As measles cases increase, online rumors follow. Encased in some recent rumors is the underlying assumption immigrants— especially illegal immigrants from the Southern border— are fueling U.S. measles outbreaks.

Where is measles coming from?

Measles has to be imported

Measles was eliminated in the U.S. in 2000, which means measles isn’t just randomly floating around the community. Measles has to be imported, find an unvaccinated pocket, and spread.

This is easy for measles to do, given three things:

Globalization. A virus is just a plane ride away.

Contagiousness. Measles is one of the most contagious viruses on Earth.

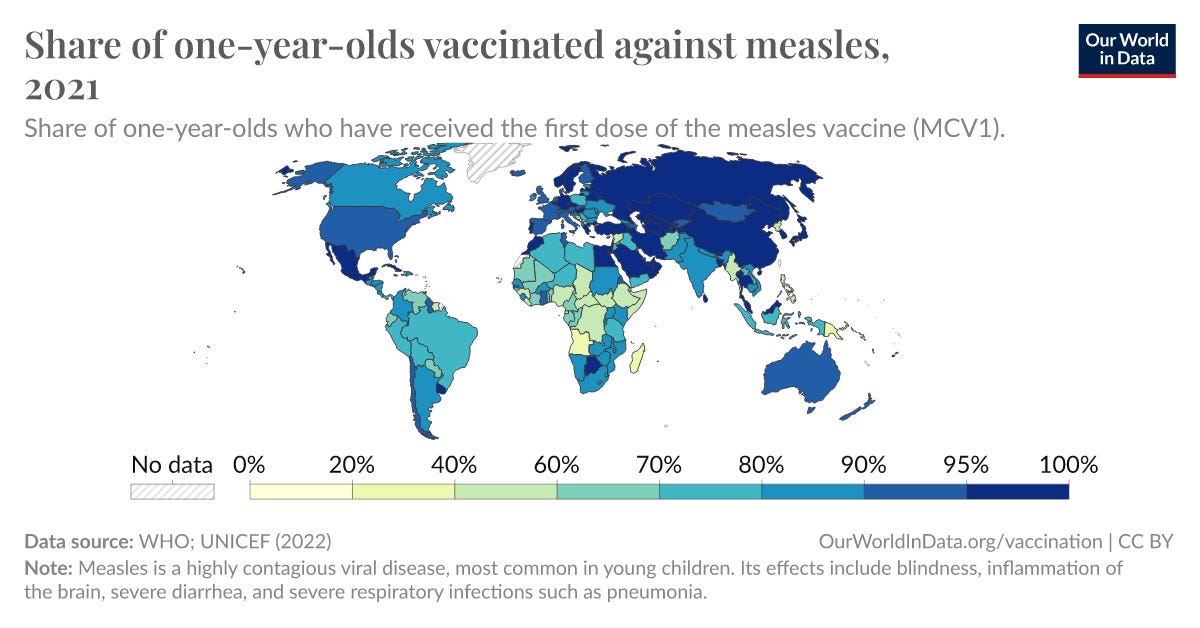

There is a lot of measles out there. Many countries don’t have access to vaccines or are highly distrustful of institutions (and thus vaccines). Plenty of countries have less than 70% measles vaccination rates.

The Americas are pretty well vaccinated. Some countries, like Mexico, have higher vaccination rates than the U.S.

Most cases are U.S. residents traveling abroad

Health departments investigate every measles outbreak to prevent it from spreading. They ask people all sorts of questions to understand where the virus has spread and who needs to quarantine. This is called contact tracing.

If we aggregate contact tracing data, as scientific teams have done in previous years, this is what the data tells us:

In 2019, our last bad measles year, 77%* of index cases (i.e., patient zero for an outbreak) were U.S. residents who had recently traveled and returned home infected. The top source countries were the Philippines, Ukraine, Israel, Thailand, and Vietnam.

The massive 2019 New York outbreak among the unvaccinated Orthodox Jewish community started when a child picked up measles on a trip to Israel and returned home.

In 2015, the previously bad measles year, CDC reported 159 measles cases—155 (97%) were U.S. residents, and 4 were foreign travelers. The source regions were the East Mediterranean, Asia, and Europe.

In 2011, 3 out of 4 index cases were U.S. residents returning from abroad. 1 out of 4 were foreign travelers.

What about this year?

Although the data above is getting old, and although we’ve seen an increase in immigration in the past few years, we have no reason to believe this year is different from others regarding measles transmission.

This is what we know:

The majority of outbreaks in 2024 are from confirmed travelers (no surprise). We don’t know their citizenship.

