Malaria in the states: A sign of climate change?

Yes and no. It’s a little complicated. Here’s why.

In the past two months, five cases of malaria were reported in the U.S.: four in Florida and one in Texas. This prompted the CDC to disseminate a Health Alert Network (HAN) advisory last week—a warning to physicians to stay alert for cases.

Each year, about 2,000 cases are reported, so malaria isn't new in the U.S., albeit rare. However, this is the first time in 20 years that these cases were not linked to travel. This means five people were infected from mosquitoes flying around the states.

For now, the risk to the public is very low. However, many are naturally asking: Is this due to climate change?

Yes and no. It’s a little complicated. Here’s why.

Malaria is an old problem for the United States

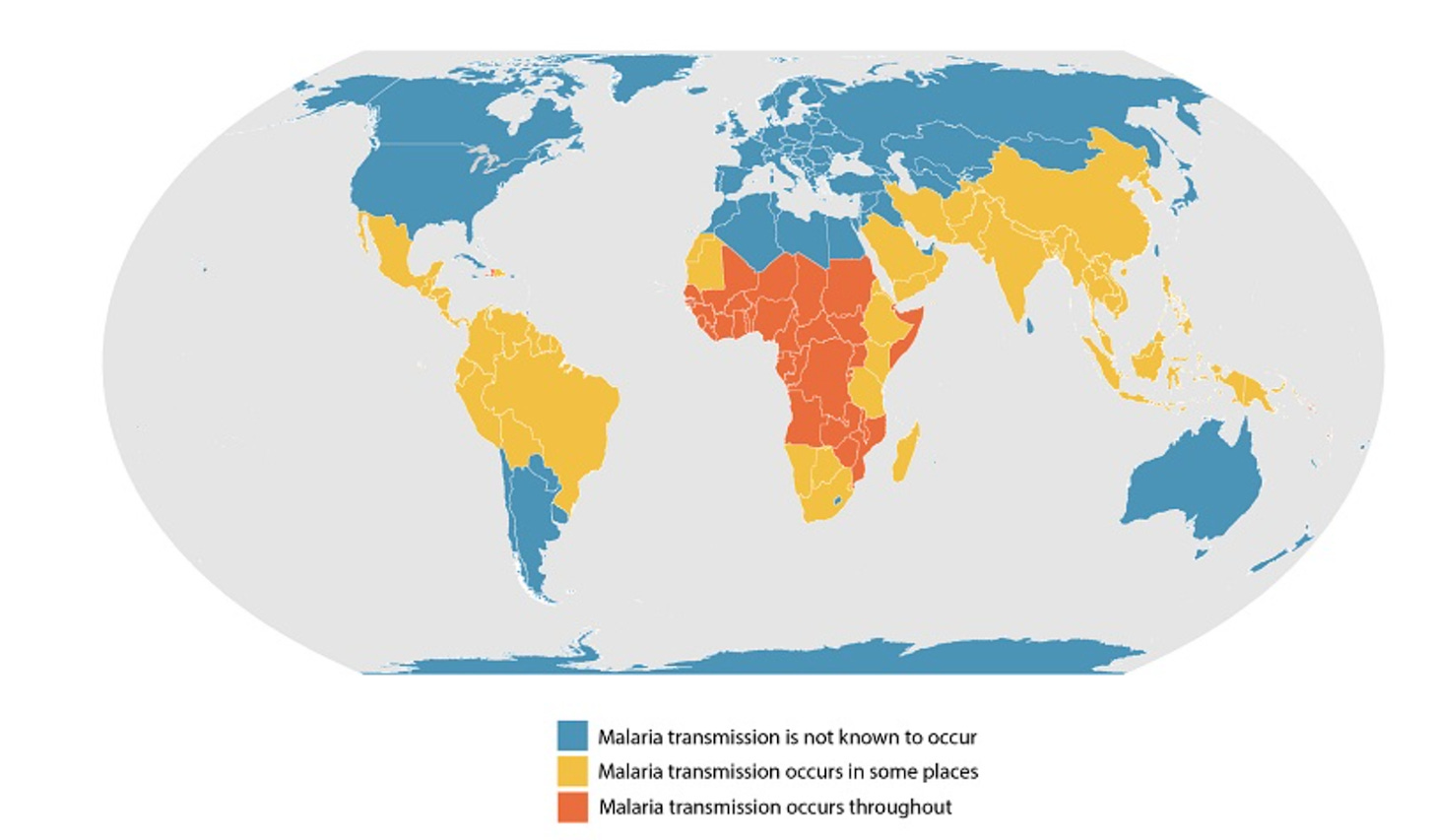

Malaria is a huge global health challenge. In fact, half the world’s population—especially in poorer, hotter countries—are impacted by malaria. It’s one leading cause of death in developing countries.

