Earlier this year I wrote a four-post series on long Covid: burden; impact on specific health systems, like the heart; long Covid among kids; predictors of long Covid and treatment. Today’s newsletter is meant to be an update—I’m picking up where I left off, so I highly recommend reading those first, if you haven’t already.

The individual risk of death from a COVID-19 infection is now close to the flu thanks to vaccines, immunity, and treatment. However, death is not the only outcome of SARS-CoV-2. Long Covid—or the persistence of symptoms after an infection beyond three months—is still a threat to living a healthy and prosperous life.

Overall burden

A recent study pooled more then 54 long Covid studies (which included a total of 1.2 million people) and found that 6% of individuals who had symptomatic SARS-CoV-2 infection experienced long Covid in 2020 and 2021. This is consistent with a massive study in Sweden (2020-2021) that found the proportion receiving a long Covid diagnosis was 1% among individuals not hospitalized for their COVID-19 infection, 6% among those hospitalized, and 32% among those treated in the ICU.

Today, the U.K. estimates that 3% of the general population has long Covid. In the U.S., the population-level burden of long Covid has been historically difficult to grasp. But in August 2022, the U.S. Census Bureau added four questions about long Covid to its Household Pulse Survey. What did they find?

16 million working-age Americans (aged 18 to 65) have long Covid today. This equates to ~8% prevalence.

Of those, 2-4 million are out of work due to long Covid.

The annual cost of lost wages is ~$170-$230 billion a year.

The prevalence of severe long Covid is unequally distributed across race/ethnicity and age.

