Our Youth are Struggling with Mental Health

… and COVID-19 is making it worse.

Si quiere leer la versión en español, pulse aquí.

This post contains sensitive information including discussion of suicide. If you are in need of help, there are an abundance of resources on the National Suicide Prevention Hotline website. They also have an anonymous chat function, or you can call 800-273-8255.

On October 19, 2021, the American Academy of Pediatrics, the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, and the Children’s Hospital Association issued a declaration that children’s mental health had become a “national emergency.” The U.S. Surgeon General followed on December 7 with his own 53-page advisory on the dire state of youth mental health. Mental health challenges are rising among kids, which seems to be due to a perfect storm of increasing mental health challenges before the pandemic and a highly disruptive pandemic.

Mental health challenges, as defined by the U.S. Surgeon General on page 6, are: “symptoms that cause serious difficulties with daily functioning and affect our relationships with others, as in the case of conditions such as anxiety disorders, major depressive disorder, schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, and eating disorders, among others.”

Before the pandemic

Mental health challenges among children and youth are not new. Before COVID-19, pediatric mental health disorders were high: up to 20% of children and youth experience a mental health disorder in any given year, and the percentage has been increasing in recent years. The rate of suicides among 10-24 year-olds steadily rose between 2010 and 2018, and suicide was the second leading cause of death for the 10-24 year old age group in 2018.

Immediately following stay-at-home orders

Then COVID-19 hit. In-person school was closed, and children lost out on school-related activities and milestones. The isolation of remaining at home, concerns about the future, and potential economic strains on families contributed to declines in mental health. It’s clear from multiple studies that the first month or two of the pandemic significantly impacted mental health of kids.

