This week I’m diving deep into long COVID. This mini-series is 5 posts in total: burden, impact on specific organs, kids, predictors, and potential treatment. This is post #3 of the series.

Long COVID among kids is one of the pandemic’s biggest mysteries—and one that causes a lot of worry for parents. This is a deep dive into what we know (and do not know) right now.

Burden

Grasping the burden of long COVID among kids has been incredibly challenging. This is, in part, for the same reasons it’s been difficult to grasp in adults (inconsistent definitions and/or lack of comparison groups in studies). But kids add other layers of complexity:

Inability to verbalize: Children, especially infants and toddlers, can’t always verbalize what they are feeling. Because we don’t have a diagnostic test, like a blood test, for long COVID, we are highly dependent on self-reporting and/or parents picking up on symptoms/different behaviors.

Inconsistent manifestation of symptoms. Symptoms can manifest differently in young children. For example, fatigue can appear as hyperactivity for some children, while other children will show sluggishness. This inconsistency makes it difficult for parents to detect the problem in the first place.

Small sample size. In the beginning of the pandemic, infections among children were far less common. Fewer infections meant fewer opportunities to evaluate long COVID. This is changing rapidly.

Nonetheless, many, many studies have attempted to estimate burden. But, to me, only seven are rigorous enough to mention because they compare symptoms among children with a COVID infection to symptoms among children without COVID infection. This removes many biases and gives a clearer picture as to whether SARS-CoV-2 truly leads to long COVID among kids.

Five of those seven studies found an incidence of long COVID ranging from 1-14% (here, here, here, here, here) and two studies reported an incidence of 0%—no difference in symptoms among children with an infection compared to children without a infection (here, here). All of these studies were among unvaccinated children. We hypothesize that vaccinations will reduce the risk of long COVID among kids, like we are seeing with adults.

The U.K. officially reports 1.0% of 5-11 year olds and 2.7% of 11-17 year olds are experiencing symptoms for at least 12 weeks. (It’s important to note that U.K. estimates are among all children, not just those who were infected).