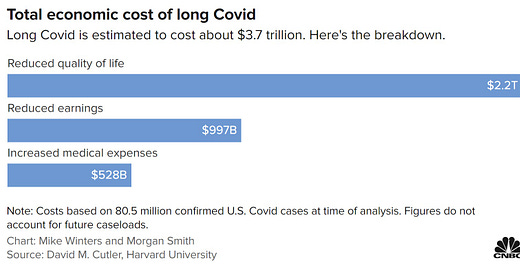

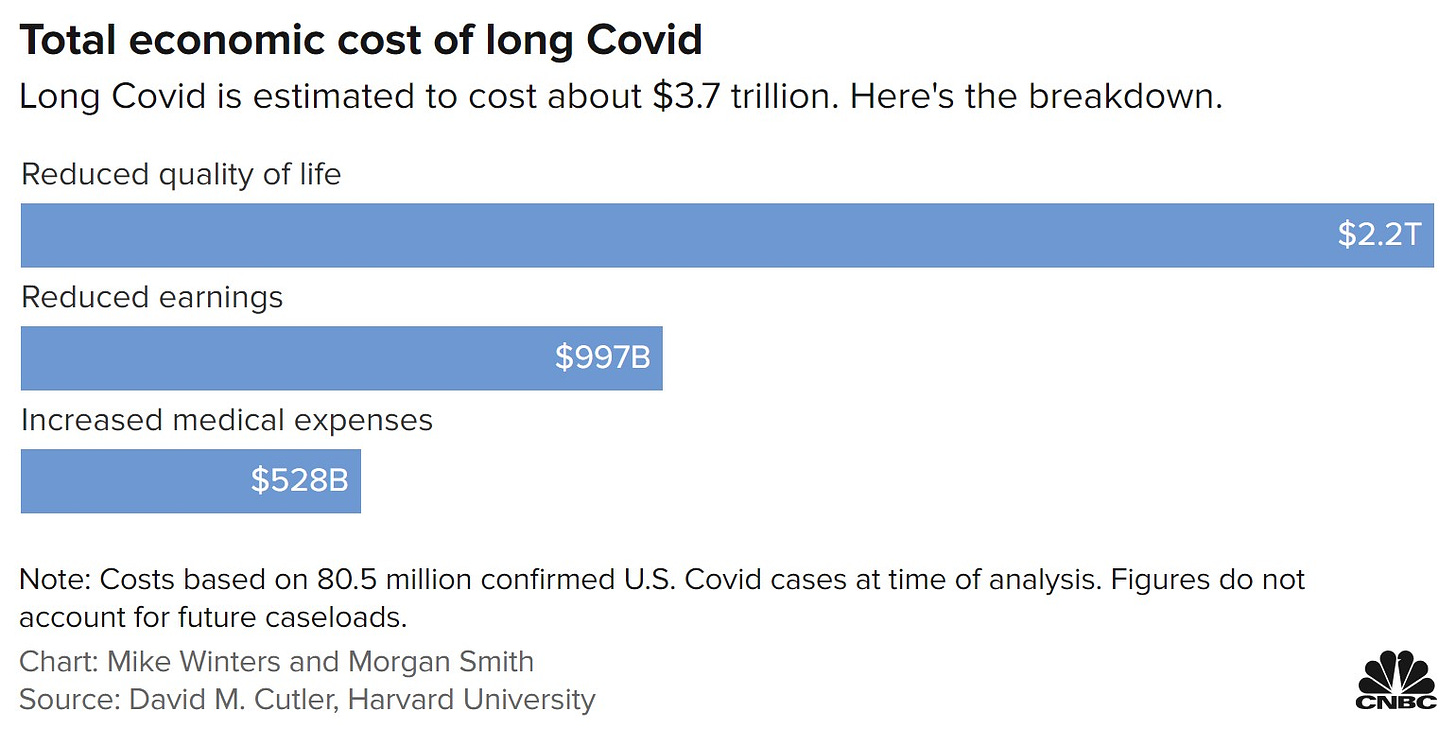

Economically, long Covid is a big deal to this country. The total economic cost is $3.7 trillion in the U.S., without accounting for future cases.

Changing risk

Just like the risk of death, the risk of long Covid appears to have changed over time.

In general, there are three things that are decreasing the risk of long Covid today:

Vaccines. A number of studies show vaccines reduce the risk of long Covid. The problem is that these studies greatly vary in the estimated reduction: some say vaccines reduce long Covid by 85%, others say 15%. The “truth” is likely somewhere in-between.

Paxlovid. One study found Paxlovid reduced the risk of long Covid by 25%.

Omicron. A very strong study in the Lancet found the odds of long Covid after an Omicron infection were significantly lower compared to after a Delta infection.

All of these help, but are not bullet proof.

Of course, the more the virus mutates to become more contagious, the risk of infection (and thus long Covid) increases.

