Seeing the Forest for the Trees

What health professionals want you to know about making America healthy

I am excited to introduce a new YLE team member: Megan Maisano. She is a registered dietitian, nutritionist, and public health professional. With news of Make America Healthy Again, I know just enough to get in trouble. So, I searched for an empathetic and patient partner who can speak in plain language and is willing to separate fact from fiction for the YLE community to make evidence-based decisions. This content will be baked into the regular schedule. If you do not want to receive emails on this topic, opt out of this sub-newsletter (YLE Nutrition) by visiting your settings HERE.

There has been a groundswell of support in the past few months for making America healthier. Public dialogue on diet-related chronic diseases is important, necessary, and, quite frankly, refreshing.

But let’s be sure we don’t lose the forest for the trees. While improvements in lifestyle behaviors are necessary (and there’s a lot we can do), it’s equally important to recognize that many claims are based on falsehoods, which will do very little to move the needle. And we cannot ignore the powerful population-level forces that shape behavior. Without addressing all of these, we won’t get far.

Evidence has shown that a targeted focus on three areas can considerably move the needle on diet-related chronic disease: diet and nutrition, physical activity, and substance use.

1. Diet and nutrition

Diet is now the number one risk factor for premature death from chronic conditions (after recently surpassing tobacco use).

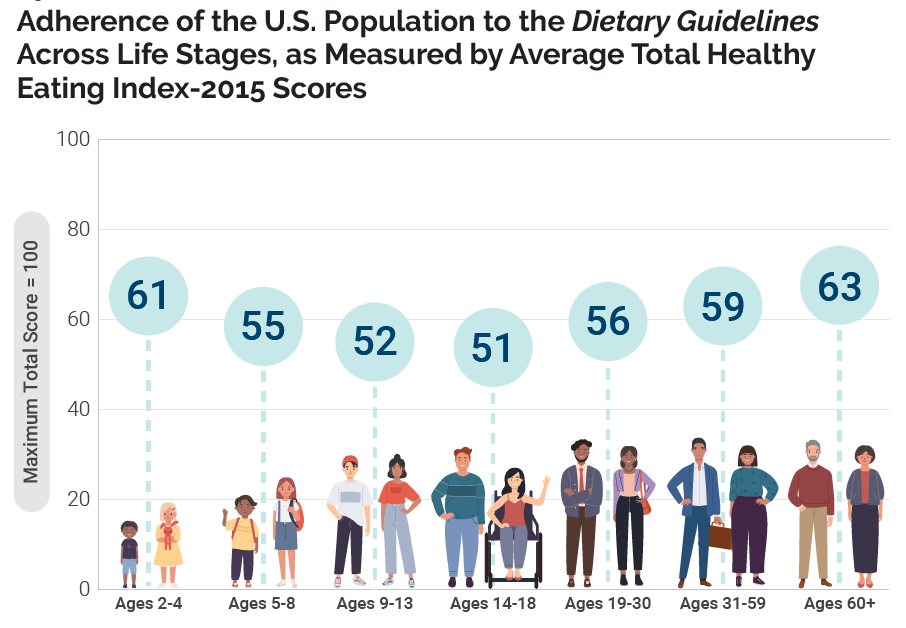

Americans’ average diet quality score is 58 (out of 100). If we increase this, there would be a lower risk of mortality, cardiovascular disease, and cancer, resulting in billions of dollars in healthcare savings.

Nearly every day, we see a headline or social media post about a food, ingredient, or chemical that’s supposedly the underlying cause of what’s making us sick. But, there are two challenges with this:

Little to no evidence that said ingredient negatively affects our health at regulated and acceptable doses.

The focus is minor compared to more important drivers of health. For example, removing artificial food colors from an already nutrient-poor processed food will have minimal effects on public health.

On an individual level, it’s best to focus on things that will actually move the needle for your health. This mainly means dietary patterns:

Most Americans exceed recommendations for added sugars, saturated fat, and sodium and don’t meet recommendations for fruits and vegetables.