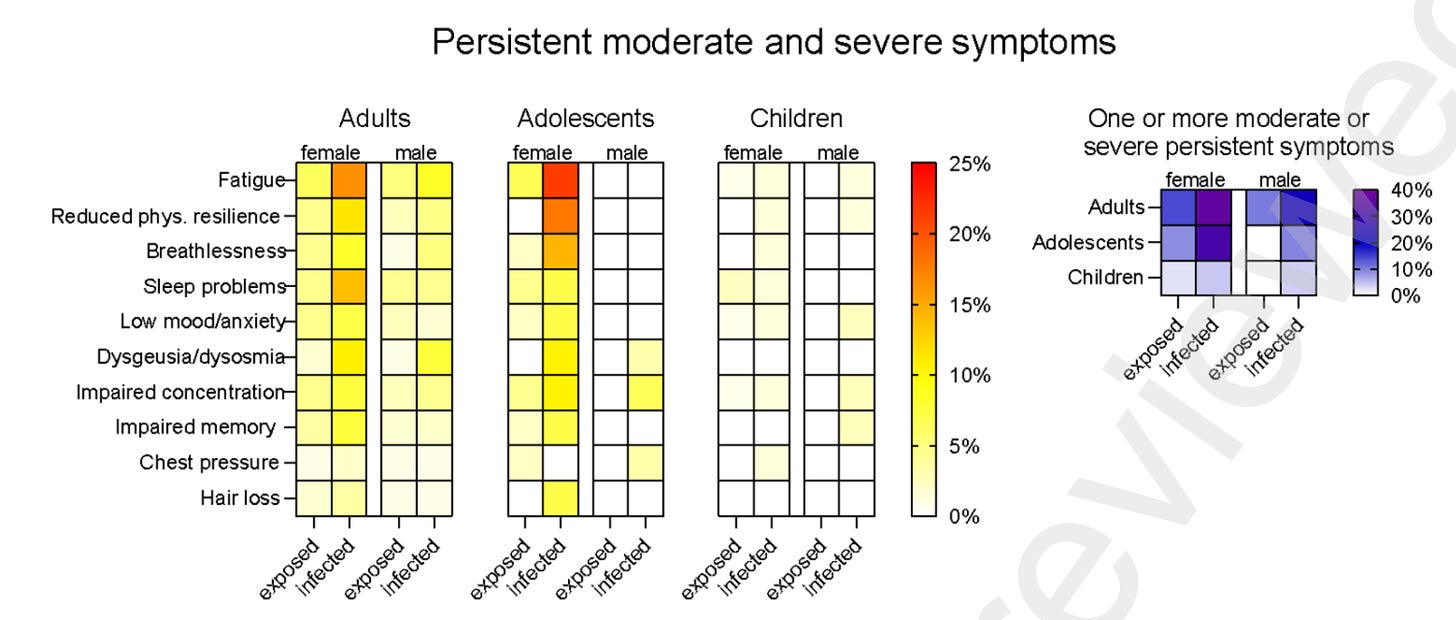

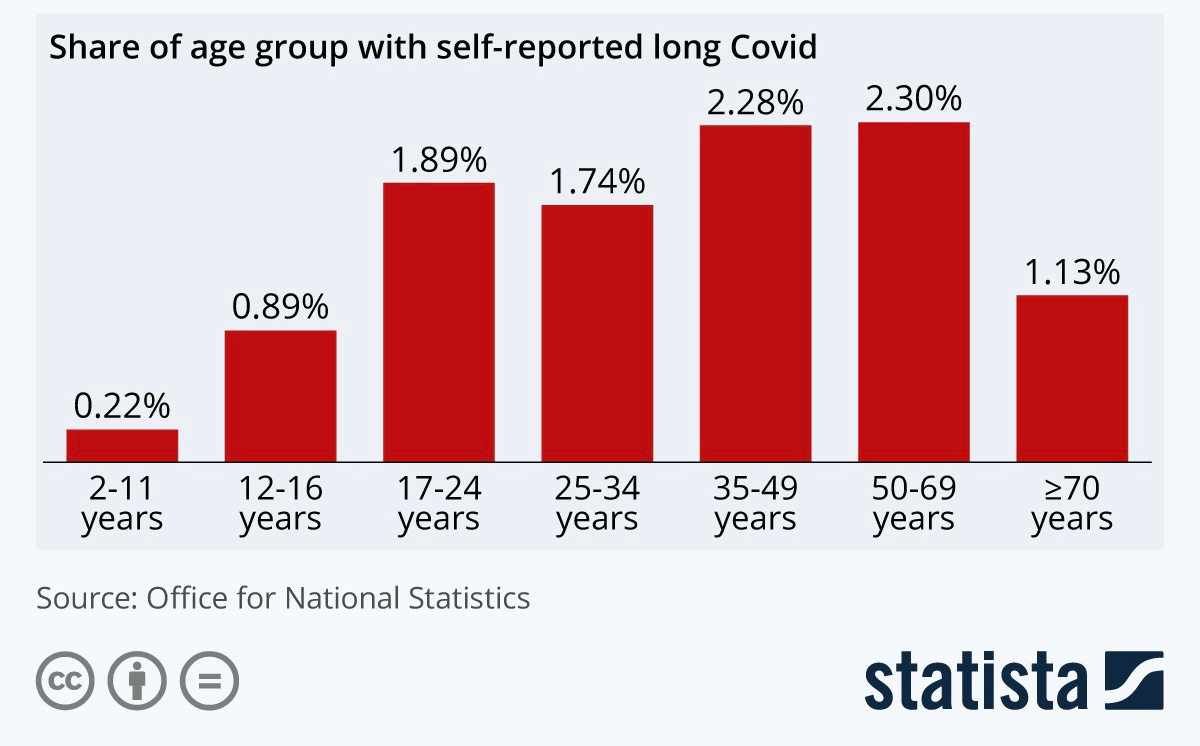

Regardless of the exact burden, there is a very strong consensus that long COVID is significantly lower among children compared to adults. The comparative risk is nicely displayed in the figure below, which used data from the U.K. We hypothesize long COVID is less common among children because they have fewer SARS-CoV-2 doors (i.e., ACE2 receptors) on their organs. So they are less likely to get infected and less likely to have severe disease. Thus, less likely to have long COVID.

