impact, and communities will pay the price, with increasing morbidity and mortality.

As an epidemiologist, I found this book hard to read. It was like being forced to look in the mirror after a war, still bathed with the blood, sweat, and tears of the pandemic. To be clear: I agree with many of Galea’s points. I’ve made (and admitted) to many of the mistakes he outlines, like dismissing new pieces of information because of politics rather than evidence. And we, in public health, need to recognize these mistakes. I appreciated Galea’s approach to balancing the fine line between constructive criticism, hope, and action.

I disagree with some details in this book, though. For example, Galea implies that many in public health were wrong to push back so fiercely on ideas like the Great Barrington Declaration—an open letter that advocated for isolating the vulnerable while allowing infections to spread among lower-risk populations before vaccines were available. Given the epidemiological, logistical, and ethical concerns about this approach—especially coming, as it did, before widespread access to COVID-19 vaccines—we needed experts to push back, not automatically embrace that approach.

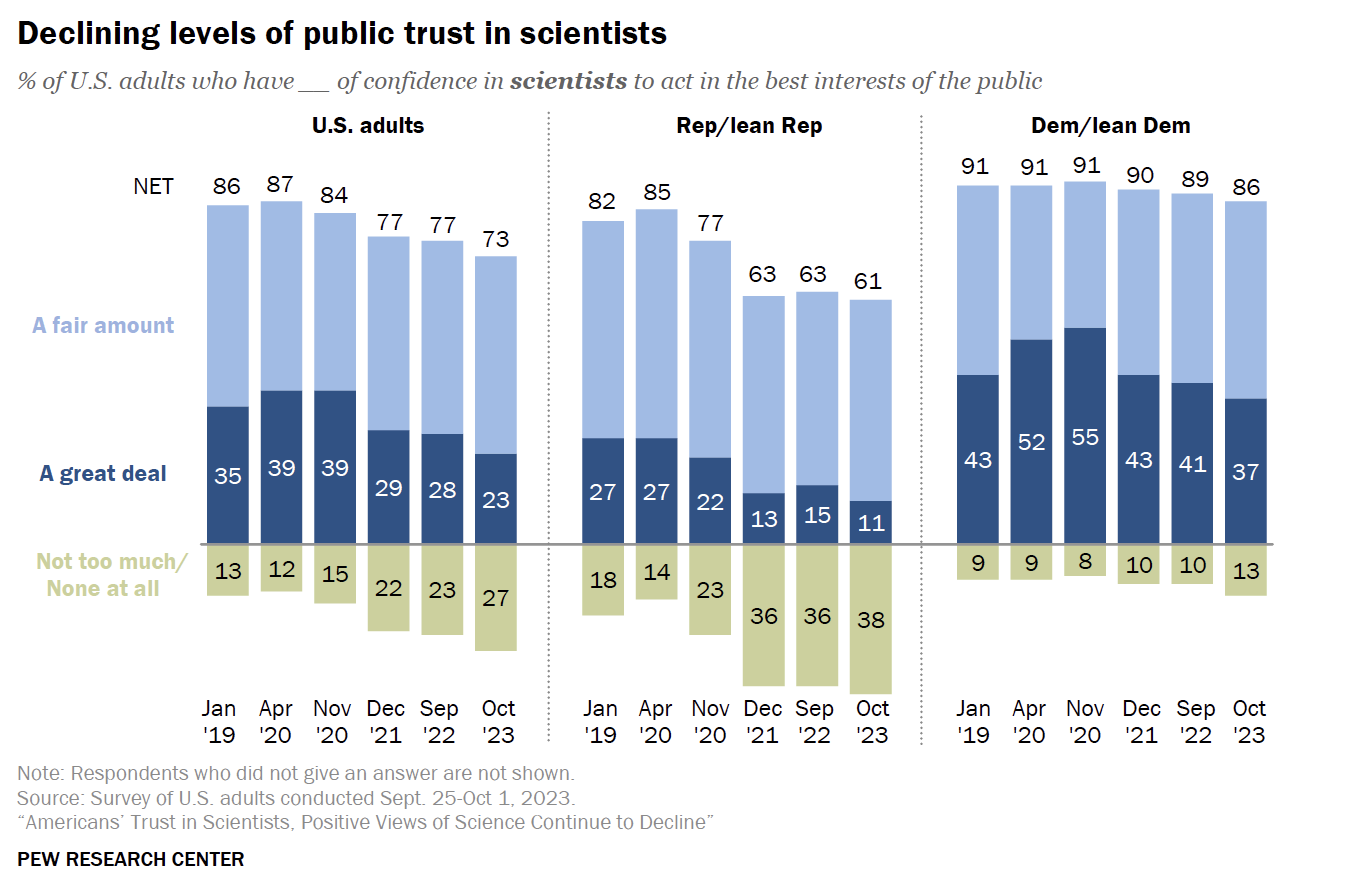

Also, this book mostly circles around the loss of trust from one group: Republicans. And rightfully so. A new poll from the Pew Research Center shows trust in scientists has rapidly declined among Republicans. Not so with Democrats. But my quibble is: Why, and more importantly how, should public health privilege one group’s information and health needs over another? How should public health balance an increasingly individualized society, given public health is about serving the greater good? These are tough questions to answer.

I presume many people in public health will feel the same way about the book: Some things we agree with, some are hard realities to face, and some things we disagree with. But I think Galea’s book will stir up the conversation in needed ways. In a healthy society, a tug-of-war between the values and morals that anchor public decision-making is not only expected, but also needed to advance and improve.

Galea provides tangible solutions on how to return to public health’s liberal roots, with a roadmap that focuses on human connection and communication: Keep an open mind; do rather than say; speak with humility; act pragmatically according to the data; get better at weighing trade-offs. But most of all, listen. Engage in dialogue about what solutions are possible. Test ideas with outside feedback. Look beyond biases that blind us. Be open to rigorous and even heated debates. Relinquish power.

