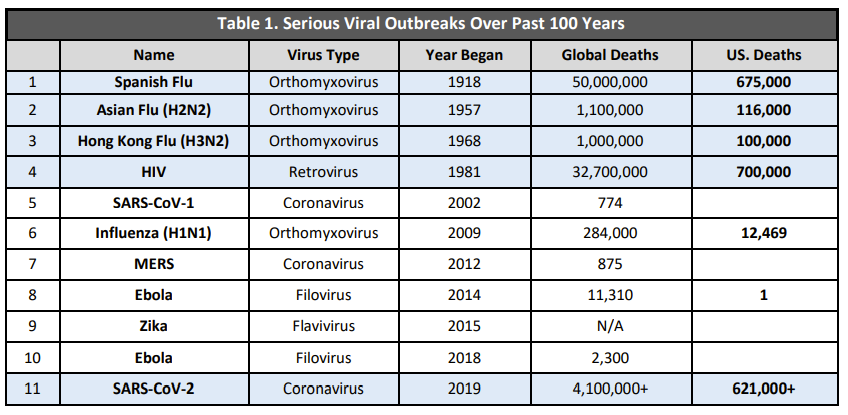

The U.S. is at a pivotal moment. We can learn from our mistakes to prepare for future mutations and new public health threats. Or we can continue a “deadly cycle of panic and neglect”.