Symptoms

The symptom profile of long COVID is subtly different among children compared to adults. This is because acute disease tends to develop differently in children. While adults have many more acute respiratory problems, children tend to have more acute digestive problems. A very recent study found children with severe long COVID tended to have a leaky gut biomarker in their blood. This is a digestive condition which allows gut microorganisms to seep into the bloodstream, which would result in different symptomology than what adults experience.

Nonetheless, symptoms can still vastly range. A recent meta-analysis found fatigue was most commonly reported 12 weeks after infection among children, followed by headaches, abdominal pain, muscle pain, and concentration issues.

Dr. Ian Ferguson, a clinician who treats kids at the Yale long COVID clinic, characterized symptoms nicely:

“What I tend to see is a generalized achiness and a decrease in physical conditioning. They might say, ‘I just feel achy. I don’t feel right.' An otherwise healthy child may say, ‘I don't feel like I should get out of bed in the morning.’ Or they say, ‘I used to be on the high school cross country team. And now I can barely make it down the street before I have to take a break.’”

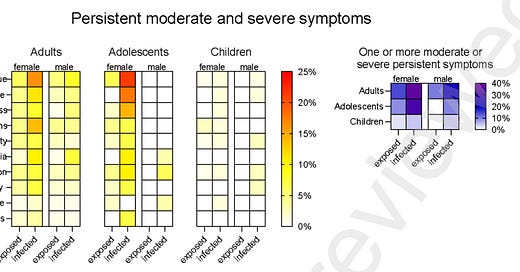

Interestingly, severity of symptoms seems to be strikingly different by gender and age of children. A recent study found that while male adolescents and young children didn’t report long COVID 12-months after infection, 54% of adolescent girls (aged 14-18) reported long COVID. Of which, 1/3 were classified as moderate or severe. The most severe symptom was fatigue followed by reduced physical activity and breathlessness, as displayed in the figure below.

