This week I’m diving deep into long COVID. This mini-series is 5 posts in total: burden, impact on specific organs, predictors, kids, and potential treatment. This is post #2 of the series.

Long COVID patients have reported more than 200 symptoms across 10 organ systems. While all symptoms can be serious and are important to investigate, the impact on vital organs, like the heart, are of most concern. The heart doesn’t easily mend after damage, and the long-term implications can be dire.

How does SARS-CoV-2 impact the heart?

Unfortunately, just like with long COVID in general, we don’t know the exact mechanisms through which SARS-CoV-2 impacts the heart. But four pathways continue to be explored:

The heart has ACE2 receptors (i.e. doors for the virus to enter), so the virus has the potential to cause direct damage to the heart cells;

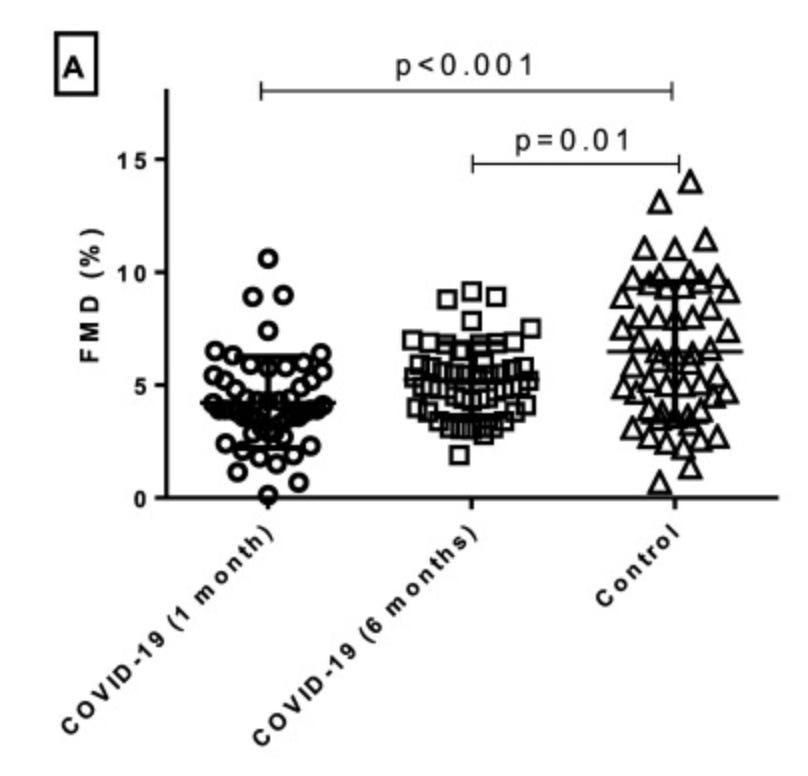

Infection impacts the inner surfaces of veins and arteries, which seems to do a lot of damage. For example, a recent study found that 6 months after infection arteries were less able to widen thus restricting blood flow.

Intermediate and long-term effect of COVID-19 on endothelial function. A) Follow-up evaluation of endothelial function at 1 and 6 months after hospitalization for COVID-19 demonstrated significantly impaired flow-mediated dilation (FMD) when compared to propensity score-matched controls. Damage to arteries and veins can also cause inflammation in blood vessels and cause very small blood clots to circulate in the blood stream. Together, all of these can compromise blood flow and, thus, damage the heart. For example, we’ve seen too much inflammation impacts the electrical signals to beat properly, which causes heart pumping problems or abnormal rhythms;

Lung damage prevents oxygen from reaching the heart muscle, which in turn damages the heart. This makes it so the heart has to work harder to pump blood; and/or,

Indirect damage from the nervous system. A condition called POTS (postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome) may be linked to COVID. This is when the neurons that regulate heart rate and blood flow are damaged and thus cause cardiac symptoms.

Long-term (12 month) impact

Last month, a group of scientists made a splash with an incredibly strong study published in Nature. Scientists used a large, powerful database from the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) to evaluate 153,760 people with a COVID-19 infection between March 1 2020 and January 15, 2021 (called “cases”). Among these cases, 131,000 patients were not hospitalized for COVID19, 16,700 were hospitalized, and 5,800 were admitted to the ICU. The scientists extracted data from medical records to assess 20 heart health outcomes, like stroke, heart attacks, or arrhythmias, 12 months after their SARS-CoV-2 infection.