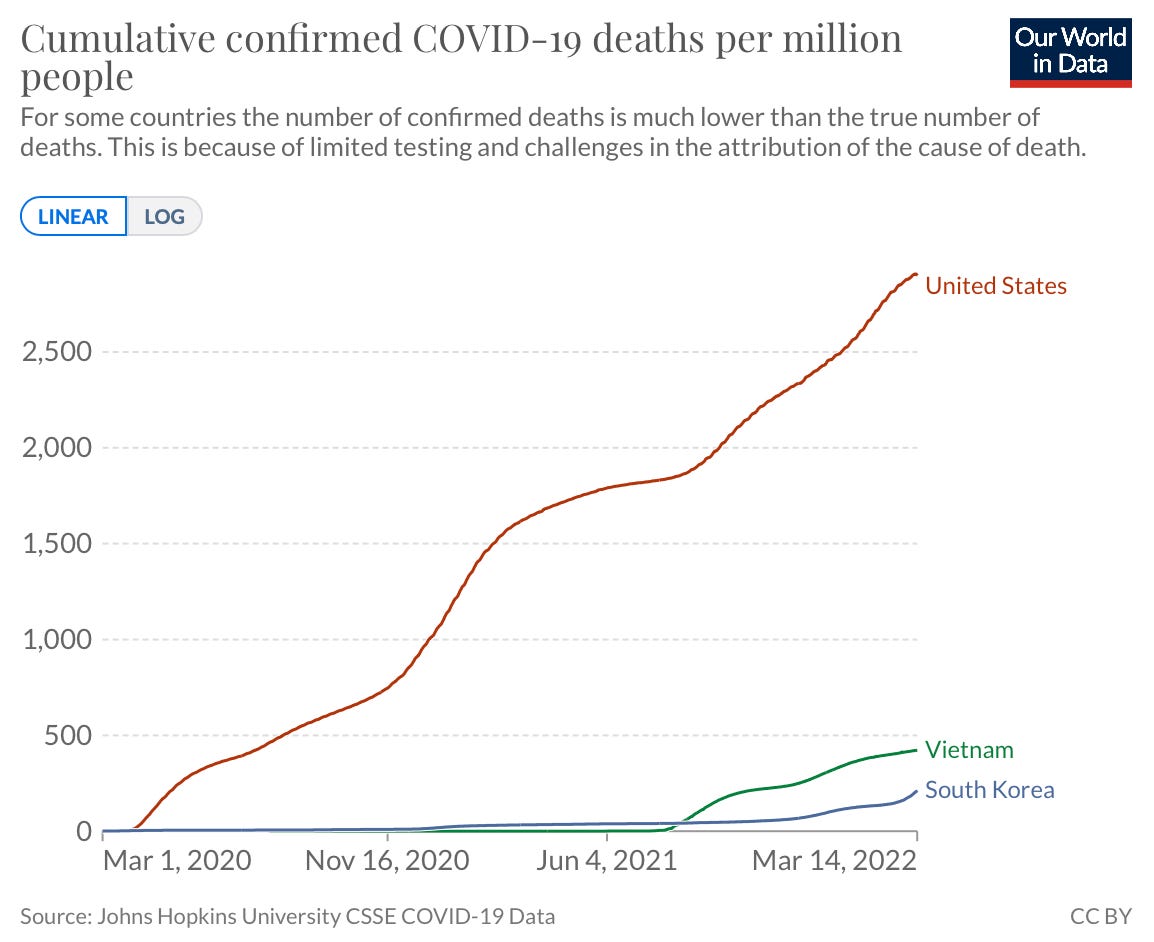

Other countries, like South Korea and Vietnam, have had very effective responses to SARS-CoV-2. This was because of the lessons they learned from previous flawed responses, like MERS and SARS. By preparing, they were able to save hundreds of thousands of lives during this pandemic.

South Korea’s lesson

In 2015, South Korea was hit with Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERSCoV) from a traveler returning from the Middle East. The South Korea outbreak involved 186 confirmed cases, 16,752 suspected cases, and 38 fatalities. All of which could be explained through 5 superspreader events and/or patient exposures across 16 hospitals. South Korea’s MERS epidemic was the second highest outside of the Arabian Peninsula. While the epidemic only lasted for 2 months, close to 17,000 people were quarantined, many South Koreans lived in fear, and the economic loss was high: ~9.3 trillion Korean won (~8.5 billion U.S. dollars).

After the epidemic, the South Korean government made 48 reforms to boost public health preparedness and response. You can read them here, as they were extensive, but briefly, the changes can be grouped into four categories:

Detection. Initial response systems, like a 24/7 Emergency Operations Center and an Immediate Response Team, to stop the outbreak of emerging infectious diseases, and to make sure that, if any type of infectious diseases break out, the spread can be prevented at the initial stage.

Treatment. A specialized diagnosis and treatment system, including quarantine facilities; increasing the capacity of testing laboratories; and funding for the development of vaccines and remedies. All of these would promptly detect and prevent the outbreak of emerging infectious diseases.

Healthcare. Improvement of healthcare facilities to reduce spread within hospitals, like more negative-pressure isolation rooms and "infection control rooms,” which involved building capacity for more beds and hiring more infection specialists.

Infrastructure. Community-based collaboration between medical centers and local governments. This included restructuring the Korean CDC.

South Korea also already had a strong backbone for these changes, with a fantastic national health insurance system and ample human resources and infrastructure.

So, when SARS-CoV-2 hit, South Korea was more than prepared. Their first case was in January 2020. They were quickly able to detect, contain, and treat all COVID19 cases. They leveraged a combination of technology and strict quarantine guidelines, but also support. For example, those in quarantine had case officers who provided food delivery, toiletries, psychological counseling if needed, and video-streaming services to keep busy. On May 6, 2020, mandates were relaxed and, by May 20, 2020 schools were back in session.

There have been small outbreaks since, but they’ve been contained. Concurrently they were also vaccinating, and today, 88% of the population is vaccinated.

While they are currently experiencing a massive case wave, cumulative deaths in South Korea are clearly differentiated from the U.S. Their preparation, swift response, and vaccination coverage has and will continue to save many, many lives in South Korea.

Vietnam’s lesson

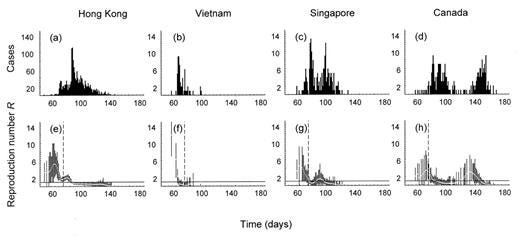

Vietnam is another interesting case example. During the epidemic of Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS), Vietnam was the second country, after China, to face SARS and one of the top four countries hit hardest. Over the course of 100 days, they had 63 cases and a case fatality rate of 8%.

