Why CDC health data are still reliable

...even amid challenges to communications and integrity

Back in February (a lifetime ago), when data were being edited under Executive Orders and all CDC communications were effectively frozen, I outlined four scenarios that would signal real cause for concern about CDC’s information. Two of them have now unfolded in the past month:

The breach of scientific integrity, for example, the autism and vaccines site along with other less publicized changes.

The injection of political messaging into HHS channels.

Never did I think I would see it, but here we are.

The full extent of the damage is still unclear, and how much more may occur remains unknown. But one question stands out: what is the integrity of the data itself? Public health data—the public information used to estimate disease, hospitalization, and death rates, for example—are a vital resource. Their value lies in their purity, reliability, accuracy, and accessibility.

Despite everything, I remain confident in CDC data. This largely stems from the U.S. public health system’s unconventional, decentralized structure. A pain in the butt fragmented system for epidemiologists, but one that now works to our advantage.

Hannah, the YLE Community Manager, pulled the top six questions you’ve been asking so we can provide answers. Here’s where things stand.

1. Why can we still trust CDC data?

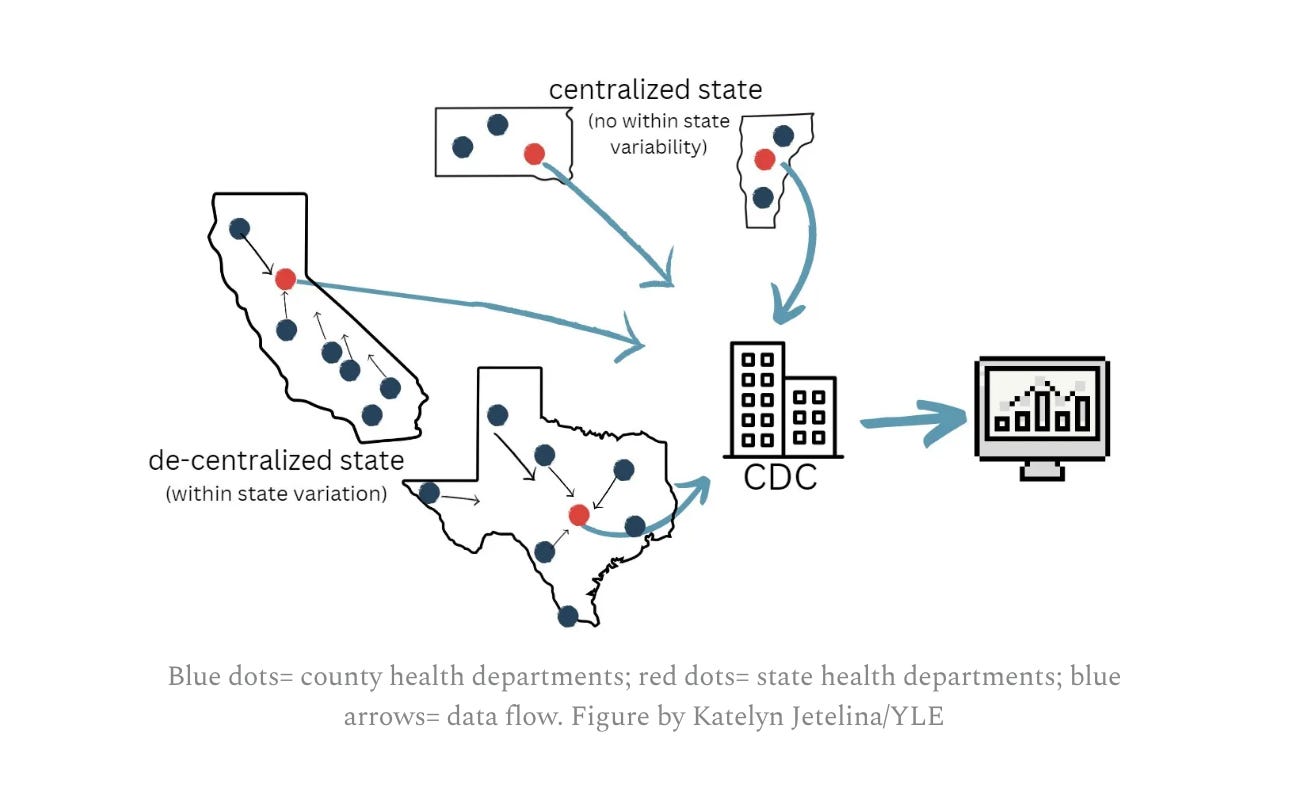

The key is a nuance most people find boring. Public health data in the U.S. do not flow from the top down; data are decentralized and built from the bottom up. Local and state health departments and hospital systems collect, manage, clean, and report data before they ever reach CDC.