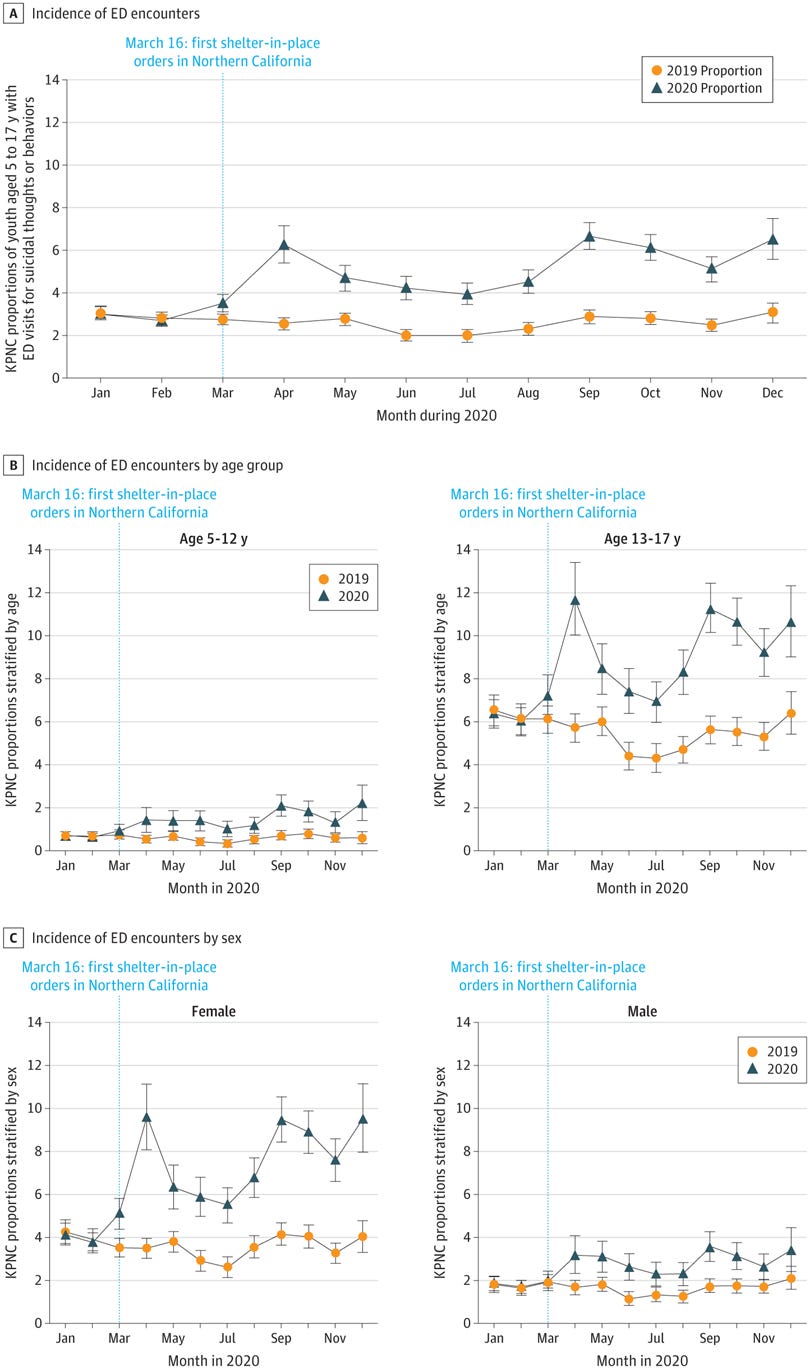

At the beginning of the pandemic (April 2020), the proportion of pediatric emergency department visits for all mental health-related reasons increased 24-31% (depending on age). Then it stayed high for the rest of the year.

Specifically, research found the number of youth going to the ED for suicidal thoughts and behaviors increased from the start of the pandemic and remained higher than 2019. Overall, risk of presenting with suicide-related concerns was 133.5% higher among youth aged 5 to 12 years and 69.4% higher among youth aged 13 to 17 years, compared to 2019. Rates increased throughout the year for girls, specifically.

Later in the pandemic

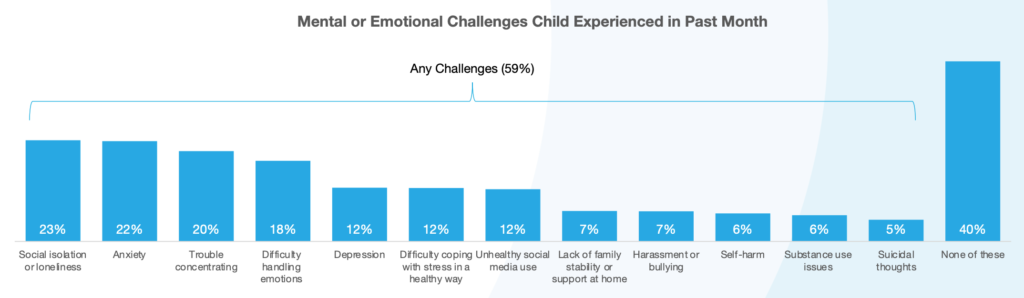

At the end of 2020, a national survey was conducted by the Jed Foundation to assess youth well-being during the pandemic. They found that 1 in 3 families reported their child’s emotional health was worse than before the onset of COVID-19. The most common challenges that children experienced were loneliness (23%) and anxiety (22%), followed by trouble concentrating (20%).

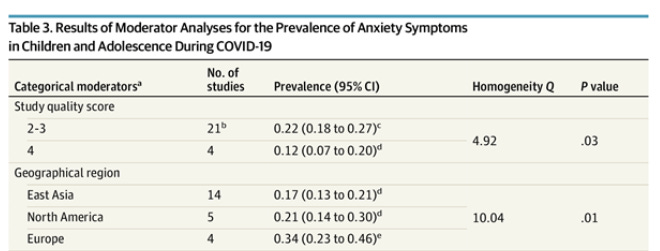

Then, in August 2021, JAMA pediatrics published an article that reviewed 29 studies with over 80,000 youth worldwide. They found that 25.2% of youth experienced depression, and 20.5% experienced anxiety during the pandemic worldwide, which is double that of pre-pandemic estimates (11.6% for depression pre-pandemic and 12.9% for anxiety pre-pandemic). Interestingly, the rates of depression and anxiety were higher later in the pandemic, particularly among older adolescents and girls. Also, interestingly, the rates of anxiety were highest among adolescents in Europe (34%) and North America (21%).

