Is the U.S. in the middle of a surge? If so, how big is that surge, and what should people do? Two relatively simple questions with quite complex answers. This is mainly because we just don’t know how many “true” cases are in the community. We are flying blind due to suboptimal surveillance not adapting to our changing landscape. In all, this makes it impossible for people to make data-driven decisions.

State of Affairs

After two months of consistent nosediving, the U.S. official case numbers are showing a modest 10% increase over the past 14 days. Relative to the Delta or Omicron waves (which peaked at 164,000 and 803,000 daily cases, respectively), we are still at very low recorded case numbers, averaging 32,139 cases per day.

The Northeast is showing the most case acceleration. Rhode Island is the leader at a +94% increase in cases, followed by Maryland (+77%), Washington DC (+76%), New Jersey (+69%), and New York (+67%). There are also other random states with case acceleration, including Mississippi (+87%) and Oregon (+70%). These states may be the initial seeds needed to spark regional hotspots outside of the Northeast.

But, can we trust case counts?

Signals from the U.K. are hinting that official reported cases cannot be trusted. Professor Christina Pagel, Director of Clinical Operational Research at University College London, recently charted national daily recorded cases in the U.K. and compared to the Office for National Statistics infection survey prevalence—an ongoing study which randomly samples the community for COVID19. As shown in her figure below, before January 2022, the two metrics mirrored each other. However, recently the U.K. started to see dramatic decoupling. In other words, the national cases are severely underreported, even with the U.K.’s state of the art public health surveillance systems. In the U.K., the decoupling has been attributed to removing freely available options for testing. In addition, on January 11, those with a positive antigen test were no longer required to take a confirmatory PCR test.

Back in the U.S., we are left with even more uncertainty because we don’t have anything close to the public health surveillance system the U.K. has. However, we do know that our testing landscape is changing rapidly:

More people are using antigen tests. Thanks increased knowledge and freely available antigen tests, antigen tests are being used more than ever. A MMWR publication found use more than tripled during the Omicron wave compared to the Delta wave. While this is fantastic news, as this tool has been chronically underutilized, the CDC hasn’t done the ground work to systematically capture these cases. Thankfully, some local jurisdictions have implemented systems for the community to report at-home antigen results, but uptake is less than optimal.

Less testing. Starting March 22, providers were no longer able to submit claims for tests for uninsured patients. In other words, we removed testing incentives. Testing disparities will soon follow, if they haven’t already. As we saw at the beginning of the pandemic, the poorest neighborhoods will have even more depressed case numbers than high income neighborhoods. This will fuel a dangerous cycle of disproportionate transmission → infection → mortality.

Asymptomatic cases. With vaccines and infection-induced immunity, there will be more mild cases than ever. Because of this, there will be even more asymptomatic spread and/or people may not even get tested because they just have the sniffles and/or find no concern of being infected.

Taken together, we don’t know the true discrepancy between reported case numbers and “true” case numbers in communities. The Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation (IHME) estimates that for every 100 cases in the U.S., only 6-7 are officially recorded in our surveillance systems. For example, on March 31, 2022 IMHE reported 27,400 cases but estimated 404,600 “true” cases due to underreporting and asymptomatic infection. This gap has dramatically widened over time. During the peak Delta wave, an estimated 43% of cases were reported. During Omicron, about 26% of cases were recorded. Right now, an estimated 7% of cases are reported, which is abysmally low. We are flying blind.

This gaping distinction is most important for the public who continue to be forced to individually navigate this pandemic. And, yes, people are still, rightfully so, trying to avoid infections (it’s not inevitable) and/or break transmission chains around the vulnerable. Unfortunately, available dashboards, like the NYT and CDC, no longer accurately reflect transmission or risk to inform behavior. Even leaders are using official case numbers to drive policy decisions, like whether masks should still be required on planes. But policy is only as good as the data it’s based on.

Take Maryland, for example. Right now they are recording 8 cases per 100,000 people. According to the new CDC guidance, they are in the green because their hospitals won’t surge in 3 weeks. So, according to the CDC, you don’t need to wear a mask. According to the old CDC guidance, Maryland has “substantial” transmission with a 7-day summation of ~56 cases per 100,000. Using this metric, people are on the cusp of needing to wear a mask. If we use IMHE’s estimates, Maryland’s “true” transmission rate is much, much higher— 800 cases per 100,000— a threshold in which you should definitely, no question, wear a mask.

(To see new and old CDC thresholds for your state or county, go HERE. For new CDC guidelines—or the left figure below—select “COVID19 Community Levels” on the Data Type dropdown. For old CDC guidelines—or the figure on the right—select “Community Transmission”.)

Other surveillance systems

So if raw case counts aren’t accurate, what else works?

A lot of eyes are on wastewater surveillance. Thankfully this is implemented in many cities, but certainly not all, so it is not a generalizable or reliable metric for all areas. Wastewater detection of SARS-CoV-2 is increasing quickly across all regions of the U.S. The most movement is in the Northeast, though. We are clearly in an uptick. However, one limitation to wastewater data is that it should always be used in addition to, not as a substitute for, clinical testing data. There is no consensus on a direct comparison between wastewater SARS-CoV-2 concentration and clinical case numbers, only that they indicate similar trends. So we cannot use wastewater to then estimate how many raw cases are in an area. It can only contribute to holistic views of a virus’s spread across a community.

