Over the weekend, the WHO published a much anticipated update on an unusual outbreak of hepatitis among children spanning several countries. On April 21, the outbreak resulted in the CDC releasing a Health Alert. The cause of the outbreak is currently unknown, creating quite the mystery for disease detectives.

Epidemiology

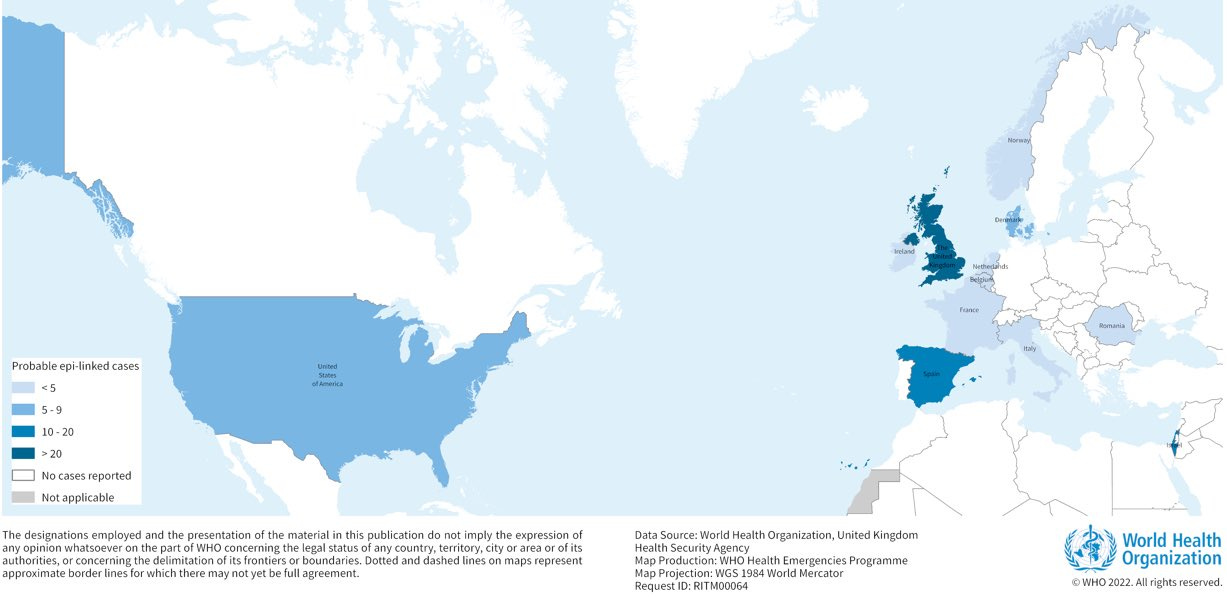

The unusual signal was first detected in the U.K. in March 2022. Since, 169 cases of hepatitis among children aged 1-16 years old have been documented across 11 countries. The majority of identified cases occurred in the U.K. (113 children), followed by Spain (13), Israel (12), and the U.S. (9). In the U.S., all cases have been in Alabama, with rumblings of another case in another state. The U.S. cases range from 1 to 6 years old.

Acute hepatitis is an infection that causes liver inflammation and damage. The severity of disease is unfortunately remarkable among these cases. Worldwide, the majority of cases have been hospitalized, 17 children (~10%) required liver transplants and at least one death has been reported. These cases do not present with a fever, but rather with jaundice, vomiting, and stomach pain. In all, an incredibly rare disease profile for healthy young children.

Investigating the mystery

Disease detectives, a subspecialty of epidemiology, have been called upon to identify the source of transmission of this outbreak. There are a number of steps they take to solve such mysteries.

First, they are tasked with determining whether this is, in fact, an outbreak: Is this a true increase in cases, or is this the expected rate coupled with heightened awareness (so more diagnoses)? Scotland health officials quickly compared the number of children with abnormal liver function tests in March 2022 to the rates in 2019, 2020, and 2021, which have an annual “background” rate of 0.52/100,000. They confirmed higher-than-expected cases in children under 5 years old, but not in older children. In fact, the number of cases among younger children in one hospital in one month exceeded the total number expected for all of Scotland for an entire year. So, this outbreak is a true signal.

Second, they rely on elimination and start with most obvious causes. In this case:

Hepatitis virus. The most common virus that causes hepatitis is, in fact, the hepatitis virus. There are five different kinds of this virus (A, B, C, D, and E), but none of the cases turned up positive.

