Why is trust in vaccines declining?

A look back at the pandemic, what was said, and where communication broke down.

A note from Katelyn: YLE will do something a little different for a few posts. We’ve created a mini-series with a look back on the Covid-19 vaccines during the pandemic: what was said, what actually happened, and where communication broke down. This is a huge part of why we are seeing a decline in trust in other vaccines (and public health altogether) now. This will be hard to read, but it is a much-needed attempt to clean the wound so it can heal. I’m handing the mic over to Kristen P.—there is no one better to handle the delicate dance on this tough topic.

This is post 1 of 4 aimed at holding up a mirror to Covid-19 vaccine communication to identify lessons learned. We must do better next time.

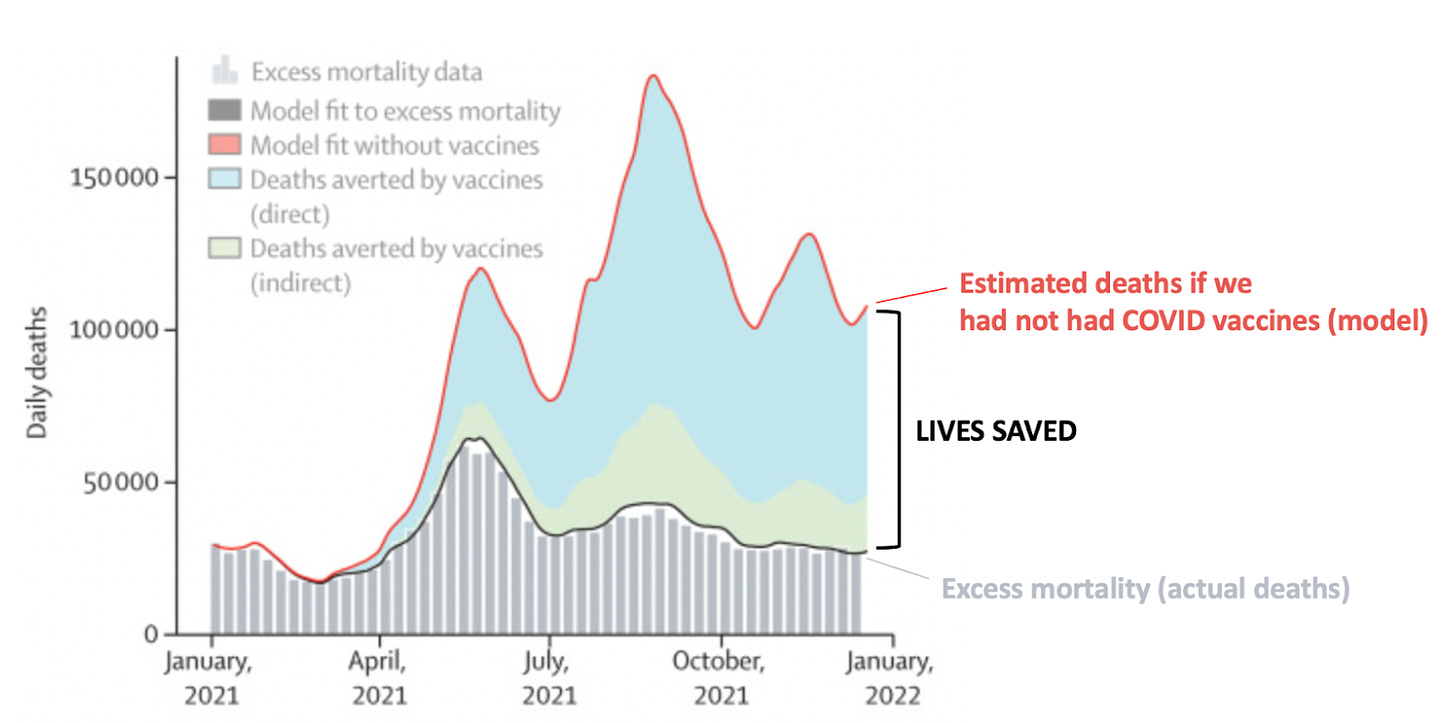

The Covid-19 vaccines are undoubtedly among the most impressive medical feats in history. One model estimated that Covid-19 vaccines prevented 20 million deaths worldwide in their first year alone. As a physician-scientist, watching the scientific world come together to produce not one but multiple vaccines in a matter of months in the midst of a global pandemic has been truly awe-inspiring.

