I’m briefly coming out from hiding (a.k.a. summer break) to bring you a Covid-19 update. It seems like everyone has it right now (including the President). And I’m getting a ton of questions!

Let’s jump in.

We are in the middle of an infection wave.

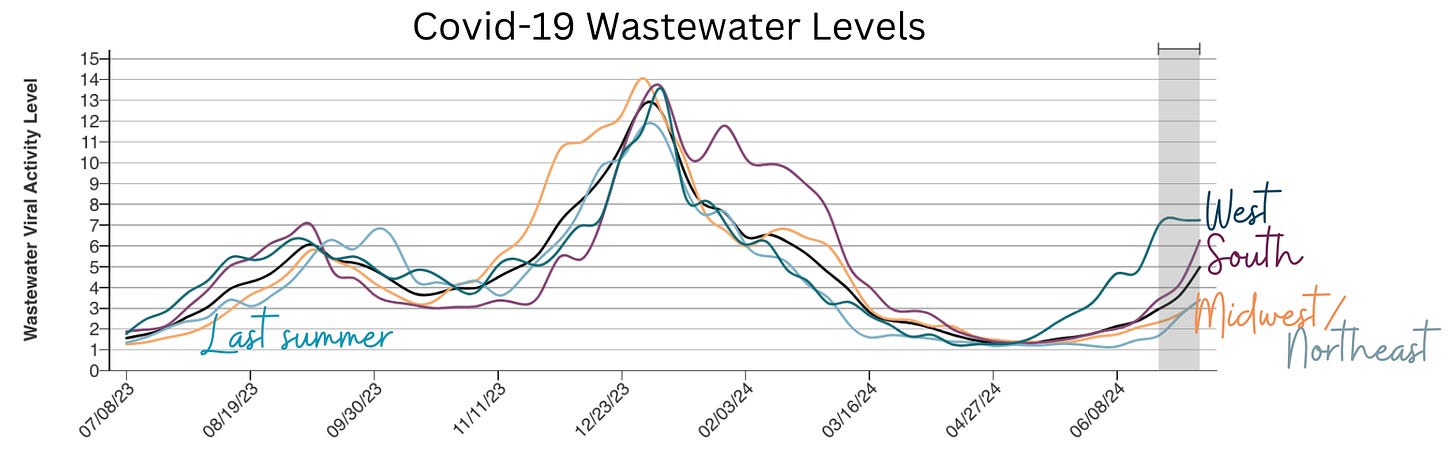

Covid-19 levels in wastewater—one of the best (only?) metrics of community spread these days—have reached the “high” category. This means that if you’re sick today, it’s likely Covid-19. This also means it’s time to get that indoor air moving and to wear a mask if you don’t want to get sick.

