In December 2021, an antiviral—Paxlovid—was authorized for emergency use in the U.S. This treatment must be taken twice a day for five days and started early in the infection period to slow down viral replication. This drug was a pandemic game changer (assuming you could get it, which is another story). While Paxlovid does not prevent infection, it does prevent hospitalization and death by 90% among high-risk individuals. The verdict is still out as to whether it decreases risk among non-high-risk individuals, but initial data does not look promising.

Now that the drug has been in use for a few months, some important questions are rising to the surface.

Presence of rebounding?

During Pfizer’s clinical trial, 2% of participants who took Paxlovid rebounded. In other words, people treated with Paxlovid experienced a second round of disease shortly after recovering. But, importantly, 1.5% of participants who received a placebo also experienced rebound infections. These percentages were not statistically different from each other, so it didn’t seem like the drug caused rebounding during the trial.

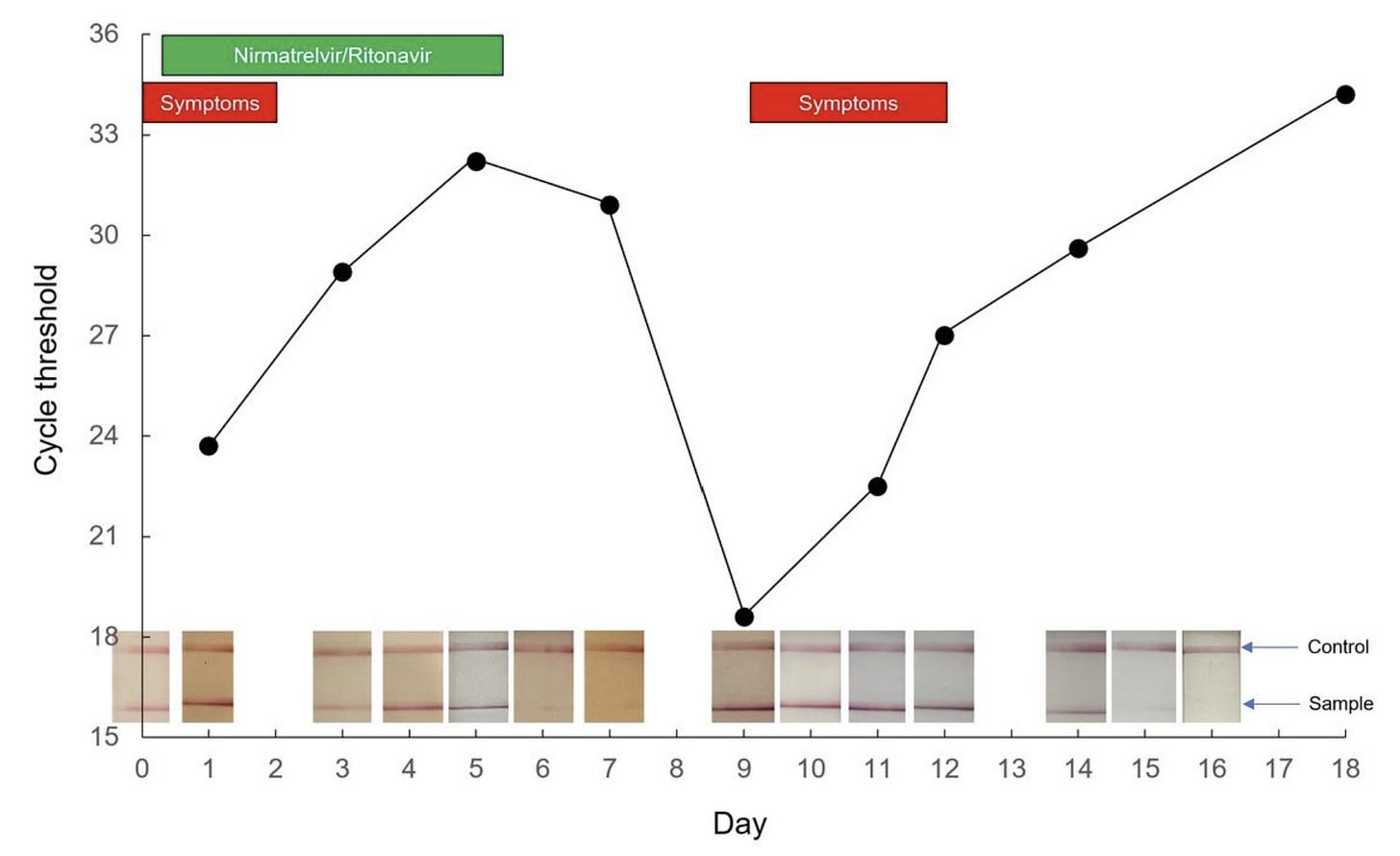

Now that Paxlovid has been in the “real world” for awhile, anecdotal evidence of rebounding is accumulating quickly. Social media, for example, is peppered with time lapse photos of positive antigen tests turning negative at the start of treatment and then turning positive again after the completion of treatment. A recent preprint also nicely described a rebound case in great detail. A 71-year-old boosted male took Paxlovid and experienced a quick resolution of symptoms. One week later, though, he developed cold-like symptoms. His SARS-CoV-2 viral load fluctuated throughout this period in parallel with symptoms, with two distinct peaks on Day 1 and Day 9 after treatment. As displayed in the figure below, the patient had a very low cycle threshold at Day 9—which can mean a very high viral load or high contagiousness.

