In my prior life, I was an assistant professor at the University of Texas, leading a research lab focused on a single mission: breaking the cycle of violence using infectious disease modeling. This sounds technical and high-level, and if you looked at any of my 100 publications, they would be barely understandable to the populations they served.

In reality, it wasn’t theoretical. I partnered directly with survivors of child abuse, sex trafficking, and domestic violence. We collaborated with police officers who witness trauma daily. And, together, we built solutions: a new police dispatch system, domestic violence screening integrated into medical records, and better EMT training to detect elder abuse. These efforts had a real-world impact. Police suicides declined. More patients are connected to victim services. More seniors were protected.

All of this work was funded by the National Institutes of Health (NIH).

This week NIH is facing a major funding shift that could reshape the future of research in the U.S. The fallout has been swift. While 22 states have filed a legal challenge, universities in other states are either halting research or continuing with immense uncertainty.

The biggest challenge in all of it, though, is that people don’t know what NIH does or how its funding positively impacts their lives. If the public doesn’t understand, feel, or recognize it, how can we expect them to defend it?

Center of the changes: indirect costs

The latest debacle centers on “indirect costs.” For every NIH grant awarded for research, funding is divided into two categories:

Direct costs cover the actual research—salaries, fieldwork expenses, stipends for study participants, etc.

Indirect costs cover the infrastructure that makes the research possible—rent, electricity, internet, security, compliance, human ethics review, administrative support, and even toilet paper in buildings.

At my university, the indirect cost rate was 56%. That meant if I received a $100,000 grant, the university would receive an additional $56,000 to cover research infrastructure. So, a total of $156,000 would come through the door from NIH.

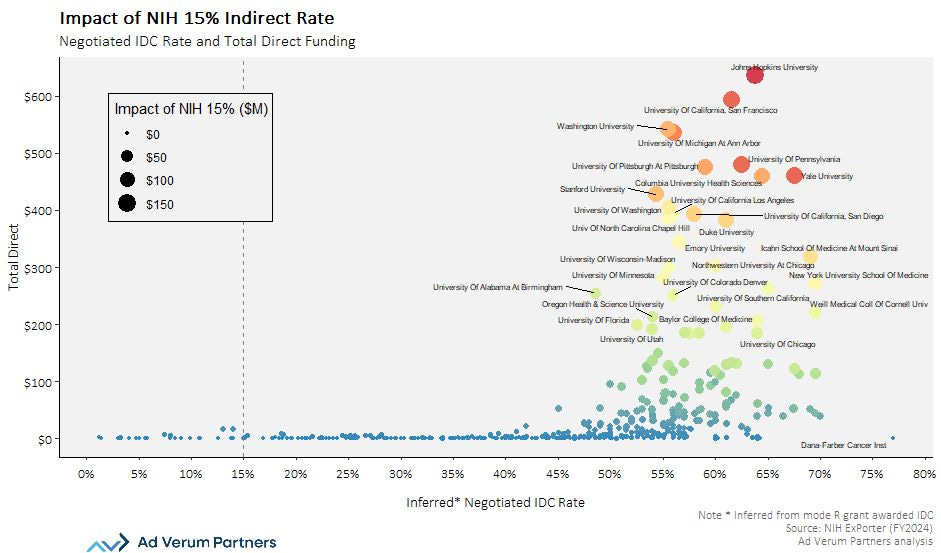

Indirect costs are specific to each institution, so they vary. In some cases, the percentage is as low as 10%, but in some, it is upwards of 80%. They often reflect the location of the institution and the service provided to the researchers. For example, in the graph below, New York University is higher than the University of Wisconsin, in part because of rent. The rates are negotiated with NIH every few years.

The new administration has slashed “indirect costs” from research grants to 15%, down from a previous range of 30-80%, to slim down government spending. In my $100,000 example, cutting the indirect rate to 15% would mean $15,000 for the infrastructure to do my research, leaving a $41,000 shortfall. This could mean no internet for my computer to analyze police officer surveys or no internal team ensuring that all my research was up to ethical and human standards.