Take flu data. When someone is hospitalized, the hospital records the case. That information moves to local or state health departments, where teams verify and clean it. Only then do states upload finalized numbers to CDC through secure systems. CDC then stitches these local puzzle pieces into a coherent national picture.

This role is essential because diseases do not respect state lines. CDC data inform cross-state responses, hospital capacity planning, testing needs, resource allocation, early warning signals, and shared lessons across jurisdictions. Without CDC, we would have 50 separate snapshots instead of a unified national system. Because CDC primarily stitches data rather than collects it, federal interference is much harder.

CDC does run direct data collection for vital statistics and surveys, including collecting information on vaccination uptake, mortality, and health behaviors such as smoking and nutrition. Most of these datasets remain intact, with exceptions: some data elements have been removed, like transgender status, and funding cuts may halt certain surveys.

2. What about states that may also want to interfere with data?

For many diseases, reporting is legally required by states. A classic example is measles: when a patient is diagnosed, the health care provider must report the case to the county or state health department.

But states voluntarily share this information with CDC.

If a state wants to stop reporting to CDC, for whatever reason and for whatever data, they have the authority to do so. We saw this challenge during COVID-19 when some states, like Texas, stopped reporting vaccination data after the emergency period ended. The result was a significant gap on the CDC dashboard, leaving an incomplete national picture.

This year, you could easily see a potential “flip” scenario: some states could choose to stop reporting to CDC because of a lack of trust in HHS.

3. Is automation helping detect outbreaks in this moment of strain? What about layoffs?

Yes! Automation is incredibly helpful for outbreaks, but humans do the work, too.

When someone is diagnosed with a foodborne illness, for example, the testing lab typically sends the bacterial isolate to the state public health lab. The samples are genetically sequenced, and results are uploaded to PulseNet, CDC’s database. Then, algorithms scan for genetic clusters on data from across the country. If a cluster is detected—which suggests infections are linked and may have been infected from the same source—an alert is issued to public health epidemiologists who begin investigating in partnership with environmental health specialists and food safety agencies.

This algorithmic step removes much of the guesswork from identifying the initial stages of foodborne illness clusters and is a mostly automated process. But the core of outbreak response still relies on human investigation—interviewing patients, tracing food histories, and linking cases to a source.

The more cuts we have to staff, the more limited our capacity will be to respond to some of these outbreaks. Many are bracing for next year, when budgets will be cut by billions.

4. Have data communications changed?

Collecting data is one thing. Communicating it is another. Communications capacity has been dramatically reduced.