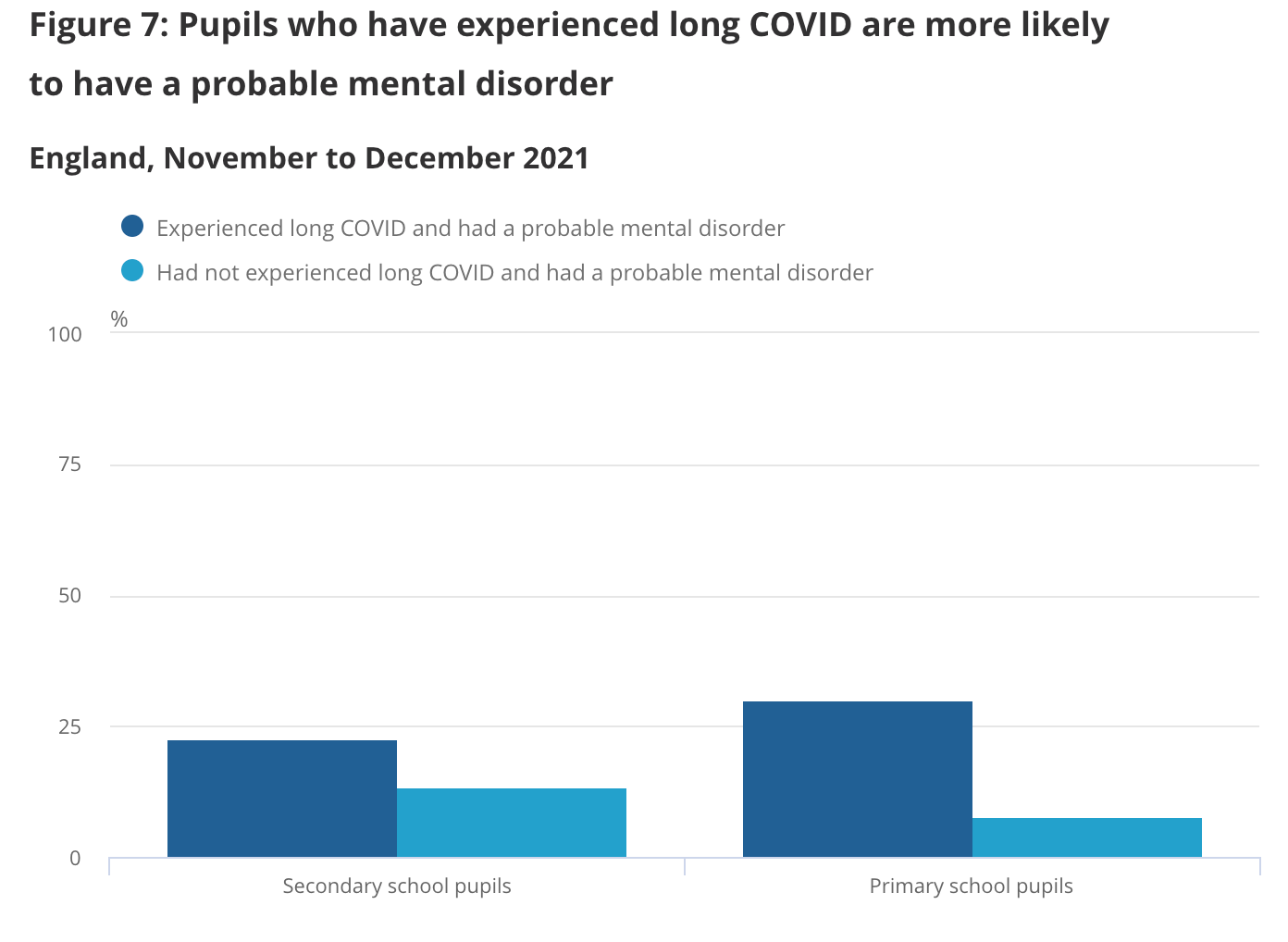

The U.K. found a slightly different signal in their latest official report on long COVID. Primary-aged children with long COVID had a higher risk of mental disorders compared to children without long COVID. They found no relationship between long COVID and mental disorders among secondary-aged school children.

Unfortunately, among children who do have long COVID, symptoms can be debilitating. One study found those with long COVID reported 16 or more sick days compared to children without long COVID (18.2% compared to 11.6%) and 16 or more days of school absence (10.5% vs 8.2%).

How long do symptoms last?

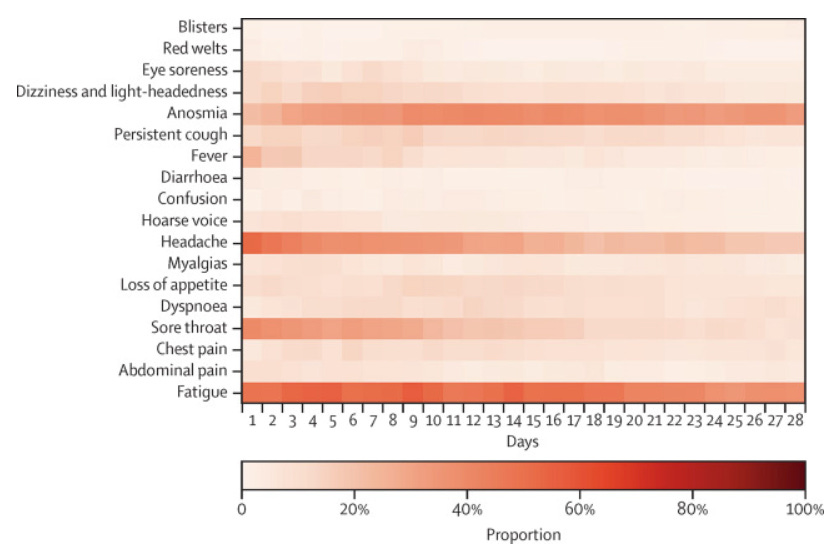

Thankfully, the majority of symptoms are short lived. Within the first 28 days, symptoms significantly recede over time (see figure below). By day 56, 98.2% of children recovered from all symptoms.

