On Monday, a Florida judge voided the U.S. mandate for public transit, which includes planes, trains, and buses. Several airlines immediately announced they dropped masks. And, in true pandemic fashion, an intense debate about masks ensued.

There are health equity concerns. There are legal concerns, like setting the precedent that the CDC doesn’t have authority during a public health emergency. And there are epidemiological concerns.

In particular, I’ve noticed dangerous rhetoric around the perceived lack of transmission on planes. This misinformation stemmed from the Senate Committee hearing when several airline CEOs said “99.97 of airborne pathogens are captured by filters” so “masks serve no purpose.” While the first claim may be true, the second is not.

Here is a review of the scientific evidence.

Modes of transmission

Like I’ve written before, filtration and ventilation are powerful layers of protection against SARS-CoV-2 and other viruses. Airplanes, in particular, have fantastic systems with an estimated 10-20 air changes per hour (for context, a hospital has 6 air changes per hour). A Department of Defense report found plane ventilation and filtration systems reduced the risk of airborne SARS-CoV-2 exposure by 99%. Because of this, transmission occurs less frequently than one might intuitively expect given lots of people in close quarters with shared air. A scientific group reviewed 18 peer-reviewed studies or public health reports of flights published between January 24, 2020 to 21 September 21, 2020 and concluded that “transmission of SARS-CoV-2 can occur in aircrafts but is a relatively rare event.”

But, like any mitigation layer, ventilation/filtration isn’t perfect in stopping transmission. This is because of two things:

You need to get to the airplane, and many spaces, like crowded boarding areas, don’t have great ventilation. Also, filtrations systems are not turned on during the boarding process. One of my favorite aerosol scientists, Jose-Luis Jimenez, documented CO2 levels on his recent international plane trip. The highest CO2 level (the higher the value, the worse ventilation) was while boarding and taxiing to the runway.

Jose-Luis Jimenez Twitter SARS-CoV-2 is spread through aerosols and droplets. Filtration is great for aerosols, which float and suspend in the air for hours. But the air actually has to get filtered first. You can inhale SARS-CoV-2 aerosols before they reach the filter. Also, filtration isn’t effective for larger droplets, which can travel up to 6 feet, but then fall to the ground due to gravity. Masks help with droplets.