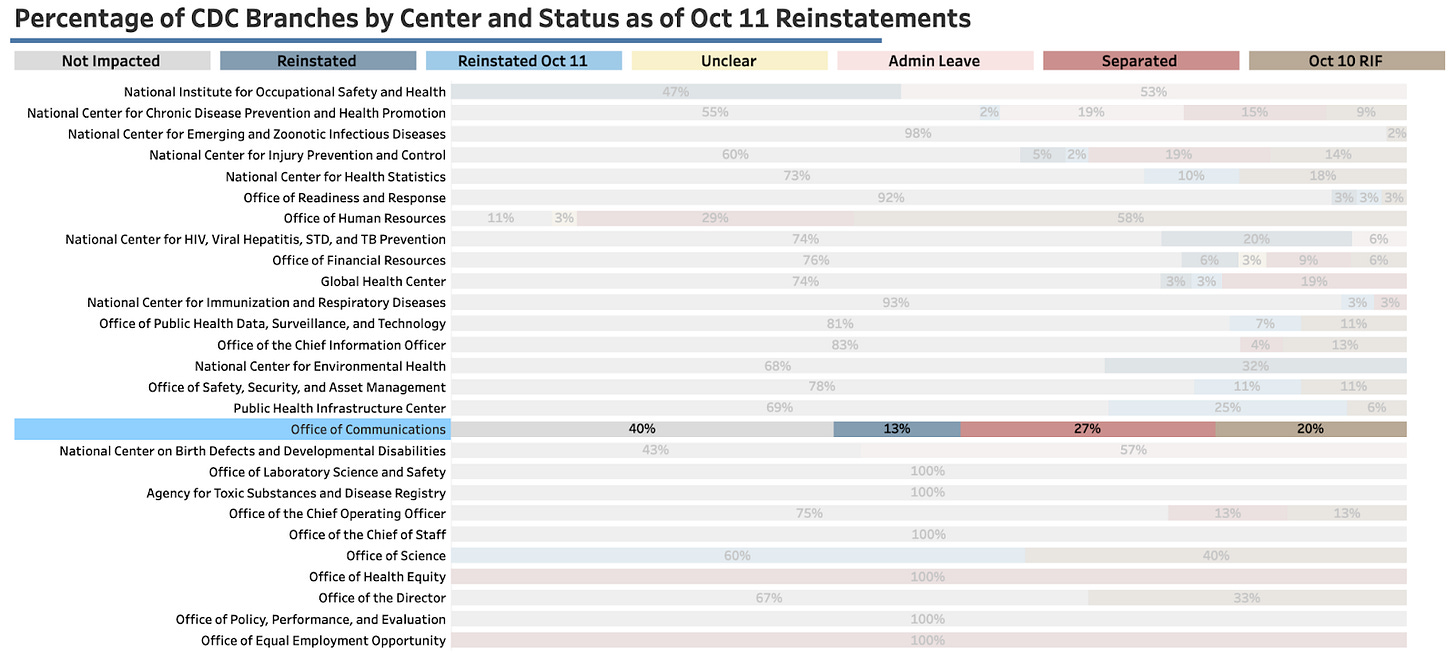

The National Public Health Coalition, a grassroots organization of fired HHS employees, found the Office of Communications is operating at roughly half of its pre-October capacity.

As you can imagine, this impacts outputs.