Then, they compared “cases” (i.e., had an infection) to “controls” (i.e., didn’t have an infection). There were two different control groups:

5,637,647 people with no confirmed infection. Scientists looked at their heart heath during the same period as the cases; and,

5,859,411 people with medical records including heart health during 2017 (i.e., before the pandemic, called historic controls). This second comparison group is critical because it removes doubt that some of the controls may have been asymptomatic or never tested.

What did they find?

Those with a history of COVID19 infection were more likely to have the following 12 months later: strokes, dysrhythmias (five different kinds), inflammatory heart disease (like myocarditis), heart disease (four different types, including heart attacks), other cardiac disorders (like heart failure), and clotting issues (like pulmonary embolisms).

The risks for each of these varied. For example, the risk of a heart attack was 63% higher among those with a prior COVID19 infection compared to those without an infection. The risk for myocarditis (inflammation of the heart) was 538% higher.

Heart outcomes were elevated among the infected regardless of age, race, sex, obesity, smoking, high blood pressure, diabetes, high cholesterol, or having a pre-existing heart problem.

For those not hospitalized, risk of 17 heart outcomes over 12 months was higher among those with a COVID19 infection, compared to those without infection. But risk was far higher among hospitalized patients versus those who were not hospitalized.

For example, the risk for stroke among non-hospitalized cases was 23% higher compared to controls, but the risk of stroke among ICU patients was 435% higher than controls.

One of the strongest aspects of this study was that the scientists also provided absolute risks or excess burden. Absolute numbers are critical in public health, because they provide context. For example, when we say a “50% increase risk for stroke” this could mean an increase from 10,000 to 15,000 people or from 4 to 6 people. While neither are great, the public health implications of the two are very different.

This study provided excess burden for each one of the 20 heart outcomes (see the right-hand column in the figure above) by severity of SARS-CoV-2 disease (hospitalization or not). For example, with stroke:

Non-hospitalized: The absolute risk for stroke was 9.79 per 1000 among those with a prior infection. This is compared to 7.94 per 1000 among those without an infection. So excess burden was 1.85 strokes due to COVID19 among non-hospitalized.

ICU: The absolute risk for stroke was 34.06 per 1000 among those with a prior infection compared to 7.94 per 1000 without a prior infection. This equates to excess burden of 26.12 strokes.

A similar pattern was shown for the other heart outcomes, too. While risk is higher among non-hospitalized patients, it’s still very rare. Negative heart outcomes are far more common among those hospitalized for severe disease.

Impact of vaccination

It’s important to note that this study included people who were infected with SARS-CoV-2 between March 1, 2020 and January 15, 2021. This means vaccines were not readily available for the general public at time of infection. Thankfully, we’ve seen a number of scientific studies show vaccination reduces long COVID19 by 40-50%. We haven’t seen the evidence for the positive role of vaccines on long COVID heart health specifically. But given that vaccines reduce the likelihood of infection and hospitalization, I’m optimistic that negative heart outcomes are significantly reduced, too.

Bottom line

Although relatively rare, SARS-CoV-2’s long-term impact on the heart can be detrimental even among previously healthy individuals and among those with mild COVID19 disease. Vaccination continues to be our best bet to reduce the chances of disease, like the impact on the heart.

Tomorrow’s post will be on the burden of long COVID on kids. Stay tuned!

Love, YLE

P.S. There was a lot of news yesterday about a published study on long COVID and the brain. The preprint was released last summer and my summary can be found here.

“Your Local Epidemiologist (YLE)” is written by Dr. Katelyn Jetelina, MPH PhD—an epidemiologist, biostatistician, professor, researcher, wife, and mom of two little girls. During the day she has a research lab and teaches graduate-level courses, but at night she writes this newsletter. Her main goal is to “translate” the ever-evolving public health science so that people will be well equipped to make evidence-based decisions. This newsletter is free thanks to the generous support of fellow YLE community members. To support the effort, please subscribe here:

The micromorts you discussed in your "Understanding Risk" post really helped me get perspective on the risks of getting COVID, to the point where I was considering giving up my "extreme social distancing," but I wanted to hear what you had to say about long COVID first. Now, I'm worried that we're in it for the long haul... but if micromorts for these long COVID heart and brain risks were available (knowing that they would only be based on the minimal info we have so far, which is better than nothing), perhaps it would help put my fears in check, even if only ever so slightly. Last but definitely not least, THANK YOU SO MUCH from the bottom of my heart for helping us all make truly informed decisions, not decisions based on sound bites in the news, which often seems only marginally better than the info on social media.

A comment not about this article: I would appreciate hearing your take on the latest variant BA.2. Seeing contradictory things on Twitter from the virologists, etc.