After the epidemic, Vietnam stepped up its public health game to prepare for the next threat. Specifically, Vietnam increased public health expenditures per capita 9% per year. With this spending, they improved their public health infrastructure, developed an emergency operations center and improved national disease surveillance. One thing they developed was a centralized, real-time data system in which all hospitals were required to report any infectious diseases for timely epidemiological surveillance.

This investment prepared Vietnam for the arrival of SARS-CoV-2, which was first reported on January 23, 2020. Home to 100 million people and a 1,400 km border with China, Vietnam was thought to be highly vulnerable to SARS-CoV-2. But they leveraged their well invested public health system to do four things: early action, like lockdowns; contact tracing and testing; quarantining; and clear communication. Together, more than 90% of Vietnamese people reported that their government responded “very” or “somewhat” well. And, again, many lives continue to be saved because of it.

United States’ lesson…?

For decades, the U.S. has neglected public health, which left us a fragmented, outdated, and significantly understaffed infrastructure to adequately fight SARS-CoV-2. This coupled with poor communication, health disparities, poor healthcare coverage, and a highly politicized environment led to losing 1,000,000 Americans in two years. What are we doing to prepare for the future?

In the short-term, federal COVID19 funds will run out soon, as a $22.5 billion spending bill was denied last week. (There should be another stand alone COVID funding bill coming, but as NPR reported, isn’t expected to pass the Senate). This means the government can’t buy more antivirals; preventative treatments for immunocompromised need to be scaled back; funding for monoclonal antibodies will end; and next generation vaccines will be curbed. Congress must act now so we get ourselves out of this reactive public health response and move to a proactive one.

