I was going to wait until next week to start writing about firearm violence. During the day, I’m a violence epidemiologist so have some perspectives to share. But this week has been a lot. People need time to grieve, to react, and to process, so I was going to allow space for that. But I’m starting to see dangerous rhetoric bubble to the surface: We can’t change this; we won’t change this; and, there is no hope. I’m here to say that is false. We can reduce gun violence in the U.S. And we will. We do this by treating firearm violence like the public health issue it is.

Previous successes

Sometimes changing behavior or culture seems impossible. But it can be changed through a public health approach.

During the 1960s, for example, it seemed impossible to change tobacco use. The tobacco industry had one of the strongest lobbies in history, smoking was part of our every day lives, and people were addicted. But it needed to change. We were getting more and more evidence that tobacco causes lung cancer, and we started unpacking the dangers of second-hand smoking. So we treated it like a public health issue. And we did this not by banning tobacco, but through a consistent and coordinated effort of approaching the public health problem from multiple angles. We launched massive education campaigns, we put warning labels on tobacco cartons, we passed policies (like non-smoking and smoking areas), we found ways to help people curb addiction, and much more. This led to a decline in tobacco use of approximately two-thirds in the more than 50 years since the first Surgeon General’s report warned of the health consequences of smoking. In 2018, cigarette smoking among U.S. adults reached an all-time low of 13.7%.

Motor vehicle fatalities also seemed impossible to change. In 1913, 33 people died for every 10,000 vehicles on the road. But we knew we didn’t have to accept this. So we made public health changes. We didn’t ban cars, but we rather made cars safer (e.g., blinkers, technology like backup cameras and warnings), we made drivers safer (e.g., seatbelts and airbags), we made passengers safer (e.g., invented car seats), and we launched massive education campaigns. We made small, incremental changes that added up. In 2020, the death rate was 1.53 per 10,000 vehicles, a 95% improvement since 1913.

Most recently, COVID19 seemed impossible to conquer. It was a novel virus, it was out of control, and it was killing many in its wake. But we leveraged all disciplines of science and industry, we invested in innovations, we fought mis/disinformation through grassroots efforts, and much more. As a result, we saved 1 million lives with COVID19 vaccines in the United States. This was an unprecedented public health success. We will never reach zero COVID19 deaths, but we can continue to inch our way closer by improving our public health infrastructure, continuing education and communication, and developing better tools (like second generation vaccines).

All of these problems were treated as a public health issues, and we made unimaginable progress by combining science, education, policy, advocacy, and innovation.

Moving the firearm needle

It’s hard to see that we’ve made some progress with firearm violence, but we have. The idea that nothing will change because we've seen this before is just not true. After Parkland, a wave of advocacy by high school students resulted in 19 states (including FL) and DC passing extreme risk orders, which have saved lives. After Sandy Hook, Connecticut passed a permit law that has saved lives, and other states also took action, including Maryland, New, York, and Colorado. While proposals tend to fall short, they make progress and inch us forward to a safer world.

