Events like COVID-19 and mass shootings are hugely impactful to our society. Unfortunately, as time passes, we don’t do a great job at recalling events, integrating those events into our lives, or using those experiences to make future decisions/judgments.

Simply put, we forget.

Why and how

The mechanics of memories are relatively clear: a combination of neurons, a memory center in our brain, a process to consolidate memories during sleep, and a process to retrieve memories.

However, social psychologists have been grappling with a very different and challenging question for almost 100 years—not how we forget, but why.

The field has essentially settled on two overarching reasons:

Infodemic. We are simply inundated with too much information to retain it all. This information overload is at least partially responsible for our forgetfulness.

Biases. To wade through all of this information, we use shortcuts, or heuristics. These are mostly good and effective, but the human brain isn’t like a computer—it’s not just data in, data out. The way we think about things is not purely logical; biases and mental shortcuts have a large effect on memories.

Four biases influence memory

How we remember and make decisions is largely driven by our experiences. It makes it easier to remember certain things while forgetting others. There are many biases contributing to this, but four that are especially relevant:

Immune neglect. Just like our body’s physical immune system helps us stay healthy, we also have an emotional immune system that helps us be psychologically resilient. On balance, this is a good thing, allowing us to bounce back from difficult situations more quickly. The fear, outrage, or other negative emotions that big events arouse often don’t last that long, which impacts judgment and decision-making in the future.

Example: The motivation to make a change feels so strong in the immediate aftermath of a mass shooting, but is often shorter-lived than necessary to implement change. Most people get back to their lives as their emotional immune systems allow them to return to normal.

Availability (or recency) bias. When we make decisions, we don’t weigh the pros and cons equally; some things count more than others for individuals. Things that readily come to mind will sway us more, regardless of their actual importance or value, than those that are harder to recall.

Example: The early days of lockdowns, sanitizing groceries, and masking are, for many people, in the past. This makes the details of those bygone times difficult to recall and causes more recent, less frantic memories to impact our decisions.