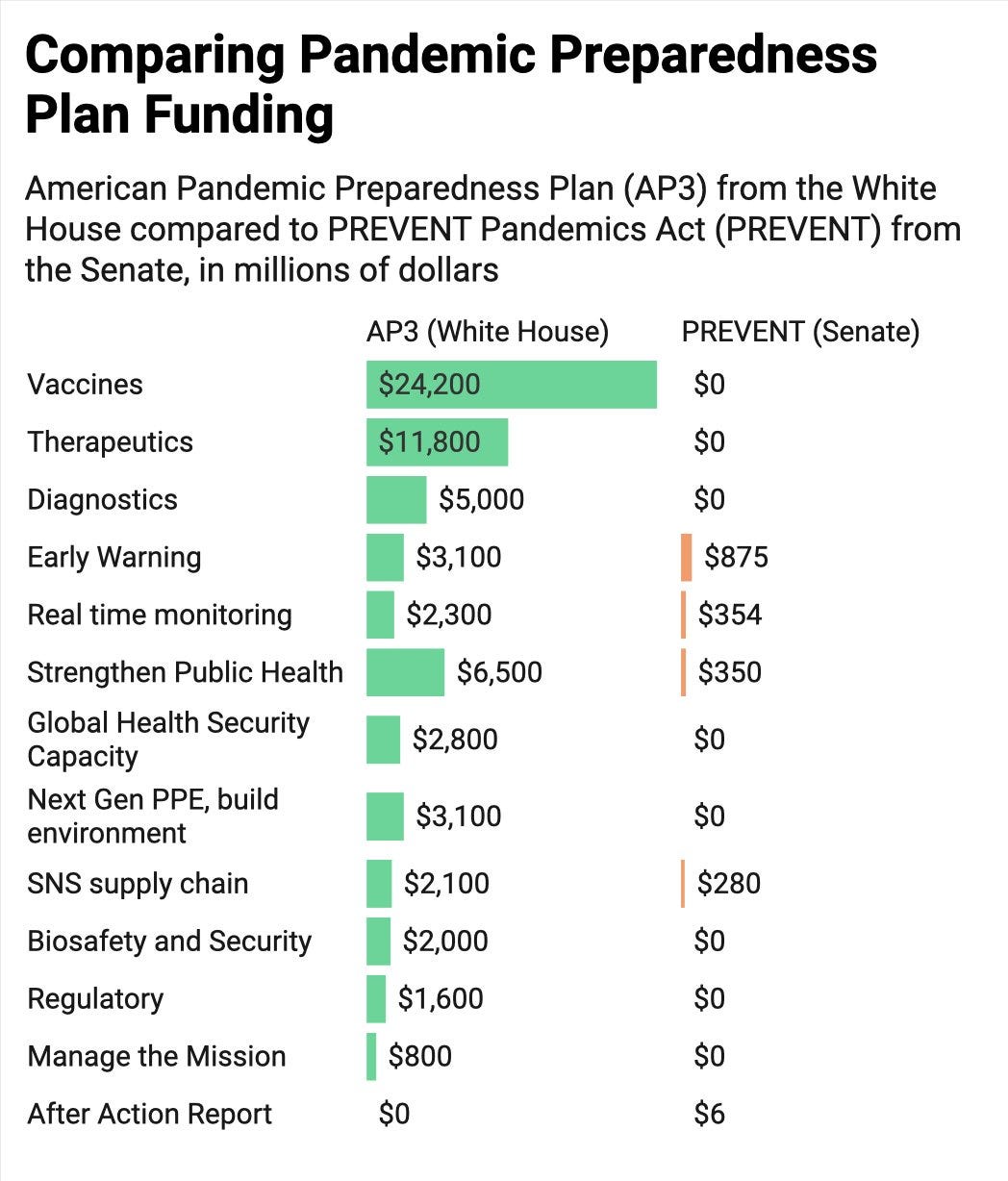

In the long-term, it does seems that the U.S. is having a conversation about pandemic preparedness. A Congressional committee met this week to discuss the new, bipartisan bill for pandemic preparedness called PREVENT Pandemics Act, which is a proposed $2 billion over 1-6 years. This comes after the White House proposed a $65 billion pandemic preparedness plan over 10 years. As you can see from the figure below, money in each category was significantly reduced and a lot of things were completely cut.

One thing added was improving public health communication and combatting disinformation (maybe Congress saw my critique last summer that this was desperately missing). PREVENT Act is also proposing the creation of an Office of Pandemic Preparedness and Response Policy. This would bring pandemic preparedness front and center at the Executive Office of the White House (and perhaps it means they will be able to request more funding down the line, too.)

Yesterday, PREVENT Act made it out of the Health, Education, Labor, and Pensions committee with amendments and a 20-2 vote. It will now go to Senate and the House.

But, is a $2 billion enough for the meaningful, long-term change that we need? As Nikki Teran eloquently said:

“The total cost of the pandemic in the United States is estimated at $16 trillion. Even if a pandemic of this magnitude only happens once every 100 years, it would be worth it for the government to spend up to $160 billion every year towards preventing the next pandemic. For reference, the US spends $175 billion each year on counterterrorism. Despite having “a 9/11 in deaths every day” for much of the pandemic, the federal government has not moved to act in even a remotely proportionate manner.”

Another epidemic on American soil will happen sooner than in 100 years, too. Since the Spanish Flu, we’ve seen new diseases emerge more and more rapidly due to climate change and globalization.

Bottom line

Forgetting about SARS-CoV-2 without preparing or investing in the future will be a dire mistake. Not only for the next SARS-CoV-2 wave but for future viruses and public health emergencies. We prepare by adequately funding short- and long- term public health responses, transforming our infrastructures, improving communication, strengthening interdepartmental, interagency coordination, and developing better surveillance systems. Hundreds of thousands of lives can be saved. We just need to learn from our mistakes, like other countries have in the past.

Love, YLE

“Your Local Epidemiologist (YLE)” is written by Dr. Katelyn Jetelina, MPH PhD—an epidemiologist, biostatistician, professor, researcher, wife, and mom of two little girls. During the day she has a research lab and teaches graduate-level courses, but at night she writes this newsletter. Her main goal is to “translate” the ever-evolving public health science so that people will be well equipped to make evidence-based decisions. This newsletter is free thanks to the generous support of fellow YLE community members. To support the effort, please subscribe here:

I feel like we're in the "gaslighting" phase of the pandemic. The "it's over" narrative is predominant, with the aid of the CDC. Personally, I've never felt more at risk. I don't see a positive solution to this public health pandemic preparation or even in managing the current pandemic. The calvary isn't coming, we're on our own. And that is very, very scary.

Appreciating these wider scope reports. Thank you!