Shared decision-making, informed consent, and the rhetoric of false empowerment

What these medical terms mean and how they’re fueling confusion about vaccines

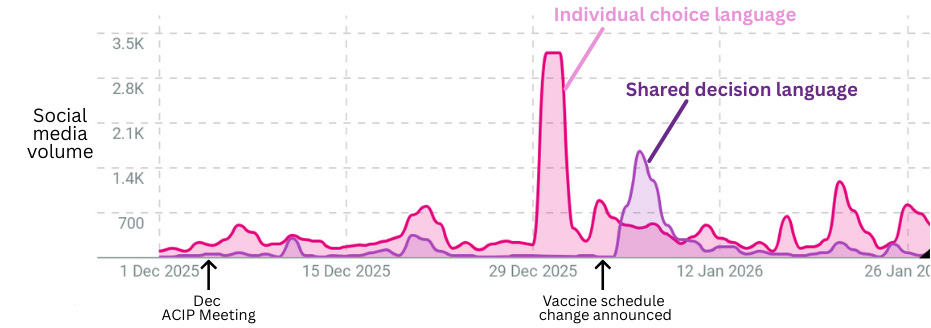

Recently, RFK Jr. made sweeping changes to routine childhood immunization recommendations in the U.S., with more changes likely to come next month. Many of these changes have centered on medical phrases such as “shared clinical decision-making” or “informed consent.” While these phrases may sound like empowerment on the surface, they’re creating confusion and obscuring what’s actually happening.

So here’s a breakdown for you: What do these phrases actually mean in the medical world? Where’s the rhetorical twist leading to confusion and distrust? And importantly, whether you're a clinician, community leader, health department, or parent talking to other parents, what's the best way to talk about this?

Shared clinical decision-making (SCDM)

What it means in the medical world: On the surface, this phrase sounds like it means “involving patients (and parents) in decision-making.” But, perhaps counterintuitively, this face-value definition is not how the phrase is typically used in the medical world. SCDM doesn’t refer to parental authority to make decisions about their child’s health—parents are the decision-makers for all their child’s health care decisions, including vaccination, regardless of the SCDM label.

Instead, when a doctor says “shared clinical decision-making,” they’re usually referring to something very specific: a situation where the medical evidence does not give one clear recommendation, and there are multiple treatment options to choose from. When that happens, “shared clinical decision-making” is how physicians approach walking the patient through the different treatment options to come to a decision.

This phrase, in medical terms, isn’t just about involving parents in decisions—it implies that no clear medical recommendation exists. It refers to this very specific situation, and typically isn’t used to describe patient involvement in decisions generally.

The rhetorical twist: Many of the vaccines on the childhood immunization schedule were changed from “recommended” to “shared clinical decision-making.” On the surface, this sounds like it’s empowering parents by encouraging them to be involved in decision-making, but again, that’s not what this phrase typically means. Instead, in medical terms, this shift in language implies that there isn’t a clear recommendation for these vaccines, contrary to the data. It gives the appearance of supporting parent autonomy while undermining vaccine recommendations. It also has behind-the-scenes implications for physicians and clinics, such as time spent charting in your medical record, ordering vaccines so they are readily available to you, automatic reminders, and more.

The communication solution: Pushing back against SCDM for childhood vaccines can easily be misinterpreted as pushing back on involving parents in decision-making. So, when talking about this topic:

Explain that parents have always been the decision-makers regarding their children’s health care, including immunizations, and changing the label from “recommended” to “shared clinical decision-making” doesn’t change that.

This means the SCDM label doesn’t actually give parents more options, but it does make it more confusing which vaccines are beneficial for their kids.

Recognize that this label is confusing to people, and has a lot of implications on the backend for clinicians and hospitals.

Informed consent

What it means in the medical world: Informed consent is the process by which patients (or parents) are informed about the risks, benefits, and alternatives of a recommended treatment or procedure. It involves the clinician explaining why the treatment is recommended, the risks and benefits, assessing the patient’s understanding, and answering questions. For certain riskier procedures (like surgery), consent is formally documented by signing a form, and for other lower risk procedures, verbal consent is obtained.

The point of informed consent is not to simply throw a bunch of information at a patient, but to ensure that the patient understands the procedure or treatment so they can make an informed decision. The goal is education and empowerment, so they are able to make reasoned decisions about their health.