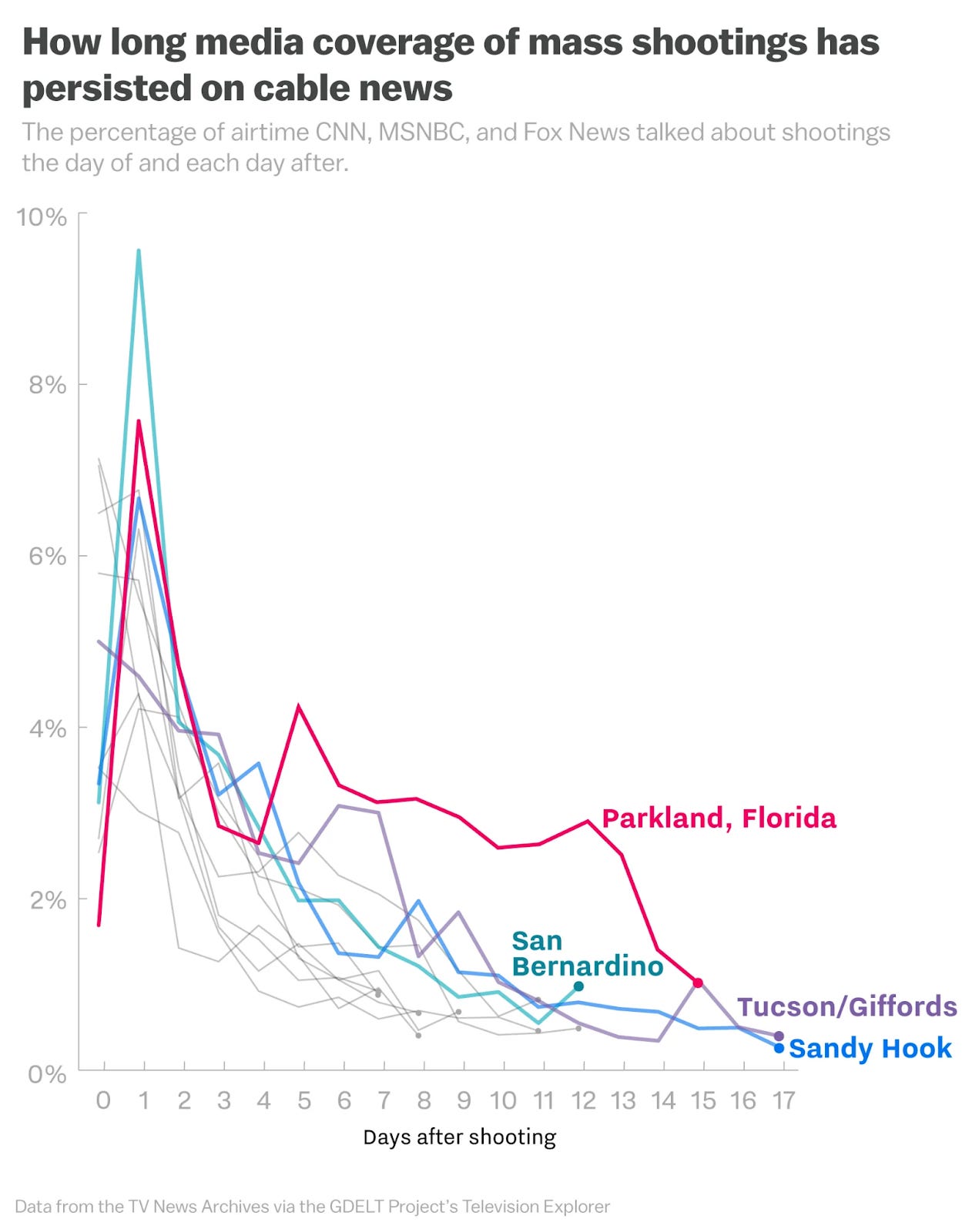

Example: News coverage is a two-way street. As time from an event increases, people are less likely to click on articles about it, and articles are therefore less likely to cover these topics. The media coverage of mass shootings significantly declines over time. This makes it easier to forget for those outside of the directly impacted community.

Figure from Vox. Source Here.

Hindsight bias. “I knew it all along!” Humans tend to overestimate their ability to predict what, in reality, was an unpredictable event. This can negatively affect our memory and decision-making in the future.

Example: “We shoulda known _____!” This will negatively contribute to decisions about preparing for the future of COVID—or even the possibility of the next pandemic. Overconfidence can be detrimental, as some will feel like they will be able to predict or foresee the next big thing.

Cognitive dissonance. Early 2020 was horrible, and things are much better now . . . but not all the way better. This reconsideration of a past big event—that sucked, but now things are good—can feel off-putting or inconsistent. Wanting to resolve that inconsistency, people may discount how bad things were then, instead focusing on how good they are now.

Example: Each time a mass shooting occurs, millions of people could have the same reaction: wow, that’s horrifying, but I wasn’t personally affected. This inconsistency of thought feels uncomfortable, as we might think we should be feeling 100% bad. To make ourselves feel better, we might convince ourselves that, actually, the shooting wasn’t so bad; these cognitive gymnastics could hinder large-scale responses like long-term government action.

What we can do about it

Although these biases are generally unavoidable, the news isn’t all bad. Studies show that we are particularly prone to using these shortcuts in certain situations, like when we are tired, hungry, or stressed out. Addressing these, before or during decision-making, can help.

What’s more, research indicates that simple awareness of the biases can reduce their influence on us. In other words, we can help short-circuit them by simply shining light.

Bottom line

Memories of the same event do not look the same for everyone. Sometimes the event doesn’t even become a memory at all. Humans have evolved to use mental shortcuts to more smoothly navigate the world.

Unfortunately, this typically means normalizing events—like a pandemic or mass shootings—which will ultimately hurt us in the end, leading to a lack of pandemic preparedness or insufficient pushes for gun reform. This can lead us into the never-ending cycle of panic and neglect unless we actively fight against it.

Love, YLE and BR

Dr. Ben Rosenberg is an assistant professor of psychology at Dominican University of California and director of the Health and Motivation Lab.

“Your Local Epidemiologist (YLE)” is written by Dr. Katelyn Jetelina, MPH PhD—an epidemiologist, data scientist, wife, and mom of two little girls. During the day she works at a nonpartisan health policy think tank and is a senior scientific consultant to a number of organizations, including the CDC. At night she writes this newsletter. Her main goal is to “translate” the ever-evolving public health science so that people will be well equipped to make evidence-based decisions. This newsletter is free thanks to the generous support of fellow YLE community members. To support this effort, subscribe below:

OH! And by the way: this is why we depend on reliable governmental institutions and honest officials dedicated to common welfare, civic responsibility, social infrastructure and the greater good.

As a college student history major in the 1970’s I took a class in the History of Disease which focused mostly on social history. There were many interesting things ( how Polio led to the growth of overnight camps in some areas….who knew?) but the most fascinating thing was how people quickly “forgot” about the influenza epidemic in the earlier part of the century. How very little it was discussed after. I thought Downton Abbey did a good job of portraying this. Your home was turned into a hospital??….barely mentioned after. I have always expected COVID to be similar.