Test positivity rates (TPR) may still be useful, too. While there will be less PCR testing, the rate at which these PCR tests are positive and, more importantly, the trend, is still useful. On a national level, TPR is increasing and accelerating (see log graph of TPR below). However, the national threshold is still below 5%, which the WHO defined as “low community transmission” during the beginning of the pandemic.

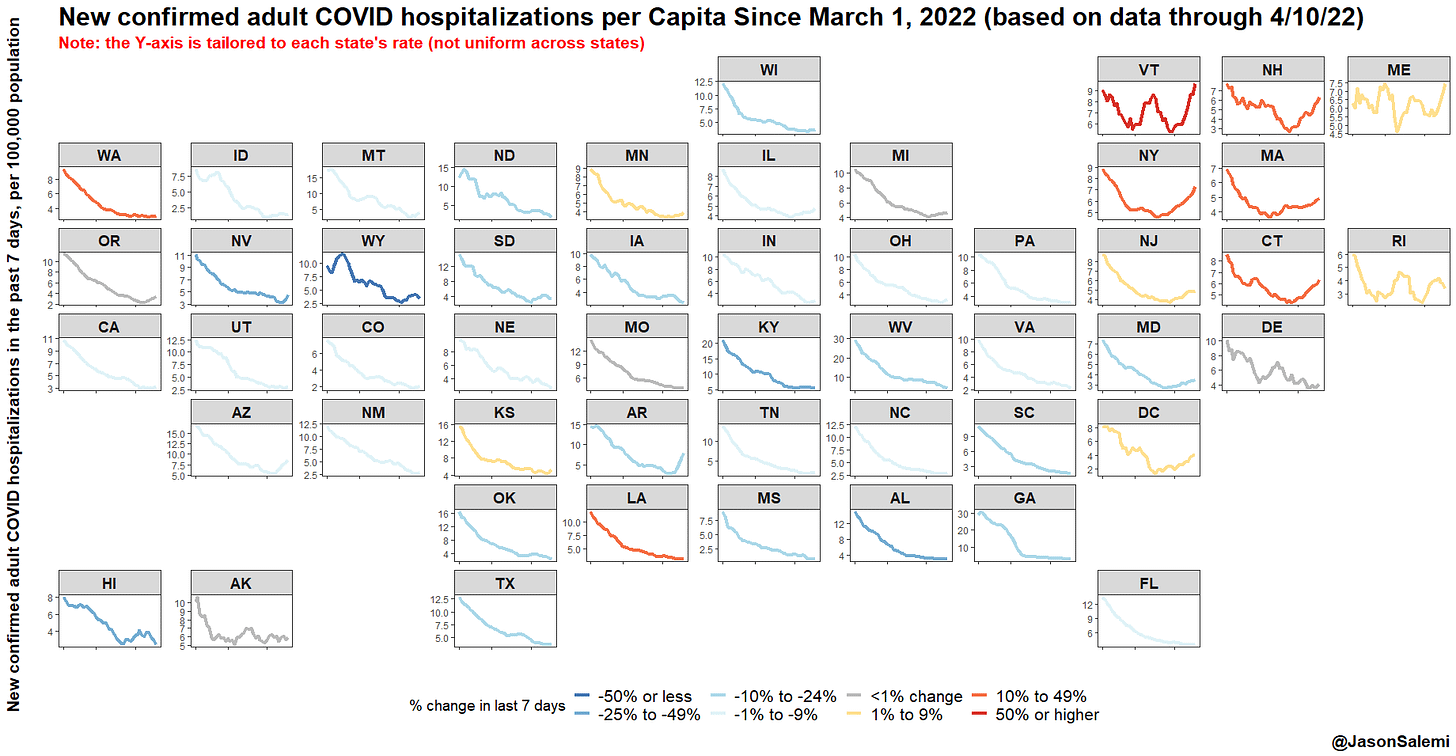

As a last resort, we can rely on hospitalizations. But this metric is lagged and by the time it increases (if it increases), transmission in the community is too high. Epidemiologist Jason Salemi nicely plotted 7-day hospital admissions, which are starting to rise in a number of states. In the majority of other states, they are continuing to decrease.

Bottom line

In true pandemic fashion, the landscape continues to shift, making it nearly impossible for individuals to navigate. Unfortunately, the reliability of case numbers is crumbling. I would urge you not to use a static number or case thresholds (like 50 cases per 100,000) to determine behavior. Instead, I would use trends— wastewater trends, TPR trends, or even case trends. If trends are increasing fast where you live, it’s time to dial up your COVID19 layers, like wearing a mask or leveraging antigen testing to break transmission chains.

Love, YLE

“Your Local Epidemiologist (YLE)” is written by Dr. Katelyn Jetelina, MPH PhD—an epidemiologist, biostatistician, professor, researcher, wife, and mom of two little girls. During the day she has a research lab and teaches graduate-level courses, but at night she writes this newsletter. Her main goal is to “translate” the ever-evolving public health science so that people will be well equipped to make evidence-based decisions. This newsletter is free thanks to the generous support of fellow YLE community members. To support the effort, please subscribe here:

What we need is random sampling

Thank you. I think possibly need to add:

4. Testing fatigue. People are tired of covid and worrying about it and testing for it. The number of people I know (in Maryland) who are sick or have sick kids but haven't tested because "it's just a cold" "covid's over, it can't be covid" "we all have allergies" is astounding. And they don't want to test for covid (just to be safe/sure) and get cranky when you suggest it.

It throws in a whole new level of "how do we negotiate this part of the pandemic".