Most recently (August-September 2021), NPR, the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, and Harvard polled parents to assess the impact of the Delta wave on children. They found that 36% of households with children struggled with stress, anxiety, depression, or sleeping difficulties. Additionally, over a third of families reported severe challenges in social support (like child care).

The interest in mental health has never been greater. According to Google’s Year in Search, “how to maintain mental health” was searched more globally in 2021 than ever before. The figure below shows the popularity of mental health Google searches over time. The Y-axis shows the relative popularity of that search. So, 100 reflects the peak of popularity in 2021. A 50, for example, shows that the search term was half as popular at that time.

What’s the country’s plan to address this?

The Department of Education unveiled new guidance for supporting child mental health needs. In August, the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services pledged $85 million in funding to expand mental health services for children and youth. The “national emergency” declaration and the Department of Education's new resource included many key calls to action:

Reduce stigma. A CBS poll from 2019 showed that nearly 90% of individuals think stigma is associated with mental illness. Children with mental health conditions who experience stigma are often marginalized and forced out of classrooms or groups, which can result in low self-esteem and secrecy. The barrier of stigma exists even if sufficient services are available for children and youth.

Address current funding gaps. The entire mental health field for children and youth has been historically underfunded. Funding is necessary to provide evidence-based mental health screening, diagnosis, and treatment to all children and youth and address the current bed and resource shortages. Funding is also needed to expand the children’s mental health workforce and improve the mental health knowledge of educators. School districts also need funding to collect and access data that can inform mental health-related decisions for communities.

Coordinate services. The current delivery systems for mental health care are fragmented, and many children and youth are not receiving comprehensive services. Many services are offered at separate facilities with different providers and different funding streams. Mental health care should be integrated into primary care pediatrics, and community-based systems should connect families with resources. Telemedicine services should also remain available even when hospitals and clinics reopen to the public.

Advance health equity. Many groups (including LGBTQ+, youth of color, and youth from low-income families) are disproportionately impacted by mental health. Organizations must prioritize equity when expanding and implementing services.

What can parents do?

Authors in the Journal of Pediatric Health Care offered recommendations for addressing youth mental health challenges. What can parents do?

Daily routine. Work to keep children’s routines as “normal” as possible and engage in practices that improve the overall health of children and youth. Eat healthy meals together as a family, help them have a consistent sleep schedule, and make sure they are regularly attending school whether in-person or remote.

Validate your kids’ experiences. Talk honestly with them, and let them know that their emotions are real and ok to feel. Let them know that you love them and that you will get through this difficult time together.

Seek help. Just as routine screenings occur for physical health, screenings should also be done for mental health. Talk with your pediatrician or family doctor if you have any concerns or need help finding a mental health professional. School counselors can also be a helpful resource.

Safety. Keep medications – especially ones that are dangerous in overdose – and firearms locked up so that there is no chance that your children or their friends could access them.

Bottom line: Children had (and continue to have) a rough time during this pandemic. There’s a lot we can do on a national level, but also on an individual level to prioritize the needs of kids during this tough time.

Love, YLE, Rebecca Molsberry, and Dr. Lisa Uebelacker

Ms. Molsberry is my rockstar PhD candidate with expertise in mental health epidemiology. Because she doesn’t have enough to do (!) she graciously offered to keep the YLE community updated on mental health research across the world – a topic the YLE community has voiced considerable interest in.

Dr. Lisa Uebelacker is a Professor in the Department of Psychiatry and Human Behavior at Brown University and Co-Director of Behavioral Medicine and Addictions Research at Butler Hospital in Providence Rhode Island.

Other recent scientific highlights in mental health:

Ongoing Disparities in Digital and In-Person Access to Child Psychiatric Services in the United States - J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. This study estimated that 6,035,402 children in the U.S. (approximately 10%) have inadequate availability of child psychiatric services within their counties. This is espeically true among kids rural or low-income counties.