Malaria needs three things in order to be endemic:

The right vector. There are many different types of mosquitoes. Malaria-transmitting mosquitoes are found on every continent, including the U.S.

The right temperature. Mosquitoes are cold-blooded, so malaria transmission is a bit like a chemistry experiment. If it’s too cold (below ~16°C, or ~60°F), the mosquito life cycle slows down too much to spread disease. Closer to the “magic temperature” of ~25°C (77°F), mosquitoes are happier—and parasites spread a little bit easier from mosquito to human.

The parasite needs to be present. Malaria is not a virus, but rather a parasite. Mosquitos spread this parasite by sucking the blood of an infected person.

Before 1949, the U.S. had all three of these, particularly in the South. That means malaria was endemic in the states. But the parasite was eliminated by spraying a ton of insecticides. (Think Silent Spring!) In other words we eliminated #3 in the equation above, while the other two factors stick around.

Today, recent non-travel related cases means: the right type of mosquito found an infected traveler, is now carrying the malaria parasite and infecting others, and went undetected for a bit too long. Epidemiologists are moving fast to ensure malaria remains eradicated in the U.S. We’re optimistic about success.

Will things change because of climate change?

Climate change brings warmer weather, which equals more mosquitoes. Warmer weather means two things:

Migration. Malaria mosquitos are moving, but it doesn’t really matter to the U.S., because they are already here. Other types of mosquitoes that aren’t native to the U.S. are also moving because of climate change. In the last few years, other mosquito-borne diseases (think dengue fever, or Zika virus) have started to show up in the U.S. and Europe.

Transmission. It’s easier for mosquitoes to transmit diseases because of more ideal temperatures.

Public health implications

Are we about to have a massive malaria outbreak? Very unlikely. Teams in Florida and Texas are already spraying insecticides in the areas where cases were reported. This isn’t our first rodeo. If you are in those specific areas, here’s what you’re supposed to do. Outside of those neighborhoods, the risk to the public today is very, very low.

Will we be dealing with more malaria outbreaks in the next 10-20 years? Maybe. This essentially depends on if our public health systems can keep up. There are two key factors:

If endemic regions don’t address increased malaria transmission, we may get more sick travelers (and miss more cases).

A new invasive malaria mosquito (Anopheles stephensi) has started to spread out of southern Asia into the rest of the world. And, just like the mosquitoes that spread dengue and Zika, this malaria mosquito loves our landscapes—cities, standing water, and hot weather. It could easily come to the U.S.

Does wastewater pick up malaria? It has the capability to, but we need the right tests in place. Right now we know it’s possible in the lab, but has yet to be implemented in the real world. Teams are actively trying to validate an assay in Florida.

Bottom line

Malaria could have a comeback in the U.S.; it’s plausible in the absence of climate change, but more probable with climate change. In the meantime, the U.S. is already facing at least a dozen other mosquito-borne diseases that are made much worse by climate change—and other countries will need extra support if they’re going to eradicate malaria like we did.

It’s essential that our public health systems keep up. Probably a bad time to be defunding public health yet again.

Love, YLE and CC

Dr. Colin Carlson is a climate epidemiologist at Georgetown University in Washington, D.C. You can see what his lab is working on at carlsonlab.bio, or look for him on Capital Crescent bike trail most afternoons.

“Your Local Epidemiologist (YLE)” is written by Dr. Katelyn Jetelina, MPH PhD—an epidemiologist, wife, and mom of two little girls. During the day she is a senior scientific consultant to a number of organizations. At night she writes this newsletter. Her main goal is to “translate” the ever-evolving public health world so that people will be well equipped to make evidence-based decisions. This newsletter is free thanks to the generous support of fellow YLE community members. To support this effort, subscribe below:

See https://ajph.aphapublications.org/doi/abs/10.2105/AJPH.40.11.1405 for a contemporaneous 1950 description of how autochthonous malaria was eliminated in the continental US. A key ingredient was development and implementation of a surveillance case definition, with case report forms forwarded to a central authority (at CDC) for review against the case definition. This allowed public health workers to ignore a very large fraction of the case reports, which had a low probability of actually being malaria, and to focus their efforts where there actually was continuing transmission.

Also, don't underplay the importance of increases in the prevalence of air conditioning and of effective screens in reducing the transmission of mosquito-borne illnesses. During my time in Florida public health (1990-2012) we saw a recurring pattern that transmission of such illnesses (Saint Louis Encephalitis, West Nile Virus, Zika, etc as well as malaria) happened among people who spent time in the evening sitting outside their modest homes to get cool, because of no or limited air conditioning. Sleeping outside because of lack of housing is also an obvious risk factor. So you need not just the right vector etc but also opportunities for people to be exposed to infected mosquitoes.

Thank you. As a gardener it is also a timely reminder to check for standing water.