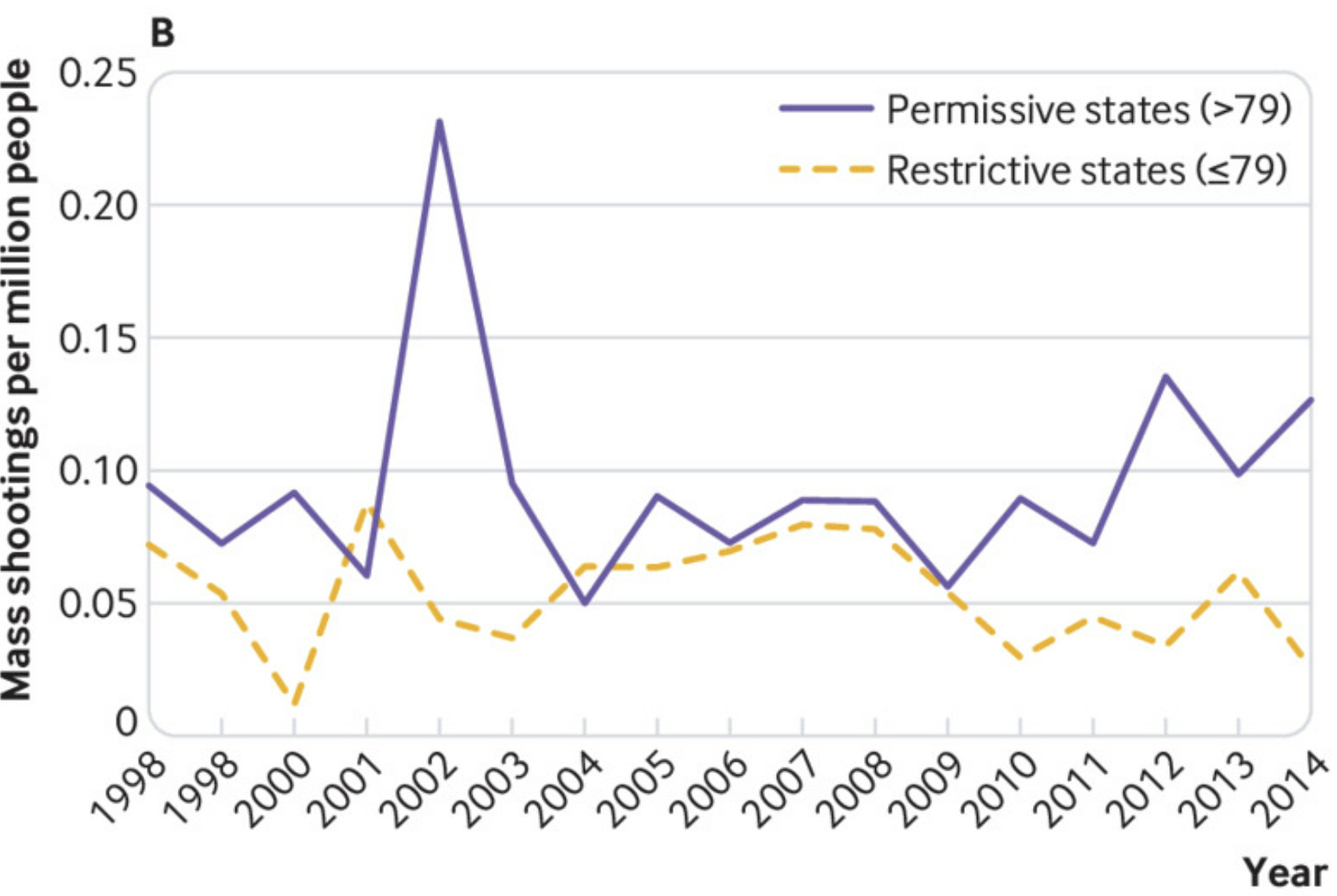

On a state level, we see the positive impact of more restrictive laws. A recent BMJ article found that states with more restrictive laws have reduced the rate of mass shootings. This was the case even after accounting for other state-level factors that could explain the relationship, like income, education, race, female head of household, poverty, unemployment, and incarceration rates. There is also a growing divide emerging between restrictive and permissive states, as you can see in the figure below.

But even if states don’t pass policies, this doesn’t mean we are out of luck. There are a number of public health interventions we can still implement:

Investing in data surveillance. One of the lowest hanging fruits is to make our data systems better. Bad data makes bad policy. We need to have a comprehensive understanding of the patterns to make data-driven, evidence-based decisions for populations in need.

Safe storage (making sure that your gun is locked up and not accessible to others) is one of the most important things that we can do to reduce risk of firearm suicide and homicide, especially among children. One study of firearm violence showed that 82% of children used a firearm belonging to a family member, usually a parent. But many parents don’t think this is an issue because they think their firearms are hidden well-enough away. In another study, among gun-owning parents who reported that their children had never handled their firearms at home, 22% of the children, questioned separately, said that they had. We can educate parents, and we can provide places to store in the community. We can move this needle. And gun owners can help. In fact, I am currently conducting a study with colleagues in which we are working with gun ranges and gun stores to help educate at point-of-sale. They want to help and are incredibly engaged and providing solutions we would have never thought of.

Leakage is another example of a potential public health solution. Among mass shooters, 44-50% leak their plans through social media or by telling friends or family. Among school shootings, more than 78% of mass shooters leaked their plans. Leakage can be a critical moment of intervention to prevent gun violence. If we increase knowledge about leakages (what to look for, what’s harmless vs. harmful) and create opportunities to report threats of violence, we may be able to prevent some mass shootings. Some fantastic networks have already been established like Say Something, which was created after Sandy Hook.

Funding. There are many, many more interventions that have the potential to reduce mass shootings, as well as other firearm injuries like suicides and accidental injuries. However, researchers and public health agencies need the support to rigorously explore innovative and effective solutions. After decades of no funding (read the frustrating history on my previous post), in 2020—for the first time in 25 years—our federal budget included $25 million for the CDC and NIH to research gun-related deaths and injuries. While this is a great step, it isn’t enough. A 2017 study estimated that we need $1.4 billion to curb the firearm epidemic as a whole (mass shootings as well as suicides, homicides, and unintentional injuries). For context, the NIH gets $6.56 billion allocated for cancer research.

We also know there are a number of things that don’t work. For example, we know solutions based in reforming the mental health system will not achieve the intended results for mass shootings (I’ll go more into this next week). Other solutions may do more harm than good, like active shooter drills at schools. We need to be data-driven, evidence-based, and, most importantly, work with stakeholders in the community so when we do have potential solutions, they are implemented with high buy-in.

Bottom line

We’ve been able to do unimaginable things and save millions of lives when we approach problems with a public health lens. We need to mourn this tragedy, but don’t lose hope. Change is possible, and we need to fight for it.

I’ll be back next week with more statistics and more on what the science shows. Take care of yourselves and your loved ones this weekend.

Love, YLE

In case you missed it, previous posts include:

“Your Local Epidemiologist (YLE)” is written by Dr. Katelyn Jetelina, MPH PhD—an epidemiologist, biostatistician, wife, and mom of two little girls. During the day she works at a nonpartisan health policy think tank, and at night she writes this newsletter. Her main goal is to “translate” the ever-evolving public health science so that people will be well equipped to make evidence-based decisions. This newsletter is free thanks to the generous support of fellow YLE community members. To support the effort, please subscribe here:

Thank you so much for your positive perspective on gun violence, Katelyn. I was one of those people who just threw her hands in the air and said "there's no hope" with our divided political landscape. I forgot that there were other avenues to try. Have a happy holiday weekend. And rest - you need it.

I welcome your data-driven perspective. Hope has been in short supply; thank you for providing some.