Over half of American calories (~55%) come from ultra-processed food. This is not inherently bad (think frozen veggies, canned beans, and yogurt), but many of these foods are often calorie-dense, nutrient-poor, and hyper-palatable, which can contribute to lower diet quality, eating more calories, and a higher risk of weight gain.

We also have to address systemic influences on individual behavior:

Food and nutrition insecurity. 18 million American households (including 6.5 million homes with children) face food insecurity—where access to adequate food is uncertain or limited. This is not only driven by financial instability, but a complex interplay of factors such as unemployment, cost of living, race or ethnicity and geography. This often leads to nutrition insecurity, thereby affecting diet quality and health.

The food environment. While advances in processing have improved the affordability, safety, and shelf-stability of food, they have also led to widespread availability of nutrient-poor and calorie-dense food, often at a lower cost. Caloric availability per capita increased by 22% from 1970 to 2010. Today, food is available nearly everywhere. It’s rare to even check out of a hardware store without passing by snacks and candy at the register.

Lobbying. On the one hand, the industry can play an important role in public health, such as funding nutrition research (a field considerably underfunded nationally), healthy food reformulation, and commitments to hunger relief programs and national health initiatives. However, the consumer packaged goods sector (e.g., food and beverages) is still a marketplace driven by profit, so lobbying efforts can also negatively affect public health objectives such as blocking or reversing soda taxes and food labeling initiatives.

Interventions, policies, and programs such as restrictions on child marketing, industry-led food reformulation (like the FDA’s sodium-reduction goals), nutrition education initiatives, and food and nutrition service programs like school meals, SNAP, WIC, and fresh produce programs need continued effort and resources.

2. Physical Activity

Staying physically active can improve nearly every facet of our health from head to toe: our brains, hearts, bones, muscles, and weight, as well as emotional health and quality of life. Unfortunately, Americans just don’t have great statistics in this area:

The average sedentary time for Americans is 9.5 hours a day.

Only 1 in 4 adults and 1 in 5 adolescents meet U.S. Physical Activity Guidelines.

The average American spends over 7 hours a day looking at a screen.

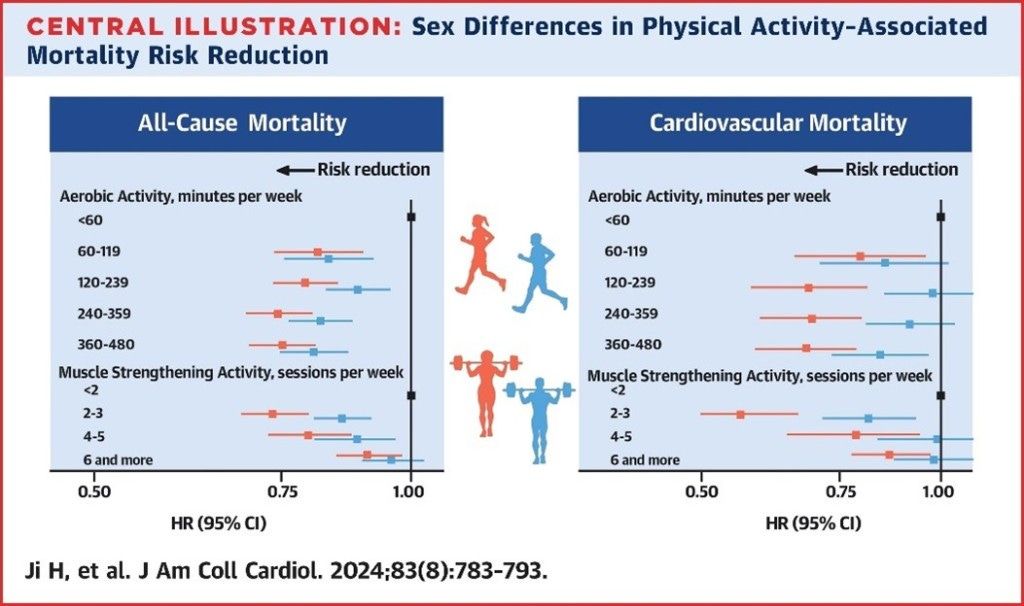

On an individual level, aiming for at least 150 minutes of moderate to vigorous activity per week appears most protective, particularly when combining aerobic activity and strength training. Any activity is better than none, and it’s never too late to start—in fact the benefits of exercise may even increase as we age. This is especially important for women as we age.