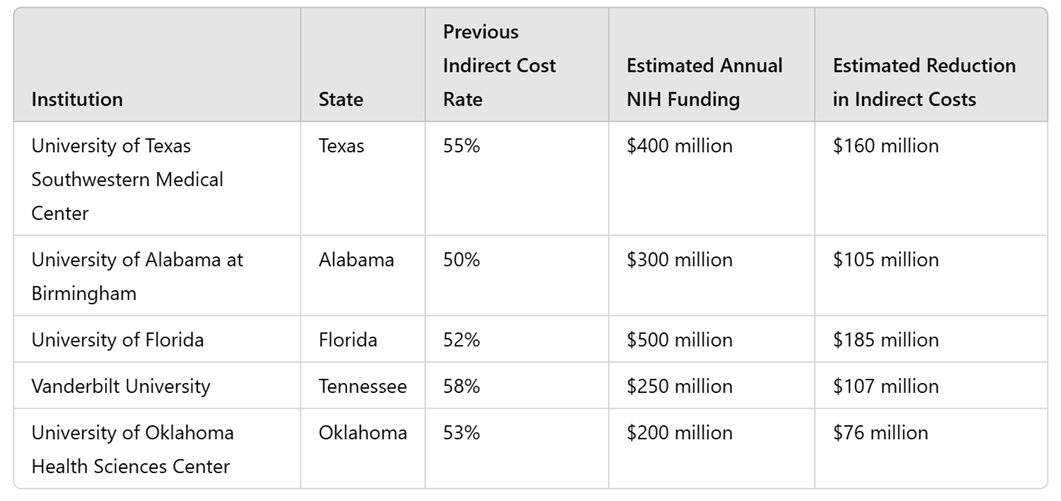

This deficit adds up fast grant after grant. Universities will lose hundreds of millions in funding, regardless of whether they are in a red or blue state.

Universities will somehow have to compensate for these losses. That could mean:

Hiring freezes and layoffs (fewer faculty, larger class sizes)

Limiting research volume (accepting fewer grants, reducing innovation)

Higher tuition and reduced financial aid

Cutting ethics and compliance oversight (fewer safeguards for research integrity)

Eliminating non-grant-funded academic programs

Private universities, like Harvard, may have endowments to cushion the blow. Public universities do not. Many already operate on razor-thin budgets and will be hardest hit.

Why should you care?

Americans have little empathy for institutions, and I would argue, rightfully so. Ivory towers often come off as sterile robots—disconnected and paternalistic. Even with this news, headlines and talking points on social media are high-level.

However, academic institutions are a part of your community. In some states, like Alabama, universities are the largest employers. Nationally, this sudden indirect rate cut puts 400,000 jobs at risk and threatens $80 billion in economic benefits—not to mention the economic benefit of progress in cancer, diabetes, heart disease, mental health, and services for victims of violence, for example.

Okay, what is the solution?

It’s not surprising that the public has questions about indirect costs—even researchers are often frustrated by them:

Where does this money go?

Why do some universities charge more than others?

Could institutions allocate funds in ways that benefit research more?

I don’t oppose a legitimate audit of federal functions to determine where we are overweight. Reimagining the health agencies is a useful and healthy process. Changes must be made at NIH and universities in the short term. For example, I have often thought our indirects were inflated, but without financial transparency, it’s impossible to know.

But a rushed, two-day policy change is just reckless. Destruction seems to be the goal rather than a healthy, helpful scalpel. And it certainly feels targeted, as it’s unclear how a $4 billion cut will make a big impact on a $1 trillion goal of cutting government spending, especially when the proposed cut has a direct return on investment ($2.46 of economic activity for every $1 in NIH funded research).

The scientific community has to get much better and smarter at communicating with the public.

Regardless, from the undercurrent of conversation on indirect costs, it’s clear that researchers can no longer afford to remain silent. Scientists and institutions have relied on papers locked behind paywalls, buried in jargon, and detached from real-world storytelling. Their work has remained invisible to most Americans, and this strategy has failed. We cannot wait for a crisis to explain why research funding matters. Community engagement has to be a central core of research.

As a professor, I would assemble infographics and send them to the participants, like police officers, to show that their insights were valued and drove tangible change. But this was done in my free time. When I was getting ready to go up for tenure, YLE— which would get more than 1 million reads compared to my scientific articles that got 10—was represented as one buried bullet under community service. I never took one hour of class that taught the value of stakeholder engagement, scientific communication, or science translation. And many, many colleagues often question why I write YLE or why scientific translation is needed in the first place.

All of this has to change. Through institutional incentives and support, and culture change.

Bottom line

I’m not surprised that people have legitimate questions about the institutions that are supposed to serve them. I, too, have questions. Reimagining the health agencies is a useful and healthy process. But this change with a 48-hour deadline is a punch to the jugular.

Research (including the fine print of indirect costs) isn’t abstract—it shapes our communities’ economies, our families’ health, and the future of innovation.

Love, YLE

Your Local Epidemiologist (YLE) is founded and operated by Dr. Katelyn Jetelina, MPH PhD—an epidemiologist, wife, and mom of two little girls. Dr. Jetelina is also a senior scientific consultant to a number of organizations, including CDC. YLE reaches over 320,000 people in over 132 countries with one goal: “Translate” the ever-evolving public health science so that people will be well-equipped to make evidence-based decisions. This newsletter is free to everyone, thanks to the generous support of fellow YLE community members. To support the effort, subscribe or upgrade below:

Things are in the works for a 50-state march for science to be held in state capitols on March 7.

Thank you. Please tell us how we can help with all these slash and burn policies the new administration is authorizing? Are there steps we can take to fight these cuts? (I'm trying to be polite; I want to scream and swear at the current leaders.)