The rhetorical twist: This phrase has been distorted in discussions about vaccine risks, with a push towards overemphasizing rare or unverified risks of vaccines and underemphasizing benefits. But true informed consent helps the patient understand not only what the risks are, but the likelihood of those risks and how to weigh them against the benefits of immunization. Overemphasizing rare or unverified risks distorts patient understanding of the decision, therefore undermining the process of informed consent. It is crucial that patients understand the risks in a balanced way that helps them make an overall informed decision, not a decision driven by fear.

The communication solution:

Explain that the goal of informed consent is to help patients have an accurate and balanced view of the risks and benefits of immunizations.

Distorting this balance by overemphasizing risks undermines patients’ ability to make an informed decision for their family.

Immunization requirements

What it means in the medical world: There is no universally required vaccine in the U.S. There are, however, certain locations where specific age-appropriate childhood immunizations are required for entry, mostly in places where children come together and share germs, like in schools, daycares, and some pediatrician’s offices. Recognizing that high rates of immunization is what disrupts the spread of serious childhood diseases (especially to others who are immunocompromised or too young to be vaccinated), school and daycare immunization requirements have been established by individual states to reduce the spread of disease in these higher risk areas.

The rhetorical twist: Because many of the school immunization requirements use the CDC childhood vaccine schedule as guidance, the childhood vaccine schedule has been inaccurately framed as a vaccine mandate in itself. This misrepresents the purpose of the childhood vaccine schedule, which is to provide evidence-based recommendations regarding which vaccines are beneficial for children, and when is the best time to get them based on children’s development and risk of exposure. Inaccurately reframing the childhood vaccine schedule as a mandate falsely suggests that even vaccine recommendations—not requirements—impinge on personal freedom, a distortion that hinders the CDC’s ability to make clear recommendations for children in the U.S.

The communication solution:

Explain that the childhood vaccine schedule is not a mandate.

Immunization requirements are focused on specific locations like schools and daycares due to the high risk of sharing germs in these locations.

Patient autonomy

What it means in the medical world: Respecting patient autonomy is central to the practice of medicine. Patients have a right to make decisions about their health, or as it was stated in a court decision in 1914: “Every human being of adult years and sound mind has a right to determine what shall be done with his own body.” This is one of the central principles of medical ethics, is taught in every medical school, and is paramount to the practice of medicine. Dark stains on the history of medicine such as the Untreated Syphilis Study at Tuskegee show us what happens when this principle is ignored.

The rhetorical twist: The principle of patient autonomy has more and more become blurred with a totally separate value: the idea that patients should not just be making health decisions, but that they should be doing so by themselves, without the help of physicians or experts. This rhetorical trick falsely implies that expert involvement in health care decisions—such as vaccine recommendations from physicians—interferes with a patient or parent’s autonomy merely by recommending them. This distorts what the ethical principle of autonomy is: the goal is to empower patients to understand their health (with the assistance of experts as needed) and make their own decisions, not to tell them they have to figure everything out on their own.

The communication solution:

Explain that the goal of patient autonomy is to protect patients’ right to make decisions, not to suggest patients should make health decisions without external help.

Recommendations and input from clinicians are not there to limit choice, but are meant to help patients make their own decisions by empowering them with health information and synthesizing complex evidence.

Summary

Bottom line

Patient autonomy, shared decision-making, and informed consent are foundational to medical care in the U.S. But these concepts have been twisted into rhetoric that claims to empower patients while subtly igniting confusion and driving a wedge of distrust between patients and the physicians who want to help them. This creates isolation masquerading as empowerment, and now you have some tools to spot it when it happens.

Sincerely, Dr. P

Kristen Panthagani, MD, PhD is an emergency medicine physician completing a combined residency and research fellowship focusing on health literacy and communication. She is the creator of the newsletter You Can Know Things and a regular YLE contributor. Views expressed belong to KP, not her employer.

Your Local Epidemiologist (YLE) is founded and operated by Dr. Katelyn Jetelina, MPH PhD—an epidemiologist, wife, and mom of two little girls. YLE reaches more than 425,000 people in over 132 countries with one goal: “Translate” the ever-evolving public health science so that people will be well-equipped to make evidence-based decisions. This newsletter is free to everyone, thanks to the generous support of fellow YLE community members. To support the effort, subscribe or upgrade below:

This is a top-ten YLE post for me.

This is outstanding. It should be included in medical school curricula!!