More than 10 years ago, I moved to Geneva to work at the World Health Organization (WHO). I was a bright-eyed young epidemiologist with one mission: change the world! My job was admittedly unglamorous: sit in front of Excel, analyze HIV/AIDS drug prices across countries, and write a grueling report for each. and. every. country.

One day, I stumbled upon something shocking: one country was overcharging its citizens three times the regular price for pediatric HIV medications. I rushed to my boss; it was our moment to change the world!

We informed the country, but they already knew it was happening. In fact, the Ministry of Health was pocketing the surplus, ultimately taking advantage of helpless parents for wanting to save their child’s life. Then I learned a hard truth: We could do nothing about it. WHO works with countries, not the other way around. The WHO’s structure prevents it from holding member states accountable or acting decisively, even in situations where lives are at stake.

This story came rushing back to me this week when President Trump announced the U.S. would withdraw from the WHO, blaming the organization’s handling of the Covid-19 pandemic, systemic inefficiencies, and overpaying in dues. This was a headline-grabbing move, but the implications are far more nuanced—and important—than the politics.

The decision raises important questions about the organization’s value and effectiveness, but it also underscores its irreplaceable role in global health—despite its flaws.

Let’s not sugarcoat it: The WHO has real challenges

The WHO is a specialized agency to the United Nations. Its mission? To promote health, keep people safe, and serve vulnerable populations worldwide. This means everything from coordinating pandemic responses to setting international health guidelines to approving vaccines.

But, the WHO isn’t a typical organization. It’s made up of member states (i.e., 194 countries) represented by their Ministries of Health. While this structure allows for global representation, it also exposes a major weakness—health ministries are often underfunded and underpowered, especially in low-income countries.

And then there’s the authority challenge. The WHO Director-General might sound powerful, but they have zero authority to enforce compliance or take decisive action without the consent of member states. It’s like trying to steer a massive ship with a tiny paddle.

Then, there is a scope problem. Its scope is huge—everything from disease surveillance to mental health to non-communicable diseases. But when you try to do everything, you end up struggling to do anything really well. The result? A gap between what the WHO says it can do and what it can actually deliver.