However, putting the onus 100% on individuals fails to recognize population-level forces that make it challenging to meet physical activity marks. For many, time, financial, and environmental barriers work against their ability to get adequate activity. For example, not everyone has safe neighborhoods or access to sidewalks and parks, which strongly predict a person’s ability to engage in regular physical activity.

Investments in multi-level and multi-sector approaches are key, from urban planning, public transportation, and accessible recreation spaces to adequate school recess time, walking/biking safety, and community-based policies and programs.

3. Substance use

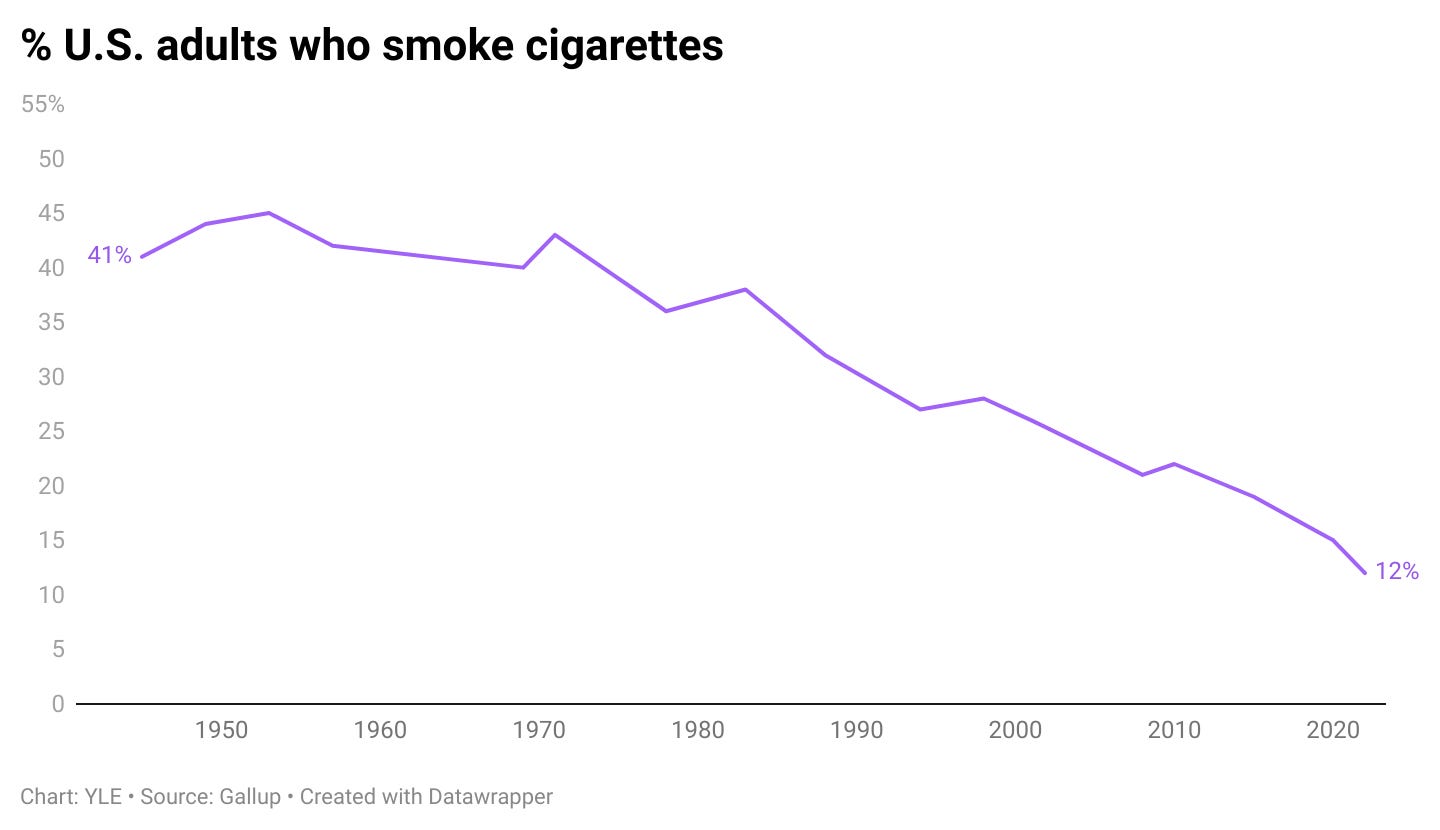

It is plain wrong to claim “X ingredient is just as harmful as smoking cigarettes.” Tobacco use remains one of the leading preventable causes of death in the United States. Full stop.

While we have made incredible public health changes in the past 50 years, there’s still a lot of room for improvement:

Nearly 1 in 5 Americans continue to use tobacco products.

Smoking kills more than 420,000 people every year.

Smoking harms nearly every single organ system in the body.