Death from long Covid

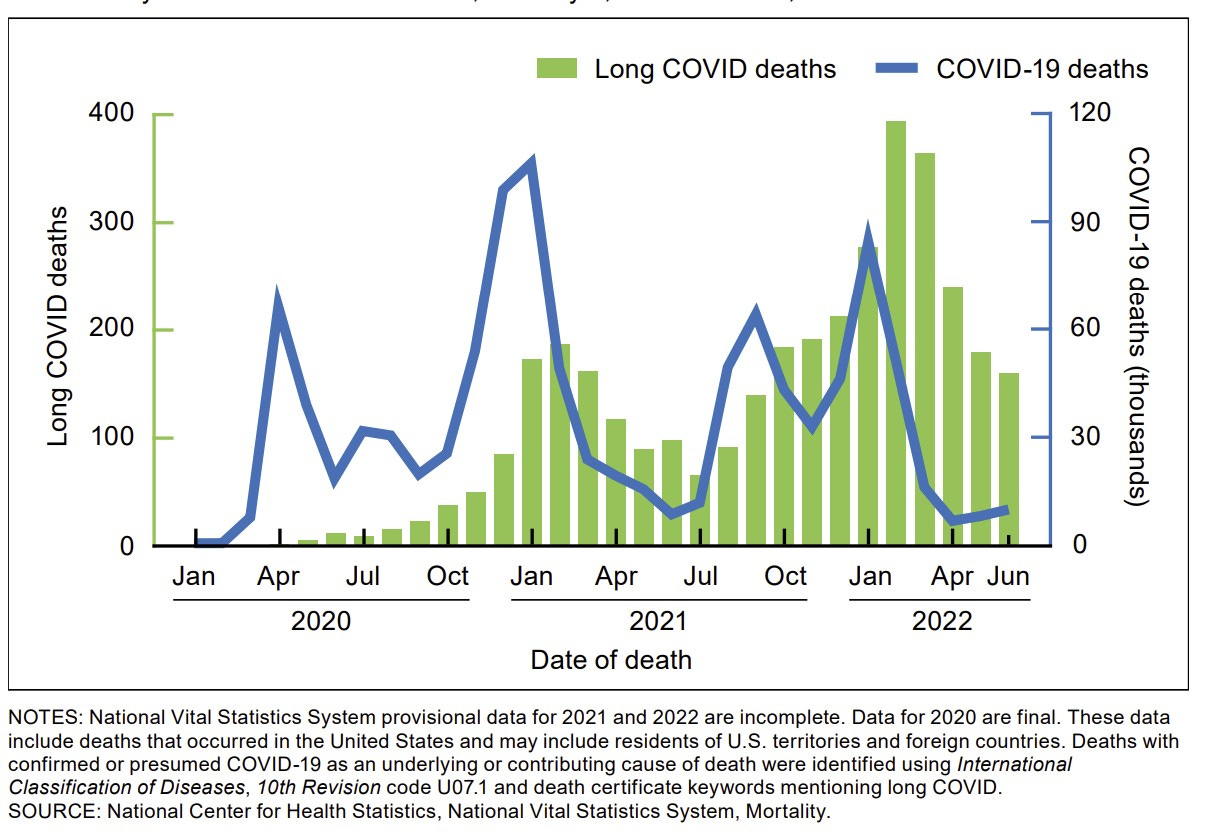

The National Center for Health Statistics released the first long Covid mortality report yesterday. The scientists started with over 1 million death certificates dated from January 1, 2020 to June 30, 2022 that indicated COVID-19 as the underlying or contributing cause of death. Then they searched for clues that the patient had long Covid by looking for words like: “chronic COVID,” “long COVID,” “long-haul COVID,” or “post-COVID syndrome.” What did they find?

3,544 deaths—or 0.3 percent of the total—had text on their death certificates about long Covid

Long Covid peaked in June 2021 (1.2%) and in April 2022 (3.8%)

Long Covid death rate was highest among adults aged 85+, non-Hispanic American Indian or Alaska Native people, and males.

A simple search of words like this has major limitations, so we cannot make causal claims. This is more of an exploratory analysis to see if “long Covid” appeared on death certificates. My hunch is that this is a huge underestimate of long Covid deaths, but it could be an overestimate. More work needs to be done.

Increased death from SARS-CoV-2 is not limited to acute illness

We are at the mercy of time to see the impact of SARS-CoV-2 infection beyond symptoms, for example blood clots.

One rattling study in the Lancet found that people infected with SARS-CoV-2 had more than 3 times the risk of dying over the following year compared with those who remained uninfected. For COVID-19 cases aged 60 years or older, increased mortality persisted until the end of the first year after infection, and was related to increased risk for heart and/or respiratory causes of death.

An Australian report of excess death found something similar.

A report from Singapore also found an increase in excess mortality after infection (people without recent infections had no additional excess deaths), however it was not linked to cardiovascular events.

Implications

On a population level, it’s clear that the footprint of SARS-CoV-2 will extend for decades to come. But what this looks like is highly debated, and there are two camps of scientists:

One camp thinks long Covid will be a mass debilitating event that will define the economies of countries for decades

The second believes long Covid is real, incredibly debilitating for the people who have it, but, given the change in risk, will not be such a big event that our future economies or health systems will fail.

Time will tell.

On an individual level, assessing risk of long Covid is extremely difficult. How much should long Covid impact my daily decisions? To me, it’s easiest to understand a new threat by comparing it to familiar threats, like driving. I did this using MicroMorts a few months ago, comparing the risk of dying from COVID-19 to, for example, skydiving.