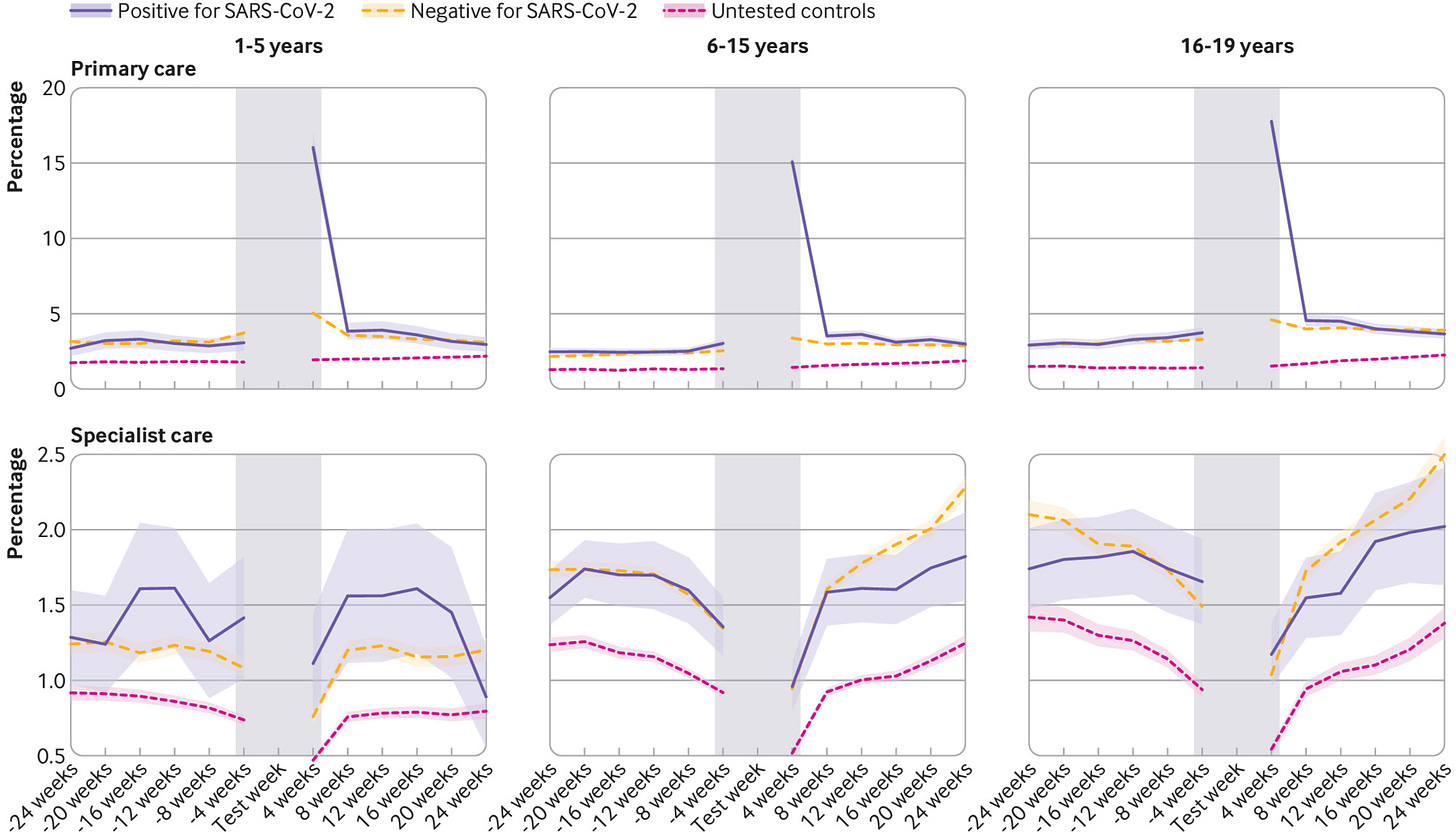

A group in Norway used a nationwide database to assess the impact of COVID19 on long-term healthcare usage among 700,000 children and adolescents. This is an innovative approach because it doesn’t rely on self-report. They found that healthcare usage increased within the first 4 weeks after a COVID19 infection. However, after 12 weeks, healthcare usage (primary care and specialty care) was not increased for 6-19 year olds. There was a slight increase (13%) in primary care usage for 1-5 years from 13 to ~24 weeks after infection compared with participants of the same age who tested negative. This suggested preschool-aged children may take longer to recover.