Proximity matters

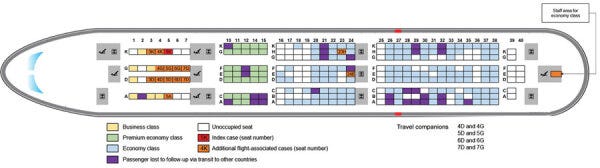

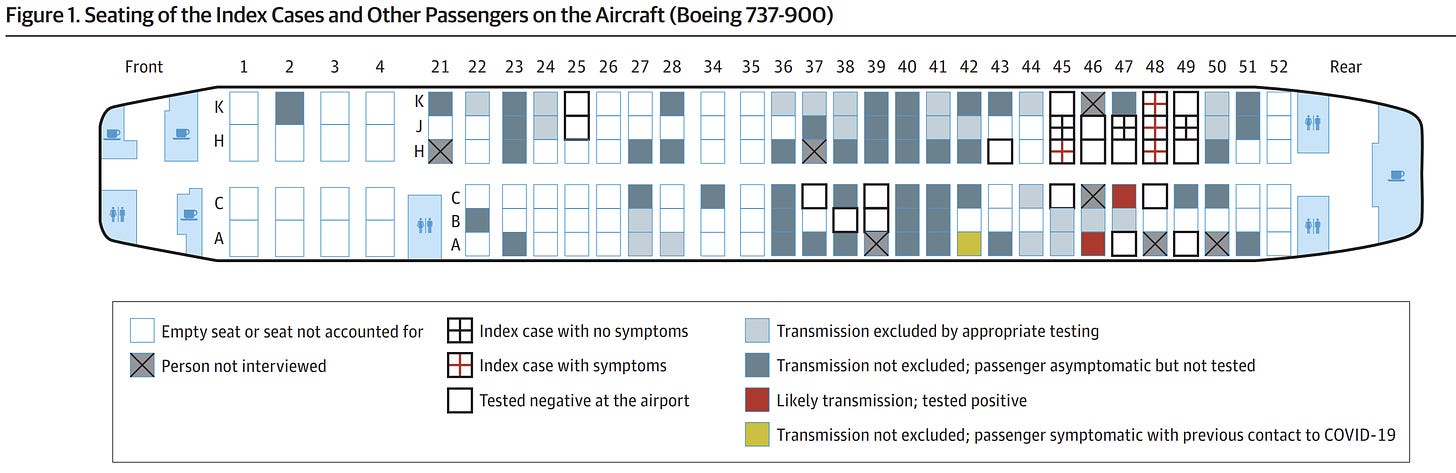

Because modes of transmission differ, scientific studies have shown that proximity to the index case (i.e., person originally infected before boarding) on a plane impacts risk of infection during a trip. A very extensive study traced all 217 passengers and crew from a 10-hour flight from London → Vietnam in March 2020. At the time, masks were not mandatory nor widely used. The index case was in business class and symptomatic (fever and cough). The scientists found 16 cases were acquired in-flight (i.e., secondary cases), 12 of which were in business class. This equated to a 75% attack rate in business class. Two cases were in economy class and another case was a staff member.

Another study assessed a flight from Israel → Germany in March 2020 with no masks. They found secondary cases were two rows away from the index case.

The importance of proximity is consistent with other viral outbreaks on planes. In a review of 14 studies, researchers found an overall influenza attack rate of 7.5%, but 42% of the cases were seated within two rows of the index case. A similar finding was documented with SARS on a flight: 34% attack rate within 3 rows of the index case compared to 11% attack rate among persons seated elsewhere.

It’s important to note that there are many examples of secondary cases not in close proximity. In the London to Vietnam study, 2 cases were not in business class, but instead 15 rows behind in economy and another was a staff member at the back of the plane. Another study found that 11 people who contracted the virus on the plane were outside the usual parameters (2 rows in front and behind).

That’s because people move a lot on planes

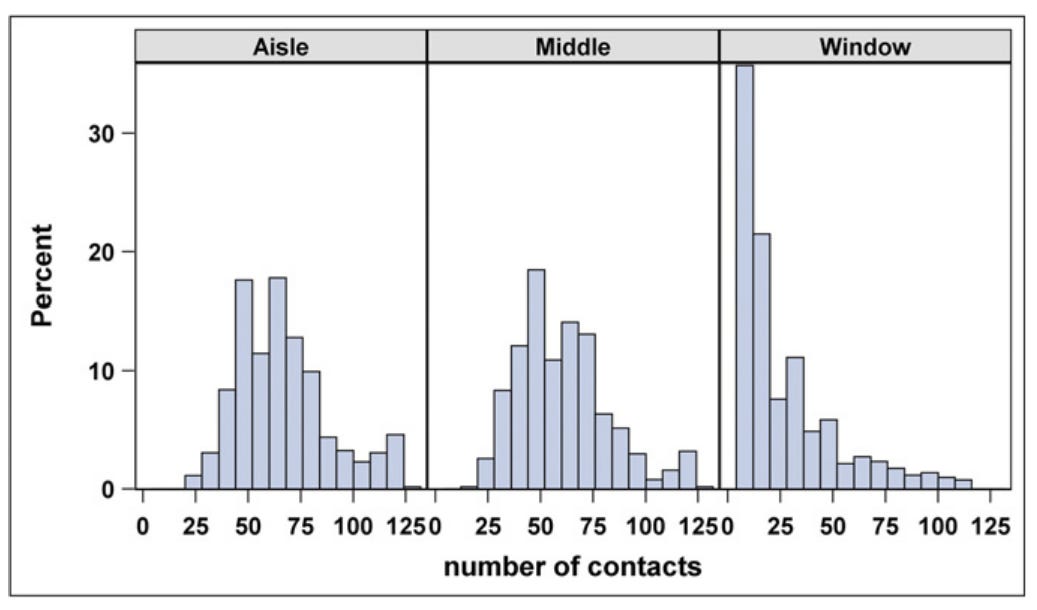

Before the pandemic, a scientific group traveled on 10 intercontinental flights to assess the behaviors and movements of people on planes and the impact on viral transmission. Of the 1,296 passengers observed, 38% left their seat once, 13% left twice, and 11% left more than two times. In total, 84% of passengers had a close contact with an individual seated beyond a 1-meter radius from them. People with the most contacts were seated in the aisle compared to the window.

One would hypothesize, then, that aisle seat passengers have a higher risk of infection. But a SARS-CoV-2 study found the exact opposite. The attack rate was higher for passengers in window seats (7 cases/28 passengers) compared to non-window seats (4/83). Importantly, the 7 window passengers said they never left their seat too. In another modeling study, scientists found that you definitely don’t want to sit next to an infected person. Beyond that, you just don’t want to sit behind them. But you may not be able to decide what seat to take.