Travel history. Gathering in-depth travel information can provide important initial clues, too. Specifically, it can point to whether these outbreaks are due to a patient zero or a virus that is more common in the community. International travel or links to other countries have not been identified as factors in these cases.

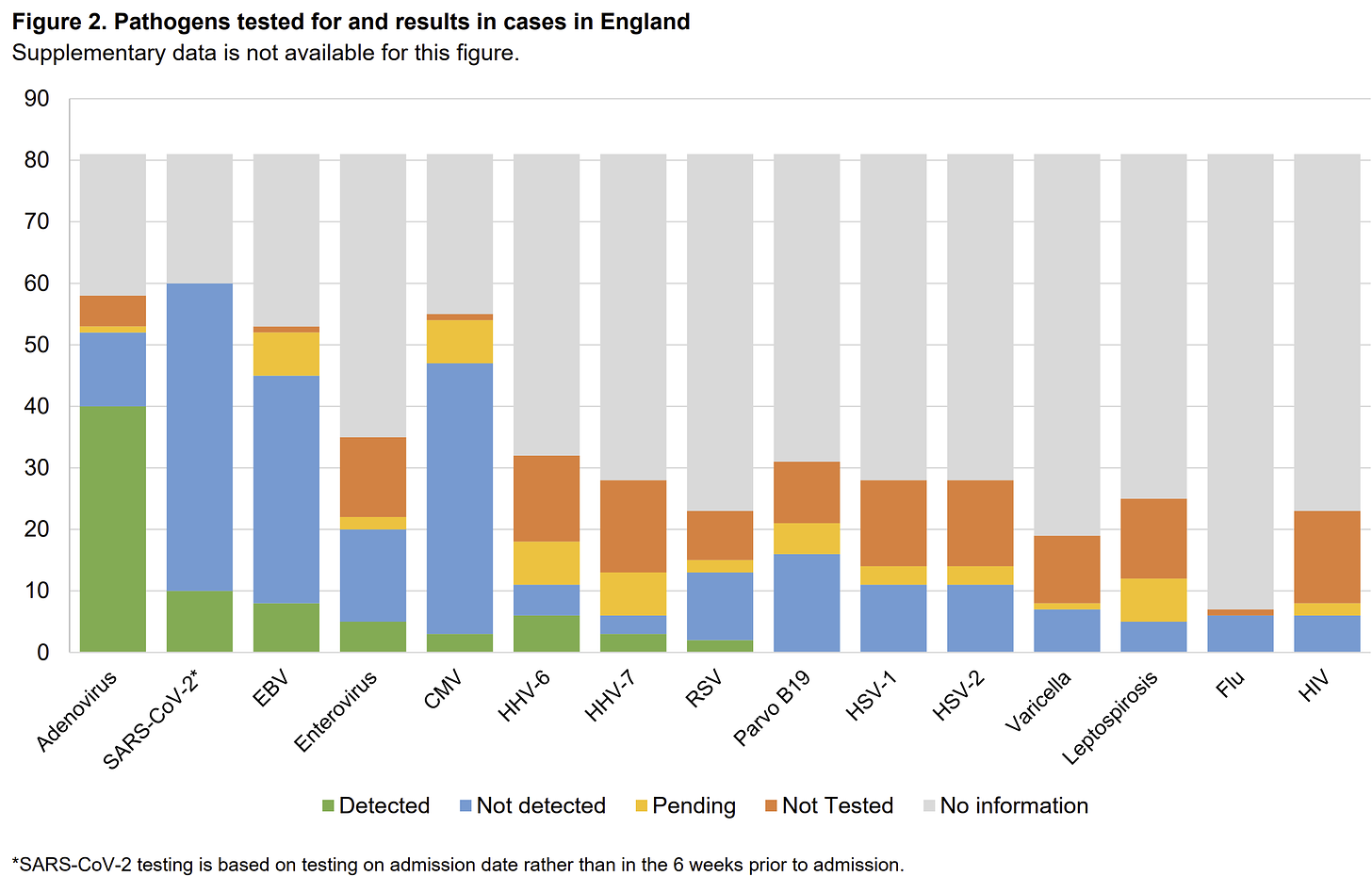

We are then left with less obvious paths. Investigating these paths takes an enormous amount of expertise and international collaboration, as it’s most useful if each case is investigated exactly the same way (so, the same labs, same questions, same sequencing, etc). As you can imagine, though, this isn’t typically done, especially in the beginning stages of outbreak investigation. So, a lot of unknown denominators can cloud patterns. This was highlighted just yesterday during a presentation at the European Congress of Clinical Microbiology & Infectious Diseases 2022 conference. As shown below, a wide variety of tests have been conducted among cases in the U.K., which makes finding patterns challenging.