But that is not how many people remember them.

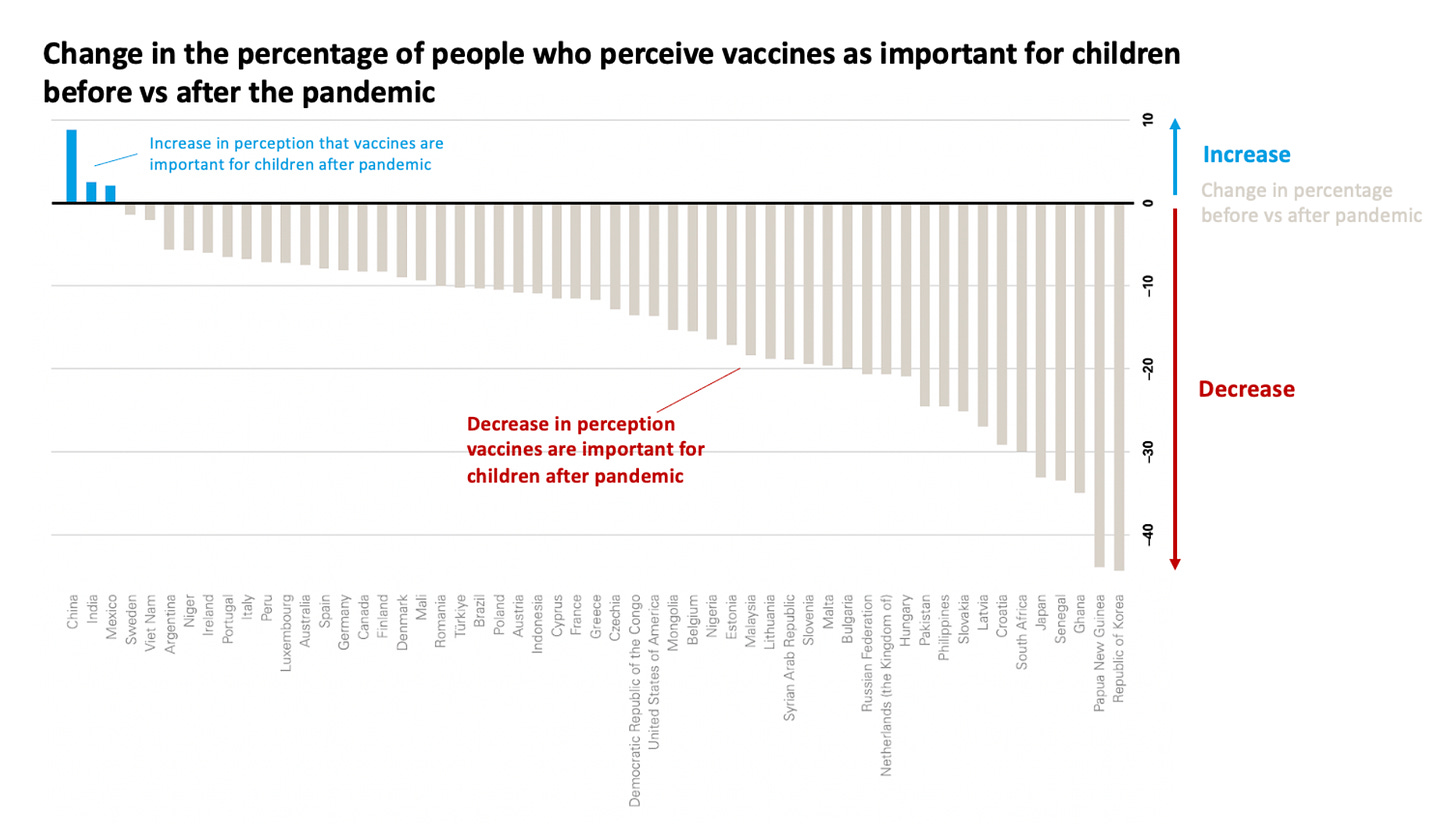

Despite developing multiple effective vaccines that saved millions of lives during a global pandemic, trust in vaccines, even beyond Covid-19 vaccines (like routine childhood vaccinations) got worse, not better.