Masks help

Regardless of where you sit on the plane, evidence shows that masks help reduce transmission. Because randomized control trials are not feasible, we’ve had to rely on descriptive and modeling studies to assess the impact of masks on planes.

In a scientific review of studies early in the pandemic, two public health reports extensively assessed transmission rates in the presence of rigid masking. The results affirmed low transmission with masking:

The first flight had 25 index cases but only 2 secondary cases. One of which was seated next to a row with 5 index cases.

On 5 Emirates Airlines (served food onboard) flights with more than 1500 passengers found no secondary cases identified despite 58 index cases

A great modeling study was published in 2021 with a few very interesting findings, too:

During a 2-hour flight with no masks, the average probability of infection was 2%. But if one sat next to an index case, the probability rose to 60%.

During a 12-hour flight with no masks, the average probability of infection is 10% (or 1 in 10). If one sat next to an index case, the probability rose to 99%.

If everyone wore high efficiency masks the whole time, the probability was reduced by 73%. If everyone wore low efficiency masks, the probability was reduced by 32%.

If face masks were worn by all passengers except during a one-hour meal service, the probability was decreased by 59% (high efficiency masks) or 8% (low efficiency masks).

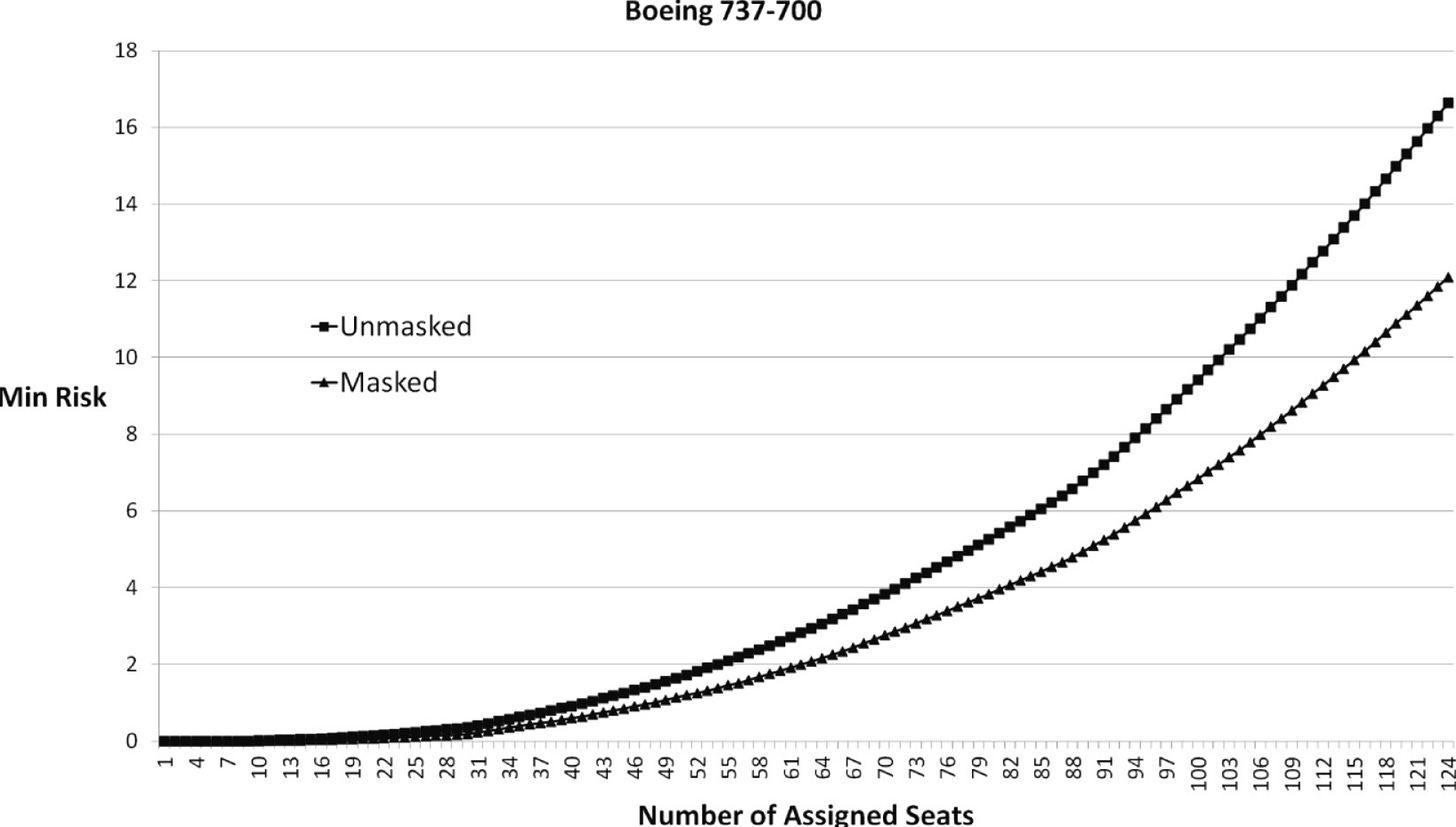

Another modeling study found the impact of masks increased with passenger count on a Boeing 737. With small passenger counts, few passengers were near each other, so mask wearing didn’t make a big impact. But as the plane filled, more passengers were forced closer together, and risk accelerated. So the impact of masks was more apparent.

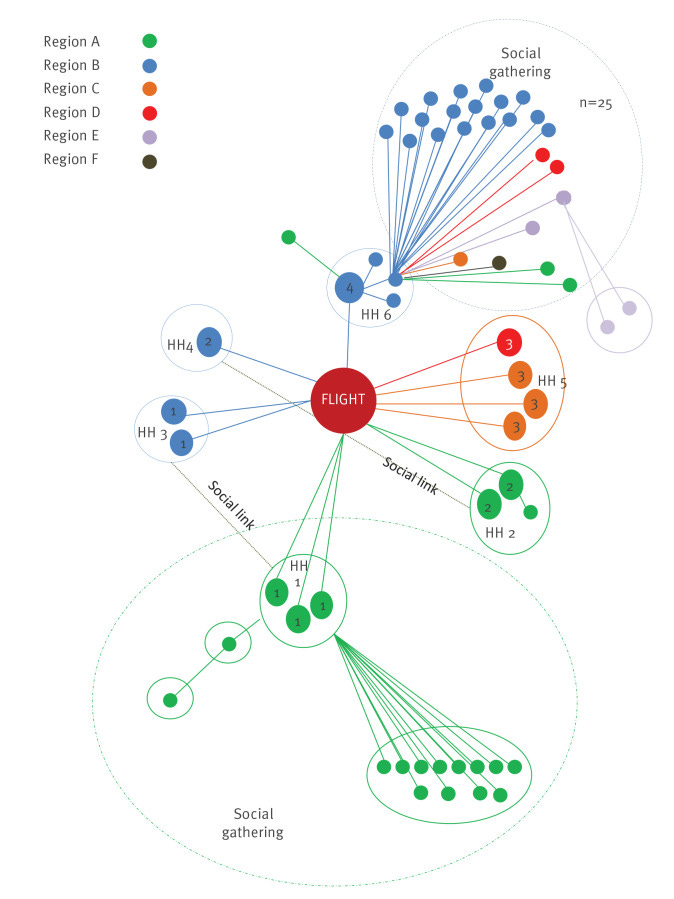

Community spread