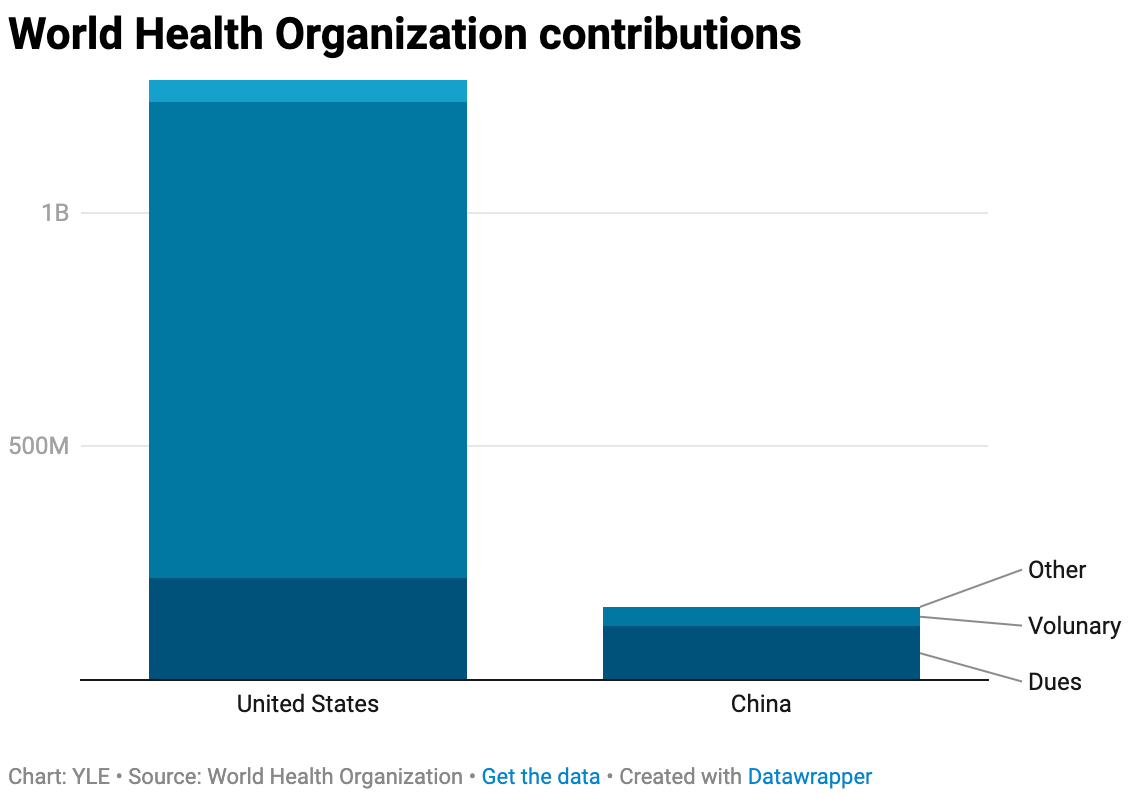

Another major challenge is funding. The WHO runs on a shoestring budget (just over $6.5 billion in 2022-2023, less than some U.S. hospital systems). About 20% of the funding comes from “dues” determined by a standard formula that considers the country’s economy. (China does pay less than the U.S. in dues, but not by much.) However, most (80%) of WHO’s budget comes from voluntary contributions by member countries that are often earmarked for specific projects. This means the WHO isn’t fully in control of its own priorities—it’s dependent on what donor countries want to fund.

Case example: COVID-19 and the WHO

Covid-19 put the WHO under a microscope. Critics argue the organization was too slow to declare a public health emergency and too deferential to China in the early days of the pandemic. China got away with a lot. Also the WHO committee on the origin of Covid-19 waffled, ultimately not making a conclusion.

Covid-19 also highlighted the gap between the WHO’s ambition and its capacity. The organization has a big voice on the global stage, but it often lacks the resources and technical expertise to back it up. This disconnect has fueled calls for reform, particularly around focusing on core capabilities.

What the withdrawal means for the U.S.

We will be “okay.” The U.S. has robust health infrastructure, its own vaccine and diagnostic certification systems, and disease surveillance capabilities through agencies like CDC. Most of what the WHO provides—certifying vaccines, technical assistance, and capacity building—doesn’t apply to the U.S.

So why does this matter to the U.S.? Three main reasons:

Self-Interest: Infectious diseases don’t respect borders. Covid-19, flu, Ebola—you name it. Even if the U.S. is well-equipped to handle its own health challenges, our safety depends on the rest of the world being equipped, too.

Geopolitical implications: If the U.S. withdraws from the WHO, it leaves a leadership vacuum. Guess who’s ready and willing to step in? China. If China dominates global health governance, it could shape international health policies in ways that don’t align with U.S. interests. Staying engaged in the WHO isn’t just altruism—it’s about ensuring the U.S. keeps the system aligned with principles of transparency and accountability. The withdrawal decision means we have overlooked using public health as a diplomacy tool.

Being a good neighbor: As a wealthy nation, it’s our responsibility to lift others.

So, is this the end of the world?