Here is what I found (keep in mind these are super rough estimates):

Driving: The annual risk of getting into a car accident is 1 in 30 per year for the average driver. Of those accidents, 43% are likely to be injured. And, of those injured, 10% are permanently impaired. So, the annual risk of permanent impairment from driving is 1 in 700.

Long Covid: The risk of getting an Omicron infection (asymptomatic and symptomatic) per year is ~1 in 2 (before Omicron it was ~1 in 4). If we take into account 3% of infections lead to long Covid and, of those, ~18% will have disease so severe that they are unable to work. So, the annual risk of severe long Covid (unable to work) is 1 in 370.

Other annual risk comparisons:

So, the risk of debilitating long Covid is double the risk of permanent impairment from driving. Risk of debilitating long Covid is much higher than getting injured during a house fire and about the same as getting a serious dog bite.

Of course, individuals can do a lot of things to reduce risk for all of the above: Wear seatbelts. Drive less. Make sure your fire alarms work. Don’t approach growling dogs. But, we also make conscious (or non-conscious) decisions to increase risk: texting while driving; unplugging the annoying beeping fire alarm. It’s an every day balancing act. But, just like speeding tickets, required fire exit signs, and leash laws, there are policy level initiatives that could help with long Covid, too.

Bottom line

Long Covid is an incredibly debilitating disease and millions are suffering. While risk is changing, we don’t know what the future will hold.

This leaves us with a difficult balancing act. I find myself not willing to take risks in some instances, and more willing in other instances—as with many things I do in my daily life, like driving. A person next to me will be very different. I think it will be years until this calculated decision-making becomes easier.

Love, YLE

“Your Local Epidemiologist (YLE)” is written by Dr. Katelyn Jetelina, MPH PhD—an epidemiologist, data scientist, wife, and mom of two little girls. During the day she works at a nonpartisan health policy think tank and is a senior scientific consultant to a number of organizations, including the CDC. At night she writes this newsletter. Her main goal is to “translate” the ever-evolving public health science so that people will be well equipped to make evidence-based decisions. This newsletter is free thanks to the generous support of fellow YLE community members. To support this effort, subscribe below:

This particular piece of writing needs to be an op-ed in major new outlets!

Every time I read one of your entries, I am reminded of how gifted you are at capturing the nuance in risk assessment that is so important for moving humanity forward with COVID's presence in the world. It's not binary--there is way more gray than black and white.

You are a gifted communicator, with an ability to convey complexity and--with a topic as polarized as covid responses--evaluate subjectively without judging others. I wish more people had access to and took the time to read your stuff, especially stuff like this.

"The individual risk of death from a COVID-19 infection is now close to the flu thanks to vaccines, immunity, and treatment.” Hey Katelyn, that’s not quite right in my opinion. The last numbers I saw from the CDC were 468 deaths a day or about 170,000 a year. Even if you look at the roughly 300+ it was averaging before the recent bump up, it would be near 110,000 a year. The CDC site showed the average deaths per year from flu in the 10 years prior to COVID, was about 30,000 with the worst of those years being 51,000. Don’t hold me precisely to those numbers but I am pretty sure I have them about right.By my arithmetic that means the “current” (468) COVID death rate is more than triple the risk of flu in its worst year and five and a half times the average flu rate. Using the lower number of 300 for COVID, of the last month or two, then the comparable relationships are over two, and about three and a half, times the numbers of flu deaths. I think that’s a lot more risky - not “close to". I make such a point of this because (1)for a long time I have been using that relationship as a benchmark for when I’d give up my extreme precautions and try to live a “normal” life again. I figure I could handle two times. I am older and thus the the death rates are doubtless higher in my bracket for both diseases, but, if the numbers are both understated than the relationship probably roughly holds and (2) I have seen/heard your comment or ones similar to it often enough to be bothered by it, since I think it makes light of what I consider to be justifiable cause for my (“paranoid") relatively extreme precautions.

PS Notwithstanding the above difference in opinion - one person’s “close to” can be another’s “much more” - I continue to respect, admire and appreciate the great work you are doing in communicating/educating us all.