At the heart of the book is a critical question: What does public health look like in the 21st century? This is a question for every one of us—for those of us working in public health, critics of public health, those in medicine; and, most importantly, for everyday people affected by public health decision-making. In an increasingly politicized environment—amid an information landscape that rewards outrage, not thoughtful consideration—and with new health threats emerging faster due to climate change, figuring out an answer is crucial but far from easy.

Thankfully, as Galea writes, “Public health is by nature forward-looking.” And we are at an inflection point. We must learn. We must strive for hope.

Millions of lives depend on it.

“Your Local Epidemiologist (YLE)” is written by Dr. Katelyn Jetelina, MPH PhD—an epidemiologist, wife, and mom of two little girls. During the day, she is a senior scientific consultant to several organizations. At night, she writes this newsletter. Her main goal is to “translate” the ever-evolving public health world so that people will be well-equipped to make evidence-based decisions. This newsletter is free, thanks to the generous support of fellow YLE community members. To support this effort, subscribe below:

Story time (related to public health, but not necessarily to this post): a child vomited in my 9-year-old daughter's class yesterday. For whatever reasons I don't understand (and I assume they are valid), the child stayed in the classroom. My daughter chose to go to the nurse and request a mask, then decided to bring the whole box of masks back to share with the class. Many of the children accepted her offer. This blew my mind- she clearly learned something about the value of public health and that we don't just have to accept catching a nasty virus for no good reason. While her greatest strengths are in writing and communication, this morning she suggested that maybe someday she will study virology (my grad school field and forever passion) to "work on vaccines for noroviruses" (her words). While many were digging in their heels, crumbling, caving, and letting fear and politics guide their choices or obstruct their better judgment in the height of the COVID-19 pandemic, some were learning, growing, and being inspired to do well by others.

One of the biggest problems with public-health messaging in the US is that it speaks to the lowest-common denominator. We saw this with masks/COVID: we were initially told masks didn't work not because the experts thought they didn't but because they didn't want people to run out and buy up all the PPE. We also see this with things like vaccine timing: "Get your flu shot whenever you can" rather than "Get your flu shot in mid-to-late-October." "Get your COVID booster anytime" rather than "Waiting at least 6 months to get a booster after an infection will improve efficacy."

Until public-health experts tell the nuanced truth regardless of how they think it will impact action, including admitting when the answer is "we don't know," nothing will change.