Long COVID among family members

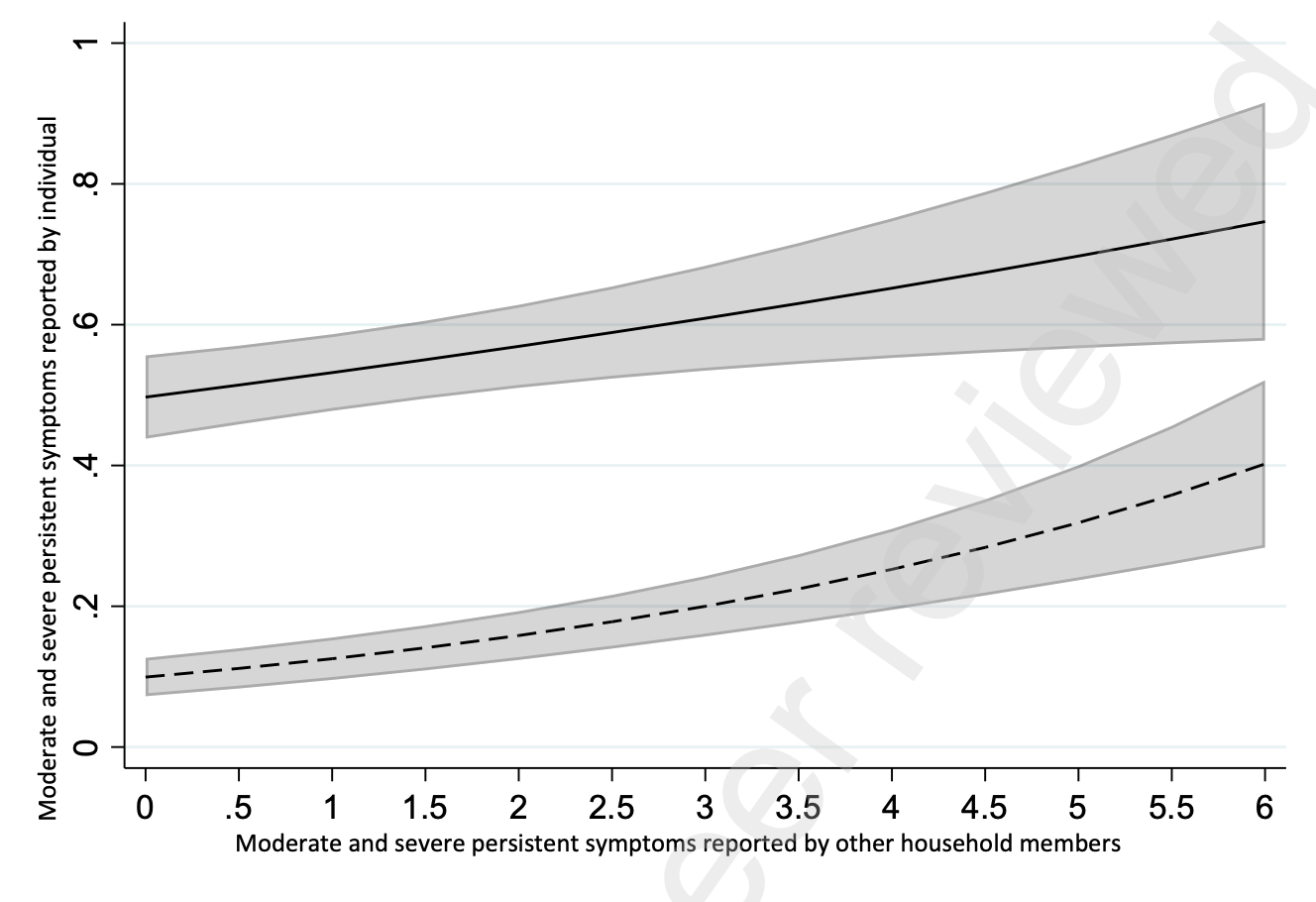

One of the more interesting scientific findings is about the impact of family on long COVID. German scientists studied 341 households each with at least one confirmed infection between May-August 2020 (call this Time 1). The scientific team then contacted the households 11-12 months later (call this Time 2) to assess long COVID. What did they find?

Among households in which the parents reported severe symptoms during infection (Time 1), the children were more likely to report long COVID 12 months later (Time 2).

The number of moderate/severe long COVID symptoms experienced by one person in the household was related to the number of long COVID symptoms experienced by other people in the household (see figure below).

As the authors point out, this relationship could be due to a number of things. For example, shared genetics could pre-dispose parents and children to severe disease and long COVID. It could also be due to behavior. For example, parents who experience severe disease may be more aware of pediatric symptoms related to COVID. Parental behavior, like stress, has also been shown to significantly influence child symptoms in a range of other health conditions.

Impact on chronic conditions

Long COVID studies have largely focused on symptoms, like headache and fatigue, that may signal underlying damage from the virus. But it’s important to recognize the potential impact a virus has on chronic conditions beyond 12 months.

Since the 1950s, viruses have been directly linked to a number of chronic conditions. It’s known, for example, that infant RSV infection increases the chances of asthma by 30-40% in the first decade of life. Among severe influenza infections, about 4% of children have neurological problems, like seizures. Enteroviruses, like rotavirus and mumps, have also been shown to trigger type I diabetes among children. Chronic fatigue syndrome can be caused by viral infection and autoimmune dysregulation and is present in 0.65% of children.