Transmission on a plane doesn’t just impact those on the plane: infections will spill over and drive community transmission, too. One study assessed an outbreak on an international flight that landed in Ireland in the summer of 2020. Despite low occupancy on the plane, 13 secondary cases occurred equating to a 9.8-17.8% attack rate. Onward transmission resulted in spread to 59 cases in six of eight health regions in Ireland, which required national oversight.

Bottom line

Planes have great filtration/ventilation systems and vaccines are highly effective, but no mitigation measure is perfect. Wear your mask while traveling, especially with increasing case trends. The layered approach will help reduce your individual-level risk, but perhaps more importantly will help travelers who are high risk and the greater community. To me, wearing a mask is just not that big of an inconvenience for good health.

Love, YLE

“Your Local Epidemiologist (YLE)” is written by Dr. Katelyn Jetelina, MPH PhD—an epidemiologist, biostatistician, professor, researcher, wife, and mom of two little girls. During the day she has a research lab and teaches graduate-level courses, but at night she writes this newsletter. Her main goal is to “translate” the ever-evolving public health science so that people will be well equipped to make evidence-based decisions. This newsletter is free thanks to the generous support of fellow YLE community members. To support the effort, please subscribe here:

I remember when planes used to have smoking sections. Why won't airline companies at the very least offer us the choice mask/non-mask sections? I think that's fair. Anyone know anyone in the industry? Please ask them. We'd also probably get a lot more corroborating data that might at least sway some naysayers.

Just returned from the Boston Marathon on JetBlue. Thrilled to be seated next to 2 med students wearing N-95 like me!