Our excellent YLE copy editor is out this week. I think we will all live, but consider this your warning.

If you asked me— a random epidemiologist— four years ago the biggest lesson learned during a pandemic, I would have never guessed my answer today: Scientific communication. Not only the need but the how and what.

That’s because I was never trained in it. Many (if not all?) public health practitioners are not. It isn’t a core competency in our field, which became painstakingly apparent during our biggest test. It lost decades of trust.

Here’s a list of lessons I learned over the past 3.5 years.

(In case you missed it, this follows last week’s post that covered “lessons learned” more broadly.)

The Need

In Feb 2020, the WHO deemed the “infodemic” a top global health threat. Looking back, I couldn’t agree more.

Misinformation is a huge challenge, but proactive communication is even more critical. We can’t just put out fires but need to prevent them. Take people along for the scientific discovery ride.

Scientific communication needs to be separate from advocacy. That is if you want to break echo chambers.

The best and most effective comms, particularly during emergencies, are those impervious to external pressures. This is rare to find.

The How

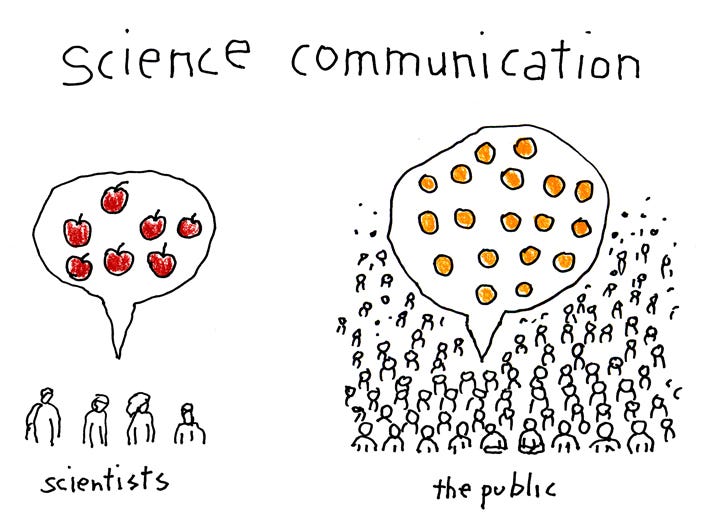

Knowledge translation is an art form—a balance between nuance and understandability. Get out of the weeds but do not underestimate the public.

People won’t listen to a concrete wall, nor should they. They deserve a face. A voice. Someone real and consistent. Give trust to take trust.

Listening is different than hearing. Communication has to be bi-directional. People have millions of legitimate questions. Find them and approach from a place of empathy.

Trusted messengers are everything. Pastors. Teachers. Clinicians. And, yes, even Trump. Translated knowledge should be diffused through massive grassroots networks.

You will get things wrong. Own it.

SciComm takes a ridiculous amount of time and energy. “A lie can go around the world before the truth gets its pants on.”

The What

Figuring out what to talk about can be tricky, but figuring out what not to talk about is even more challenging.

Anticipate needs, interests, and questions before misinformation enters the scene.

Communicating uncertainty is a must. What do you know? But more importantly, what do you not know? And how are you finding the answer?

Words matter. There’s a reason why you won’t find the word “misinformation” or “conspiracy theory” in specific YLE posts (like here or here).

Under 1000 words. Bullet points. Bold. Headings. (The book Smart Brevity changed my perspective dramatically).

Data without meaningful context are meaningless.

Always furnish solutions. Include a call to action.

Bottom line

I’m sure communication specialists are laughing at this list; none of this is new. But it is new to me. It is also new to the field. And that was precisely the problem.

I hope the field can recognize the need and urgently implement change. If not, we have no one else to blame for losing trust but ourselves.

Love, YLE

“Your Local Epidemiologist (YLE)” is written by Dr. Katelyn Jetelina, MPH Ph.D.—an epidemiologist, wife, and mom of two little girls. During the day, she is a senior scientific consultant to several organizations. At night she writes this newsletter. Her main goal is to “translate” the ever-evolving public health world so that people will be well-equipped to make evidence-based decisions. This newsletter is free, thanks to the generous support of fellow YLE community members. To support this effort, subscribe below:

Dr. Jetelina:

>YOU are a national treasure.

>So grateful for all you do to help not only public health folks, but all with specific areas of expertise to do a MUCH better job of public-facing communications.

>Every line of this is excellent, though I do have a personal favorite😎: “Under 1000 words. Bullet points. Bold. Headings. (The book Smart Brevity changed my perspective dramatically).”

Couldn’t agree more (I’m a retired editor/proofreader). I used to work with mechanical and electrical engineers, translating their work into a form the average person could understand. During the pandemic I was just going crazy because I could see what was happening: the scientists were speaking their language, politicians were speaking their language and their target audience couldn’t understand any of it. Remember the story of the Tower of Babel? Things were great until everyone suddenly started speaking different languages, then what they created fell into ruin. I believe all stakeholders (politicians, scientists, and average Americans) need to work together to create messaging that’s accurate, easy to understand, and accessible.