Misinformation played a huge role, but it was not the only problem

It’s easy to blame it all on misinformation and disinformation, which undoubtedly played a role. The list of rumors about the Covid-19 vaccines is certainly impressive—every week, there was a new alleged “ingredient” that was somehow toxic, and the level of creativity that inspired the various false rumors would be laudable if it weren’t so dangerous.

I’ve spent hundreds of hours debunking various Covid-19 vaccines rumors and don’t want to minimize the impact these rumors had on sowing distrust in vaccines.

But that’s not what this series is about.

Misinformation, or miscommunication?

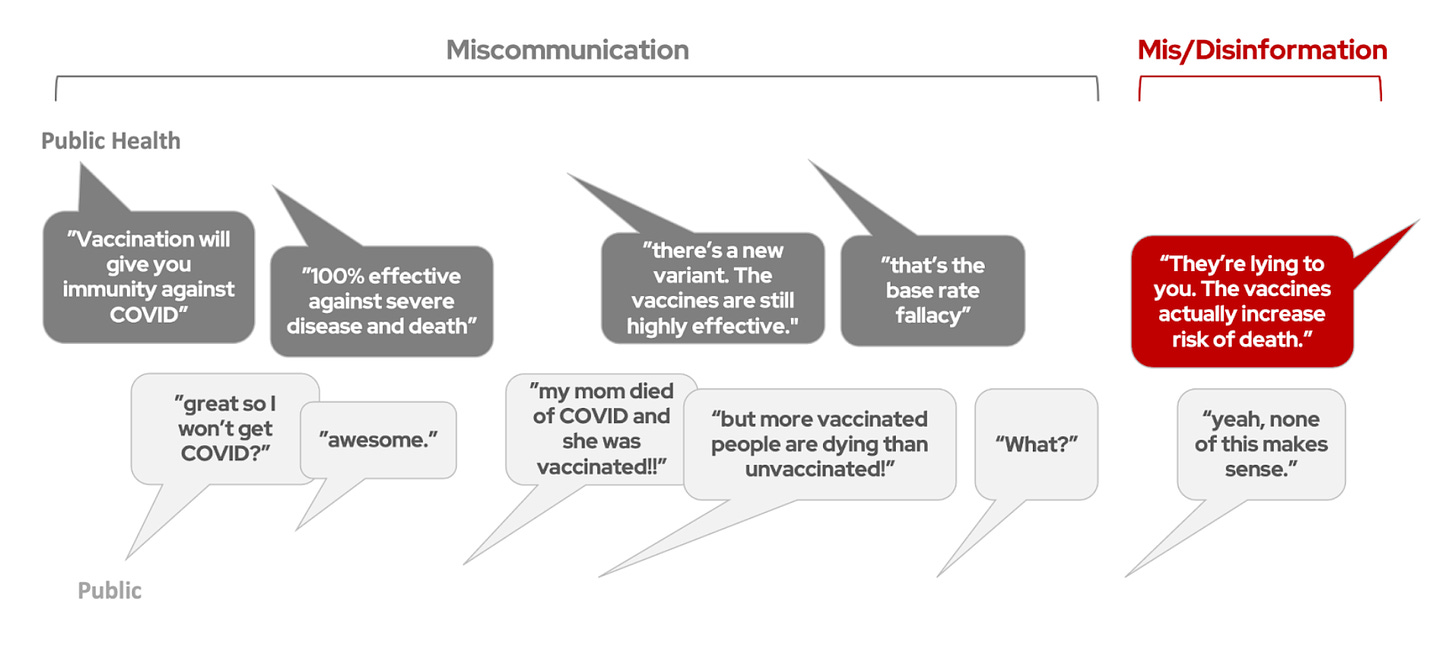

A lot of “misinformation” that was circulating could more aptly be described as “miscommunication”—public health officials saying one thing and the public hearing something entirely different.

I thought Covid-19 vaccines gave us immunity like our childhood vaccines do—why are vaccinated people getting sick?

I thought you said all the vaccines give us 100% protection against severe disease and death—why are most Covid-19 deaths now among vaccinated people?

If the vaccines prevent infection, why do vaccinated people still need to wear masks?

If I was okay after a Covid-19 infection, am I okay getting measles and other diseases then, too? Are we overreacting?