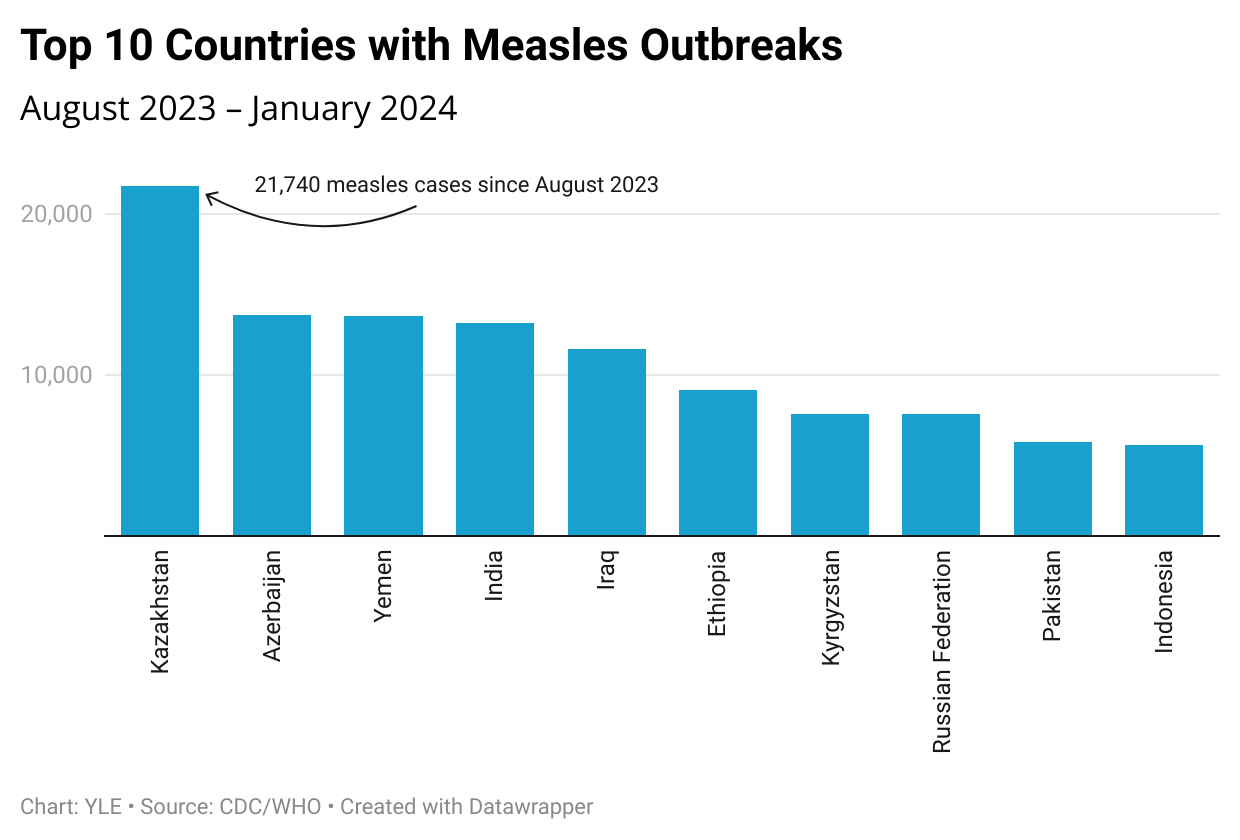

Thus far, cases have come from places with active outbreaks. CDC doesn’t name the countries, but below are the top 10 countries with measles cases.

While the most recent Chicago outbreak spread within a migrant facility, the index case didn’t come from the shelter. Measles was just able to find the shelter, which was a huge unvaccinated pocket with ~50% not having the MMR vaccine.

Why don’t we know more? Details are, admittedly, very hard to find. This is likely all the public will get regarding details in real-time. Public health has to play a very careful dance with reporting:

Provide enough information about cases so that people can protect themselves (i.e., was there a measles case at this grocery store at this time, etc.).

Don’t provide too much information such that people can be identified. There are so few cases of measles these days that if you describe a case in enough detail—age, sex, what country they traveled to, or where they are from—they can be identified.

While this dance protects people’s private medical information and avoids stigmatization, unfortunately, it leaves room for rumors to brew. Thankfully, we have historical data.

Bottom line

Contrary to rumors blaming measles on illegal immigration, historical data shows that measles is usually caught abroad by U.S. residents, who then bring it back home. The epidemiological reality is that we live in a globalized world, with more than 1 billion people traveling annually in and out of countries with disease outbreaks.

Last month CDC urged all travelers aged 6 months and older to get vaccinated, regardless of their destination. Note that this is earlier than “normal” (the first dose of MMR is recommended at 12-15 months), but it is needed given the number of cases we see globally, particularly during travel season. If my girls were still under one and we were traveling internationally, I would definitely take this extra precaution.

Love, YLE

*In the original post, I made a mistake. This was originally written as 98%, while index cases was 77%. This was fixed April 12, 2024.

In case you missed it:

“Your Local Epidemiologist (YLE)” is written by Dr. Katelyn Jetelina, M.P.H. Ph.D.—an epidemiologist, wife, and mom of two little girls. During the day, she is a senior scientific consultant to several organizations, including CDC. At night, she writes this newsletter. Her main goal is to “translate” the ever-evolving public health world so that people will be well-equipped to make evidence-based decisions. This newsletter is free, thanks to the generous support of fellow YLE community members. To support this effort, subscribe below:

So important to help stop the flow of anti-immigration propaganda re The Border w Mexico. Plus, I had no idea Mexico had a higher rate of vaccine protection than we have.

Thank you Katelyn Jetelina once again for your finely tuned professional information.

It’s so predictable and cynical that yet again immigrants are scapegoated for something negative.

Instead, immigrants to the US are just arriving later than the rest of us, who arrived later than the native peoples. We know how that went down, assuming we live in a state that still teaches history.

Selfishly we need the kind of labor and brains immigration brings, and without it our low birth rate will lead to economic contraction and recession.

Early in the coronavirus pandemic, of course people blamed immigrants, too. For example, looking back, a super spreader event with 1 million domestic travelers to New Orleans for Mardi Gras played a big role.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7872376/

Our problems are usually homegrown.