Mental health concerns during the COVID-19 pandemic as revealed by helpline calls - Nature. A study investigated 8 million helpline calls in 19 countries and found that call volumes peaked at 35% above pre-COVID-19 levels during the first wave of the COVID-19 crisis. Fears about the pandemic and loneliness drove the increases in calls rather than suicidal ideation, relationship issues, or economic concerns.

Trends in U.S. patients receiving care for eating disorders and other common behavioral health conditions before and during the COVID-19 pandemic - JAMA Network Open. Starting in June 2020, the rate of hospitalizations for eating disorders doubled and remained elevated throughout the remainder of 2020.

FCC approves text-to-988 access to suicide prevention lifeline- FCC. On November 18, 2021, the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) voted unanimously to expand access to the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline by allowing individuals to send text messages to reach the Lifeline directly.

I feel this in my bones, Dr. J.

I am a single mom to an 8yr old (asthmatic and immune-compromised) and a 6yr old. We haven’t had traditional in-person school since April 2020. My older daughter had a HALF a year of “normal” Kindergarten. But I cannot send my kids to school even now (with them vaxxed) because my state (Georgia) has no mitigations in schools and very low vaxx rate and just yesterday, the Governor lifted any remaining requirements for schools to contact trace/isolate/quarantine. The risk to my immune-compromised child is too great to send her to school.

So, here we are, 21 months into this, with no light at the end of the tunnel and a state that has decided to let Covid rip. My kids are starting to really show the strain of uncertainty and isolation. They miss other kids so much… but other kids (overwhelmingly unvaxxed here) are the biggest risk to my child’s health. I am starting to get really scared because I see their mental health starting to decline, but I live in a community that has decided not to value the vulnerable. My choices in this situation as a parent are all bad, terrible, and risky.

And for me? As a parent? Let’s just say that I am in weekly therapy and antidepressants and just trying desperately to cope with an utter lack of normalcy, no federal or state leadership to manage public health during this pandemic, no social structure (no family nearby and having to keep physical distance from friends because of risk), and a progressively less flexible and understanding workplace.

Thank you for speaking to this. I feel increasingly overwhelmed, terrified, squeezed, and rudderless. I am not sure how much longer many of us can hang on.

This post is important and excellent. Nonetheless it is crucial for epidemiologists, especially, to recognize a severe defect in youth suicide reporting. For generations epidemiological and clinical understanding of mental illness has been constrained by the symptom complexes defined in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of the American Psychiatric Association (DSM). The DSM-5 attends to child maltreatment trauma only at the end of the volume after defining the accepted diagnostic categories for various mental illnesses based on symptom complexes. On page 715, there is a brief section called “Other Conditions That May Be as Focus of Clinical Attention.” Here it states that the conditions listed there merely affect mental disorders; they are not mental disorders themselves; and they cannot be treated as mental disorders. Thus designated by the DSM-5 coding system, they are not reimbursable by insurance companies. Conditions relegated to this section include Child Physical Abuse, Child Sexual Abuse, Parent-Child Relational Problems, Child Affected by Parental Relationship Distress, Child Psychological Abuse, Spousal Violence, and others. Although the ICD-10 recognizes these categories, the USA depends on the outdated DSM system, thus the presence of any of these conditions is rarely specifically coded in an American child’s clinical medical record. Thus American records cannot be validly curated into ICD-10 form. This presents a major problem to clinicians who study and treat the effects of child abuse trauma and associated morbidities, not to mention suicide prevention efforts.

For instance, in most pre-covid, baseline studies of youth suicide, the presence or absence of child maltreatment trauma is simply not mentioned. Child maltreatment trauma is not mentioned as a diagnosis or comorbidity in the 2021 JAMA meta-analysis of youth suicides cited here. It is commonly thought that the pressure cooker family environment created by covid-19 markedly increased the incidence and prevalence of child maltreatment, but there is some confusion due to a decline in reporting resources at the same time. It is important to know how much of the observed increase in youth suicides is associated with child maltreatment trauma and potentially its differential impact in specific youth sub-populations. But there is no data! We do not know because of the outdated and inadequate coding system promulgated by the American Psychiatric Association.