Given the information we do have, there are a number of working hypotheses:

Adenovirus. One possible culprit that has floated to the top of the list is the adenovirus, as 40 out of the 53 (75%) tested cases in the U.K. were positive. In the WHO report, 74 cases tested positive (no denominator was provided). Adenoviruses typically cause colds, tonsillitis, and ear infections in children. They can also cause diarrhea. There are over 50 different adenovirus strains that infect humans, but many of these cases have been genetically identified as Adenovirus 41, which typically cause diarrhea. The adenovirus could have mutated to cause more severe disease. Or we could have a novel strain.

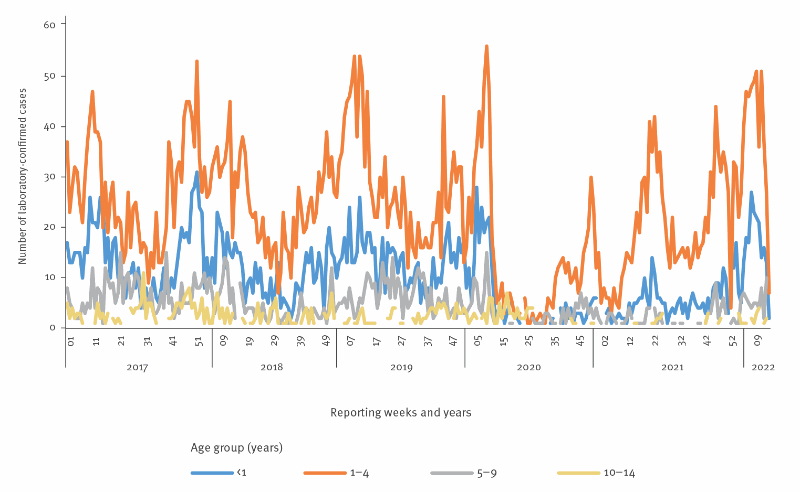

Finding the adenovirus pattern certainly doesn’t close the case, though. This virus is very, very common and, as a Scotland report displayed, on the rise. The cases could just happen to be infected—correlation doesn’t equal causation. Also, the adenovirus has DNA in its center (compared to RNA, like for SARS-CoV-2) so it can stick around much longer. The case viral loads were low, possibly indicating that the infections happened a while ago and do not explain the sudden onset of severe liver damage.

SARS-CoV-2. We can’t ignore the possibility of SARS-CoV-2 either. In an in-depth review of Scottish cases, 5 out of 13 cases had SARS-CoV-2 positive test. In the U.K., SARS-CoV-2 accounted for 16% of the cases reported compared to approximately 5-8% community positivity for the same age group. Of the cases sequenced half were due to Omicron and half due to BA.2. Most (if not all; it’s not clear) cases have not been tested for antibodies, so we can’t rule out long COVID yet. Severe hepatitis is not a common feature of COVID19, so this is an unlikely culprit but worth exploring. Other novel coronaviruses could also be the culprit.

Enteroviruses. Another possibility is a family of viruses called enteroviruses, which are also common among children. This family is most famous for polio. Virologist Dr. Angie Rasmussen thinks an enterovirus is top contender, because there are a lot of them and their diversity is understudied.