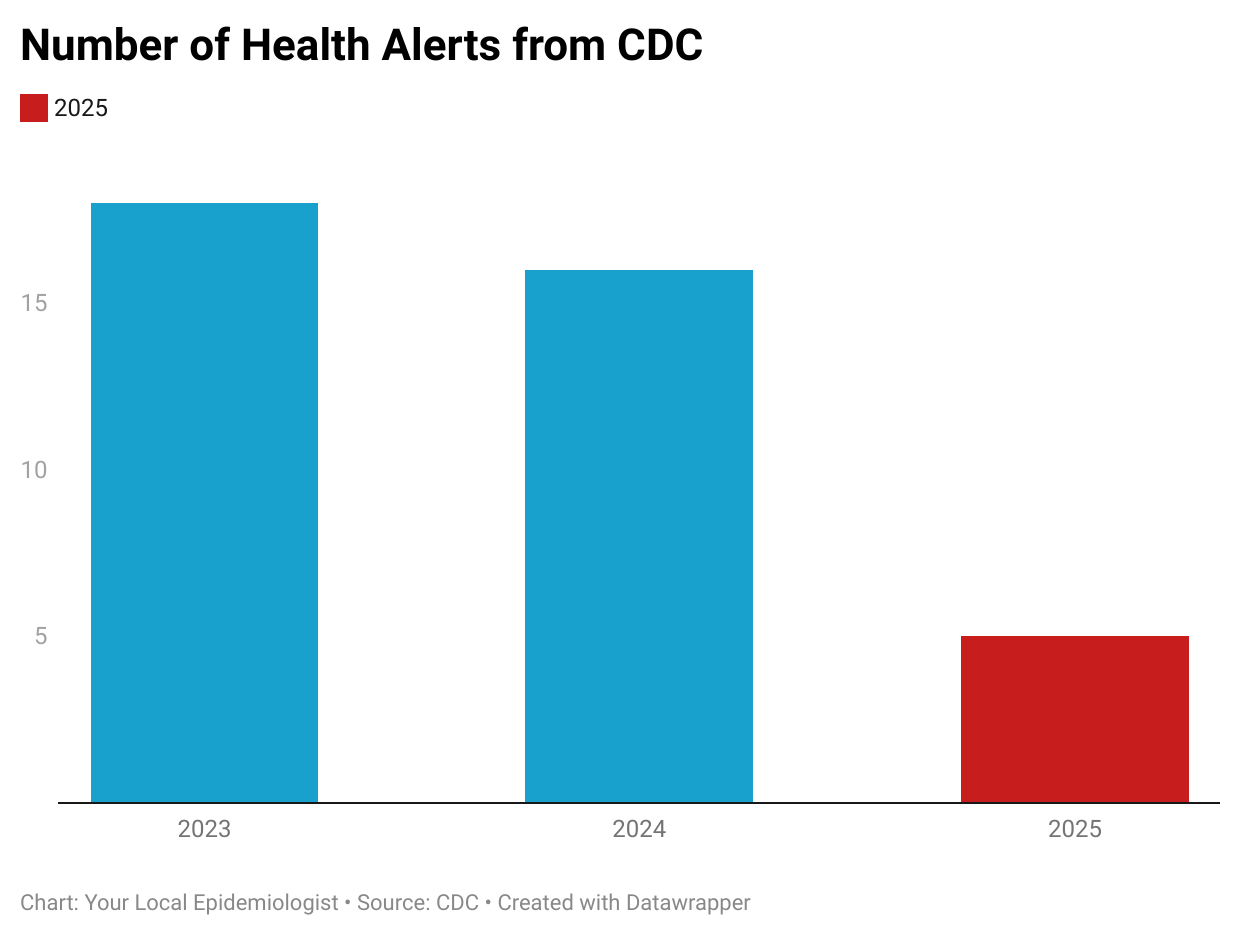

Take HAN—these are safety alerts sent to physicians as a heads up on what to look for when there’s an emerging issue. The HAN office still exists, but it takes significant initiative to complete a HAN, even when the administration cares about such matters.

HAN has published only five alerts since the new administration took office. For comparison, HAN published 16 alerts in 2024 and 18 in 2023.

5. Is there a world where a U.S.-based NGO gets created to effectively replace the CDC?

To some extent, this is already happening as quickly as possible. We see this from multiple angles:

Regional coalitions sharing communications, briefs, and insights

Non-federal groups synthesizing data, like the Vaccine Integrity Project

Communication efforts, including professional organizations like AAP (who has STEPPED UP on social media platforms), and grassroots efforts like The Evidence Collective

Data democratization efforts, like PopHIVE

The problem is that nothing can ever compete with the federal government’s budget, far-reaching infrastructure, and authority.

6. What does this mean for you?

You can feel confident that CDC data are accurately tracking diseases. And, if you’re data gurus like us, you can also feel confident using the CDC data. We will let you know when our confidence decreases.

But also keep in mind that other sources exist:

Local and state public health departments remain primary sources of data, often publishing their own dashboards.

Non-federal data sources such as WastewaterSCAN, Biobot, and PopHIVE provide additional datasets.

Bottom line

The data infrastructure is largely intact thanks to a decentralized system. As a nation, we will need to continuously ensure this is the case, as data are gold. The communications capacity, however, has been severely weakened.

Americans shouldn’t have to monitor inputs and outputs from the nation’s leading public health agency, but here we are.

Love, YLE

A special thanks to Katie Fullerton, a dear friend who spent years working in CDC data systems for a read through and feedback on this draft.

Your Local Epidemiologist (YLE) is founded and operated by Dr. Katelyn Jetelina, MPH PhD—an epidemiologist, wife, and mom of two little girls. YLE reaches over 320,000 people in over 132 countries with one goal: “Translate” the ever-evolving public health science so that people will be well-equipped to make evidence-based decisions. This newsletter is free to everyone, thanks to the generous support of fellow YLE community members. To support the effort, subscribe or upgrade below:

I'm grateful for the content that you all provide day in and day out. And, I'm also glad that you use "data" as the plural noun that it is! It's a welcome sign of respect for high standards of communication for which I'm grateful. Best wishes, ---tad.

Glad you recognize that the decentralized nature of US health data collection can be a feature, not a bug!

Vital statistics data -- birth and death certificates -- are also collected by the states, and not directly by CDC. This is why you go to an office of your state's health agency to get a birth or death certificate for various legal purposes. States do the primary cleaning and aggregation of the vital statistics data, consistent with national standards, and issue reports based on the data. As with nationally notifiable disease data, CDC collates the data from the staes to get a national picture. The process has been extensively automated in recent years, but still is a state-based endeavor.