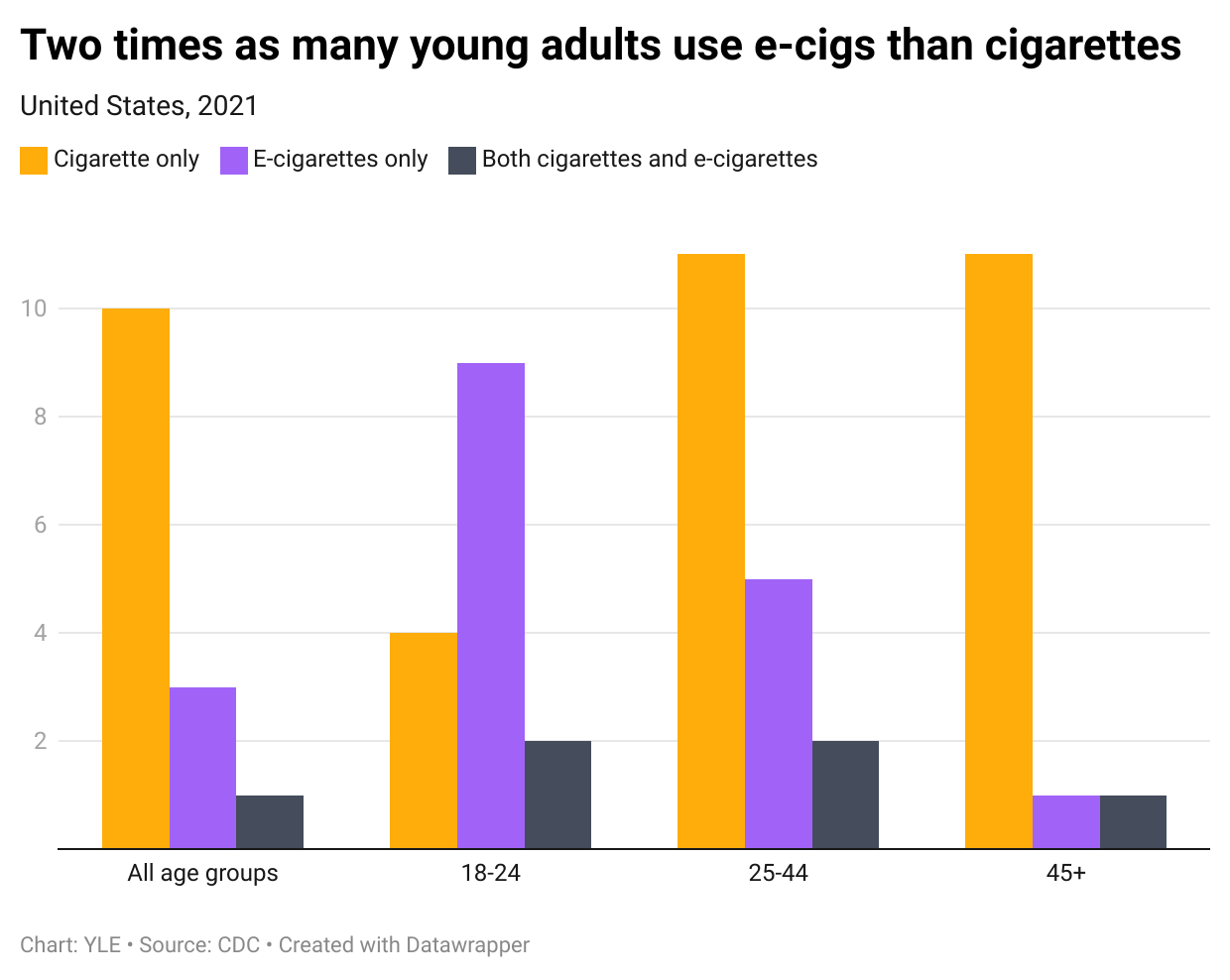

The percentage of people who vape is less (around 3-4%), but use greatly varies by age. There is a huge debate about whether the benefits outweigh the risks of e-cigarettes. It’s clear it’s most concerning among younger adults.

Excessive alcohol use also remains a public health concern.

Nearly 1 in 4 Americans reported binge drinking in the last month (4+ drinks for women or 5+ drinks for men within 2 hours).

Heavy drinking can harm nearly every system of the body, including the brain, heart, immune function, liver, and pancreas, and therefore increases the risk for several types of cancer.

On an individual level, cutting back on alcohol, even to mild or moderate intake for previous heavy drinkers, can have substantial health benefits. (There has been a lot of new science suggesting there is “no safe level” of alcohol intake, which is perhaps worth its own post.) It is never too late, and mocktails are very trendy.

Population-level strategies have made tremendous progress. These include warning labels, smoke-free places, taxes, education, and mental health services. Population strategies will continue to play an important role.

Bottom line

When entering the conversation on nutrition-based chronic disease, remember not to lose sight of the forest for the trees. Health’s basic and boring foundations don’t change much over time: nutrient-dense diets, increased physical activity, and limited substance use. Individual-level change is hard, but population-level change is even harder. Both are needed to move the needle, though. We’ve made important strides over the past century, but there’s still work to be done in our ever-evolving modern landscape.

Love, YLE and Megan

Megan Maisano is a Registered Dietitian Nutritionist. She holds a BS in psychology from the United States Military Academy at West Point and an MS in nutrition communications and behavior change from the Friedman School of Nutrition at Tufts University. During the day, Megan works at the National Dairy Council (she will not be writing about the dairy or milk industry for YLE). Megan is a lifelong learner of all things food, health, and well-being and believes “wellness” is deeply personal and should help us feel nourished and empowered, never restricted or discouraged.

Your Local Epidemiologist (YLE) is founded and operated by Dr. Katelyn Jetelina, MPH PhD—an epidemiologist, wife, and mom of two little girls. During the day, Dr. Jetelina runs this newsletter and consuls to several nonprofit and federal agencies, including CDC. YLE reaches more than 290,000 people in over 132 countries with one goal: “Translate” the ever-evolving public health science so that people feel well-equipped to make evidence-based decisions. This newsletter is free to everyone, thanks to the generous support of fellow YLE community members. To support the effort, subscribe or upgrade below:

Thank you for Megan’s addition to your team. Expert, professional health information is a bonus.

Cheers,

Michael

Thanks for the strong emphasis on population-level measures to improve health.