These are all valid questions that deserve explanations. The answers provided were often confusing, constantly changing, or fell short, leaving the (false) impression in many people’s minds that Covid-19 vaccines don’t actually work, and that the scientific community was pushing a failed vaccine, calling other vaccines into question as well.

Poor communication is a gateway to misinformation

When valid questions aren’t answered adequately or from a place of empathy, it’s not unreasonable that trust declines. And when trust starts declining, people may be more open to believing rumors they hear. Plain old miscommunication can set people on a path to believing misinformation and disinformation.

Misinformation is not going away, and we can (and will) keep addressing rumors as they come. But the generation of these rumors is, for most of us, completely out of our control. In the public health and medicine field, we should be far more interested in looking at what is within our control: our communication, and how we can do better.

The first step is figuring out what went wrong. In this series of posts, we will look back at the story of the Covid-19 vaccines and the communication problems around them. Some pandemic communication blunders were obvious (flip flopping on masks, for example), but others got less attention, and were only obvious to those who were disappointed and confused. The goal is not to point fingers or assign blame—it was h.a.r.d. to communicate to a polarized nation during a deadly pandemic when yesterday’s data was already outdated. But we need to get a view from outside our bubble and understand how messages were perceived, so we don’t miscommunicate next time.

Bottom line

Miscommunication during a public health emergency can inadvertently destroy trust. Now, with the advantage of hindsight, we need to look back and see what went wrong so we can do better today.

Up next in this mini-series: Expectation management. See you Thursday.

Sincerely, KP

Kristen Panthagani, MD, PhD, is a resident physician and Yale Emergency Scholar, completing a combined Emergency Medicine residency and research fellowship focusing on health literacy and communication. In her free time, she is the creator of the medical blog You Can Know Things and author of YLE’s section on Health (Mis)communication. You can find her on Threads, Instagram, or subscribe to her website here. Views expressed belong to KP, not her employer.

“Your Local Epidemiologist (YLE)” is a newsletter with one purpose: to “translate” the ever-evolving public health science so that people will be well-equipped to make evidence-based decisions. This newsletter is free to everyone, thanks to the generous support of fellow YLE community members. To support this effort, subscribe below:

This will be a very interesting series to read. In addition to mea culpas, some of which are due, we should also forgive much of the “flip flopping” that occurred in real time as we learned about the durability of vaccine effectiveness for example. Or that was compelled by political pressure and intimidation like defining a public health tool (the mask) as an emblem of tribal identification, and then heaping scorn. It’s always easy to look back and second guess.

I also hope we don’t fail to acknowledge a very committed and hostile anti-vax community that now has one of its major proponents campaigning for the Republican presidential nominee with the hopes he can take the reigns of Health and Human Services. No amount of introspection and analysis about health communication will be sufficient to overcome that rigid and warped mentality and agenda.

Just look at the literal death threats that Dr. Jetelina received. I get a taste of that sometimes when I post stuff, like a recent article I did on why we choose to keep our daughter up to date with Covid vaccines. You get this:

“This piece of sh*t psycho is a f*cking murderer. F*cking moronic.” ~Derek Krane

“This so-called “doctor” is a brainwashed fool, and is part of the genocide agenda. He is complicit in murder." ~David Geezermann (an alias I presume)

“...the example of a mercenary and accomplice to genocide, who deserves to be in lifetime prison. The reason he is still working to murder children proves once again that we are in a depopulation war.” ~Professor Fred Nazar

“Some people should not be allowed children.” ~Tim West

“…has the CDC far up his *sshole. He suggested you murder your child with the Covid vaccine. I agree with you, Ryan. It’s not malpractice. It’s murder.” ~ Tim Holt

Sound familiar? I have a post half written about how to deal with conspiracy theories and theorists, let me know if you want a first look or post here!

And thank you for the bravery of the public health community alongside the healthcare workers like myself during the darkest days of this pandemic. Nothing brought more light, hope, and improvement to this situation than vaccines.

About masks, not vaccines: I believe that public health officials lost sight of probably the most important reason for me to wear a mask, and properly: to protect others from me. It’s not the nanny state telling me what I should do to protect myself — it’s the community’s interest in reducing transmission from people who are infectious without major symptoms (like before they get sick)….. in December 2021, in London, I saw posters from the NHS that had a drawing of a person wearing a mask, with the words “I wear this to protect you. Please wear yours to protect me.” I rarely saw this message so clearly articulated.