But is rebounding occurring more than 2% of the time? We don’t know. As we’ve seen throughout the pandemic, a small percentage of a lot of people can be a lot of people. And those without Pavloxid probably aren’t documenting antigen tests as closely. This could make it seem like something meaningful is resulting from the drug when it’s not. In the same vein, scientists have reported a two hump pattern of illness among patients (with or without drugs) since the start of the pandemic. Rebounding could be just be reflecting the progression of SARS-CoV-2 disease playing out among people for whom the drug wasn’t working.

On the other hand, this could be a true signal of rebounding due to the drug that a smaller clinical trial in a tightly controlled environment unintentionally masked. It’s incredibly difficult, if not impossible, to understand the national picture due to our limited data capacity. We need numerators and denominators from a generalizable sample of a lot of people. Large, integrated hospital systems, like Kaiser, could conduct a pretty quick study, which I hope they are doing. I do know Boston researchers are already working in overdrive to analyze whether this is a true signal, too.

Why would this be happening?

If rebounding is caused by the drug, then why? There are several hypotheses floating around:

Some have hypothesized that the course of disease for individuals widely varies, so while the drug helped for the first 5 days, that isn’t long enough to clear the virus for a subset of the population. Unfortunately, we cannot predict who these people are without robust data.

Others have hypothesized this could be due to people getting the treatment too early, so the immune system doesn’t have time to mount a full response. It takes time and energy to engage our secondary responses (like B-cells), so if we take a treatment too early, they get activated after treatment is complete. And rebounding occurs.

Another hypothesis is that rebounding is occurring more often because of Omicron—a variant with a very different type of disease process than Delta (and Delta is when Pfizer’s clinical trial took place).

There’s always the possibility of reinfections, especially with such high transmission in pockets of the U.S.

Rebounding could also be due to a combination of the above, or none of the above. We don’t know yet.

Is resistance a concern?

One of the concerns with any viral relapse is the potential for drug resistance. In other words, when the virus comes back with vengeance, will it mutate to outsmart the drug? This is concerning because that mutated virus can be transmitted and the drug will no longer work, essentially making our new tool useless.

Thankfully, Pfizer evaluated this phenomenon in depth during their clinical trial. Specifically, they analyzed viral progression in 219 people (97 people in the Paxlovid group and 119 in the placebo group) on day 1 and again on day 5 of treatment. Their main goal was to evaluate if, and how, the virus was mutating and whether it was mutating to resist the drug. What did they find?

There were four places in which the virus mutated for more than 2 people. In other words, these probably were not random mutations.

One of those four mutations (called Q189K) was near the site in which the drug binds. However, the same amount of people had that mutation in the Paxlovid group compared to the placebo group. This is a good sign that the mutation is not due to the drug.

Several participants rebounded between days 10 and 14 (in the figure below, many lines started trending upwards after a consistent downward trend). And, importantly, rebounds occurred among subjects with or without mutations detected at day 1 or day 5.

In conclusion, the clinical trial found no signals of drug resistance and/or drug resistance causing rebounds. This will be important to follow, though, as with any drug.

Bottom line

After Paxlovid, a return of symptoms and test positivity may occur. Use antigen tests to determine when to exit isolation, even if you’re feeling better. In other words, test on Days 2, 3, and 4 after treatment to ensure no rebound. A good rule of thumb is that if you have a positive antigen test, you’re contagious. The FDA and Pfizer have also confirmed that those who relapse are eligible for re-treatment. This will be particularly important for the highest risk individuals, including those who are medically fragile, or those with severe rebounding symptoms.

In the meantime, scientists and clinicians are racing to find some more answers about rebounding with this new treatment. Time will tell.

Love, YLE

P.S. A special thanks to Edward Nirenberg for explaining to me some virology hypotheses.

“Your Local Epidemiologist (YLE)” is written by Dr. Katelyn Jetelina, MPH PhD—an epidemiologist, biostatistician, wife, and mom of two little girls. During the day she works at a nonpartisan health policy think tank, and at night she writes this newsletter. Her main goal is to “translate” the ever-evolving public health science so that people will be well equipped to make evidence-based decisions. This newsletter is free thanks to the generous support of fellow YLE community members. To support the effort, please subscribe here:

" This drug was a pandemic game changer (assuming you could get it, which is another story)." As an on-the-ground Familit Medicine physician working closely with Community-based organizations to fight for Equity, I would love to see a post (or series of posts) dedicated to the Inequities of COVID (which literally affects everything from access to testing and treatments, to case/hospitalization/death burden, financial/housing/food insecurity, and mental health burden), and what has worked to address them. Systemic Inequity is pertinent to each and every post. I am curious if it would be possible to speak to as a standing component to each post as well.

Isn’t it possible that the 5 day protocol needs to be extended ?