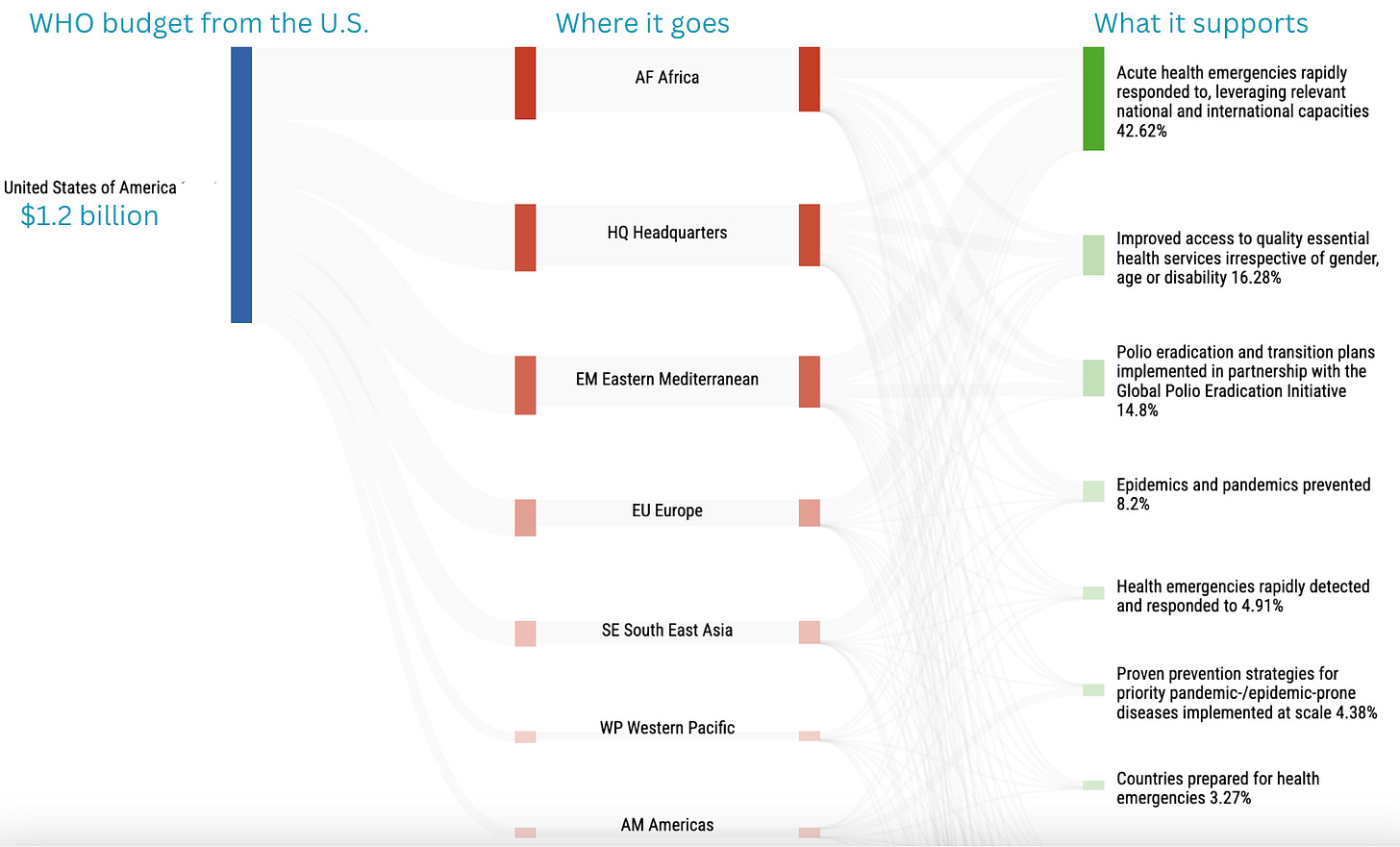

No, but this will make things a lot harder. The U.S. is the single biggest donor to WHO, giving $1.3 billion annually and beating Germany, the second-place donor, by hundreds of millions of dollars. Most U.S. money goes to WHO Africa, Headquarters, and Eastern Mediterranean, but no region is untouched.

The WHO, for all its flaws, is the backbone of global health coordination. Without it, we’d have no centralized system to manage cross-border health threats. And, for many low-income countries, the WHO is all they have.

Implications are stark:

For low-income countries: The WHO often provides the only technical assistance and resources these countries have. Losing funding will be devastating to their health and biosecurity.

For disease surveillance: The WHO coordinates global surveillance system for diseases, like influenza and polio. This helps countries prepare vaccines and track emerging threats.

For vaccines and diagnostics: The WHO certifies vaccines and diagnostics, like rapid tests, for use in low- and middle-income countries. While the U.S. has its own systems for this, many countries rely on WHO certifications to access life-saving tools.

For global health leadership: Americans working at the WHO are forced to come home, leaving a leadership vacuum in global health.

Where do we go from here?

The WHO is far from perfect, but it’s the best tool we have to tackle global health challenges. Reform it? Yes. Abandon it? No.

There isn’t any real value in us pulling out. Yes, we will save 1 billion dollars, but this is peanuts compared to the downsides. Rather, personalities need to be put aside, and reform is needed. The U.S. and other member states should push for:

Refined scope.

Sustainable funding, including reducing reliance on earmarked donations and increase flexible funding.

Stronger leadership: Give the Director-General more authority to enforce compliance and take decisive action during crises.

While it’s not too late to reform, it doesn’t look like it’s the direction the U.S. is going.

Bottom line

The WHO plays a vital role in global health, particularly for countries that lack the resources to respond to crises on their own. Reforming the organization is a long-term project, but it’s worth the effort. In an interconnected world, health threats don’t respect borders.

During my time in Geneva, that one country never changed. But because of our work at WHO, the surrounding countries received more financial support so the children could get access to cheaper (fairly priced) drugs, and, in turn, their lives were saved. The public’s health is a team sport.

Love, YLE

Your Local Epidemiologist (YLE) is founded and operated by Dr. Katelyn Jetelina, MPH PhD—an epidemiologist, wife, and mom of two little girls. YLE reaches more than 305,000 people in over 132 countries with one goal: “Translate” the ever-evolving public health science so that people will be well-equipped to make evidence-based decisions. This newsletter is free to everyone, thanks to the generous support of fellow YLE community members. To support the effort, subscribe or upgrade below:

Can you address the abrupt silencing of the of all US pubic health, the cancelling of all NIH activity, the cancellation of ACIP--while international global health is important, this internal gutting of domestic public health is terrifying. Any information on your end?

Yet another quitting that will end up harming us in the long run. And to think we could have just given WHO a few $Trump meme coins, or Melania coins, or sold some sneakers and bibles to keep the US funding going. The billionaires in the second row could have stepped up with pocket change too.

But it’s more about controlling the world health narrative, the fictional stories, and having convenient fall guys for the first administration’s Covid failure.

Cool that you worked there! I’m guessing we will be back in 4 years.