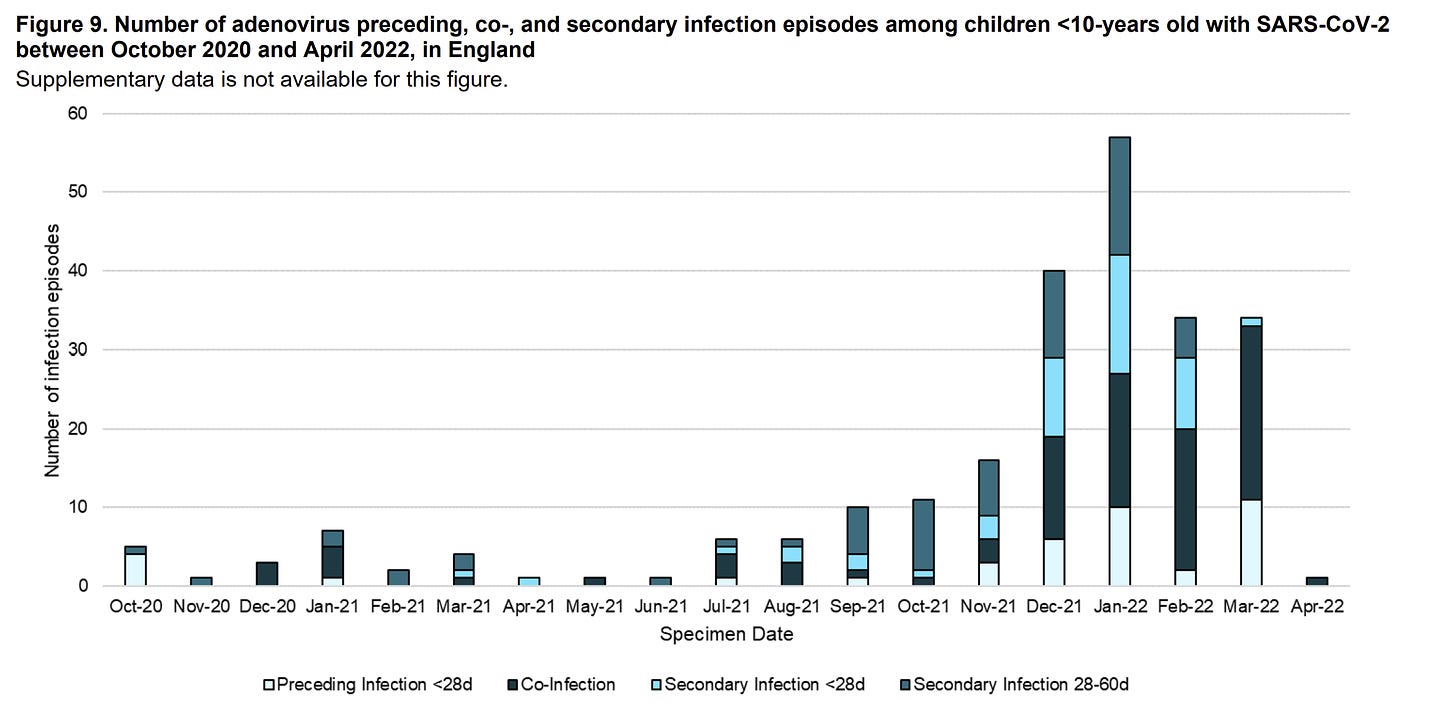

Co-infection. Then you have the complex possibility of the interaction between viruses and/or interaction between environments impacting the disease course among children. In the U.K., interactions are being explored to understand whether infection with adenovirus in the general population preceded infection with SARS-CoV-2, coinfected, or was a secondary, delayed infection. The figure below shows that co-infections are rising over time, but similar rises have been seen for other childhood infections.

Non-viral. Finally, we cannot rule non-viral causes out yet, like toxins, drugs, or environmental causes. To investigate these possibilities, the U.K. is collecting blood and urine samples from 97 of cases and comparing them to samples from 75 healthy children (controls). To date 16 controls and 11 cases have gone through analysis and nothing has been found.

Not COVID-19 vaccines. Contrary to mis/dis-information circulating the internet, these hepatitis cases are not caused by the COVID-19 vaccines. None of the cases in the U.K. were vaccinated. There is also no shedding of viruses from the adenovirus vaccine, which is also misinformation circulating the internet.

Bottom line

Epidemiologists are working in overdrive to investigate a new outbreak of severe hepatitis among children. With more knowledge will come more cases—some true signals and some not. Unraveling this mystery will, no doubt, be challenging but important so we can prevent future severe disease among children.

Love, YLE

“Your Local Epidemiologist (YLE)” is written by Dr. Katelyn Jetelina, MPH PhD—an epidemiologist, biostatistician, professor, researcher, wife, and mom of two little girls. During the day she has a research lab and teaches graduate-level courses, but at night she writes this newsletter. Her main goal is to “translate” the ever-evolving public health science so that people will be well equipped to make evidence-based decisions. This newsletter is free thanks to the generous support of fellow YLE community members. To support the effort, please subscribe here:

Thank you, thank you, thank you! I was waiting for your post on this to hit my inbox. Is it possible that covid-19 past infection lowered their immunity to an adenovirus or other virus and it’s causing more severe responses to something that used to be mild?

What a challenge! I wouldn't rule out Covid or the adenovirus possibilities. My wife had covid and has recently developed hepatic complications.,.