So, to epidemiologists, it wasn’t too surprising to see a January 2022 MMWR publication that linked SARS-CoV-2 infection to new diagnoses of diabetes among children in the U.S. While there were a number of limitations to this study, the biological plausibility is certainly there. We need to continue to investigate these signals. And who knows? Maybe investigation into SARS-CoV-2 can also provide answers about other post-viral syndromes in children.

Bottom line

Thankfully long COVID among children is very rare. But a very small number can become big when a virus burns through entire populations. We need more rigorous studies (with comparison groups and attempts to remove potential biases), so we can pinpoint true incidence, understand biological pathways, and comprehend the long-term implications for children, like treatment options. Right now, we have a lot of questions with very few consistent answers.

Love, YLE

“Your Local Epidemiologist (YLE)” is written by Dr. Katelyn Jetelina, MPH PhD—an epidemiologist, biostatistician, professor, researcher, wife, and mom of two little girls. During the day she has a research lab and teaches graduate-level courses, but at night she writes this newsletter. Her main goal is to “translate” the ever-evolving public health science so that people will be well equipped to make evidence-based decisions. This newsletter is free thanks to the generous support of fellow YLE community members. To support the effort, please subscribe here:

Well written

Apologies for the off-topic comment. Perhaps a topic for the future. I'm seeing numbers in Europe going back up again, even though they're still very high from Omicron. I can't find any coverage. Is it a new BA.2 wave reinfecting the previously infected? Some new variant? Here in the US our numbers have come way down, so we're relaxing, although home testing may be obscuring the true covid rate. But Europe is looking scary!