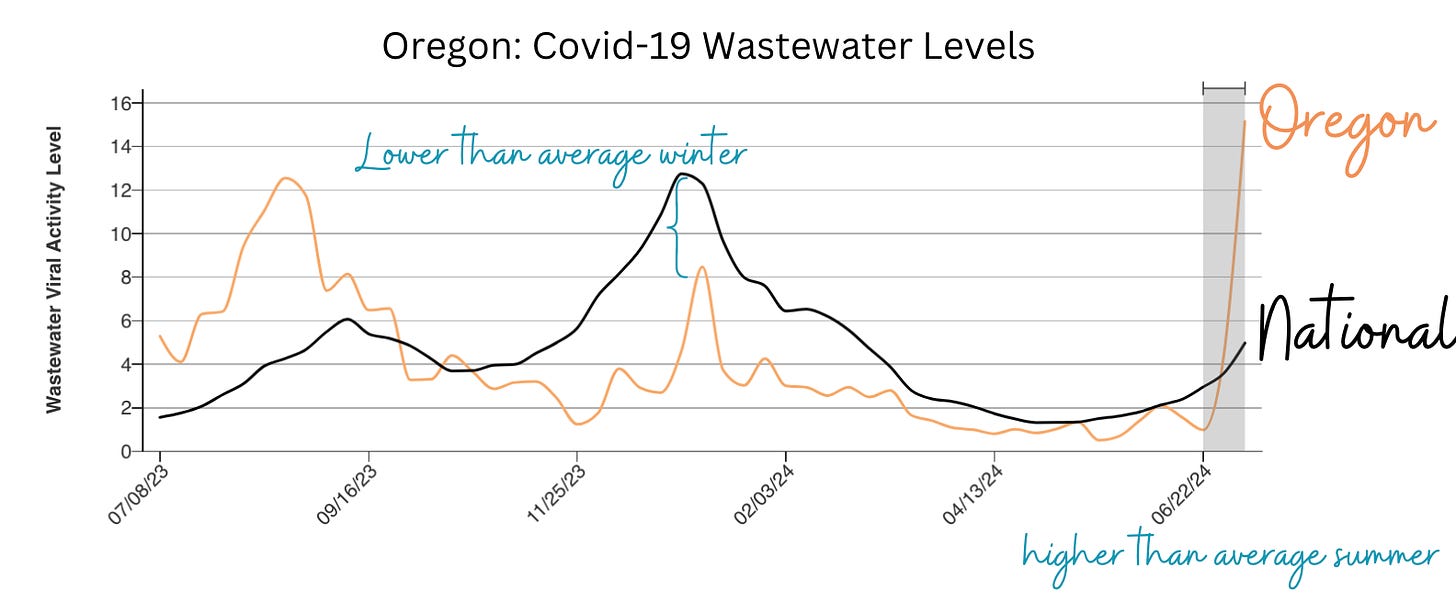

The West is leading the way with infections, and levels are higher than last summer’s peak. It’s hard to tell if the West is peaking. While Hawaii has already peaked after its huge infection wave, California and Oregon continue to increase considerably.

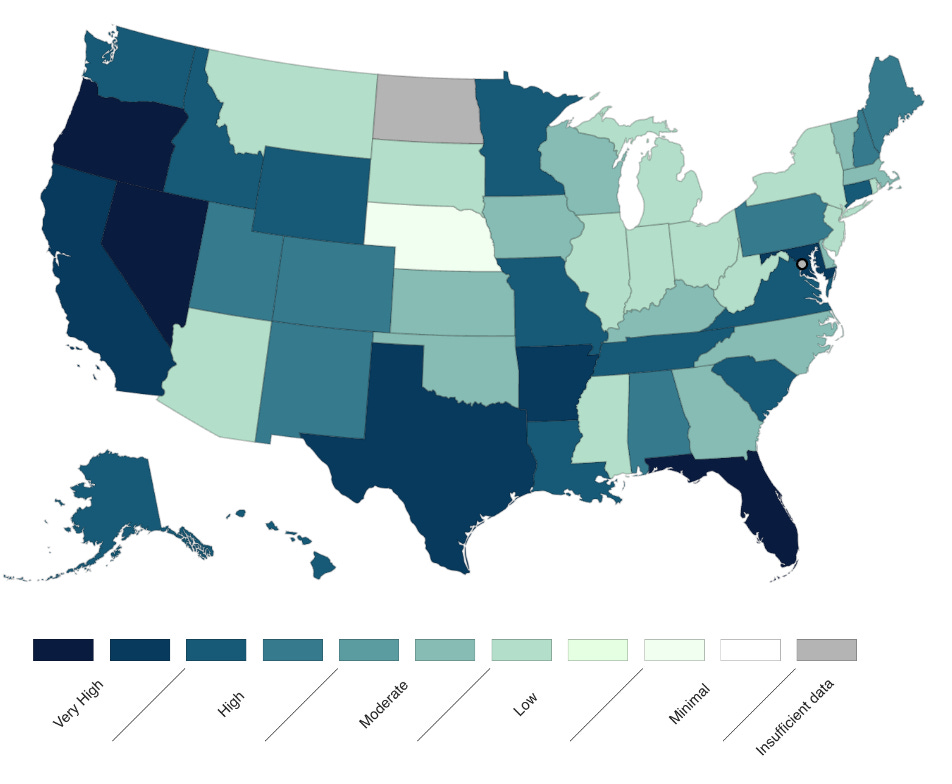

Other regions are following suit. In fact, 26 states have “high” or “very high” levels of Covid-19. (Enter your state here to see local levels.)

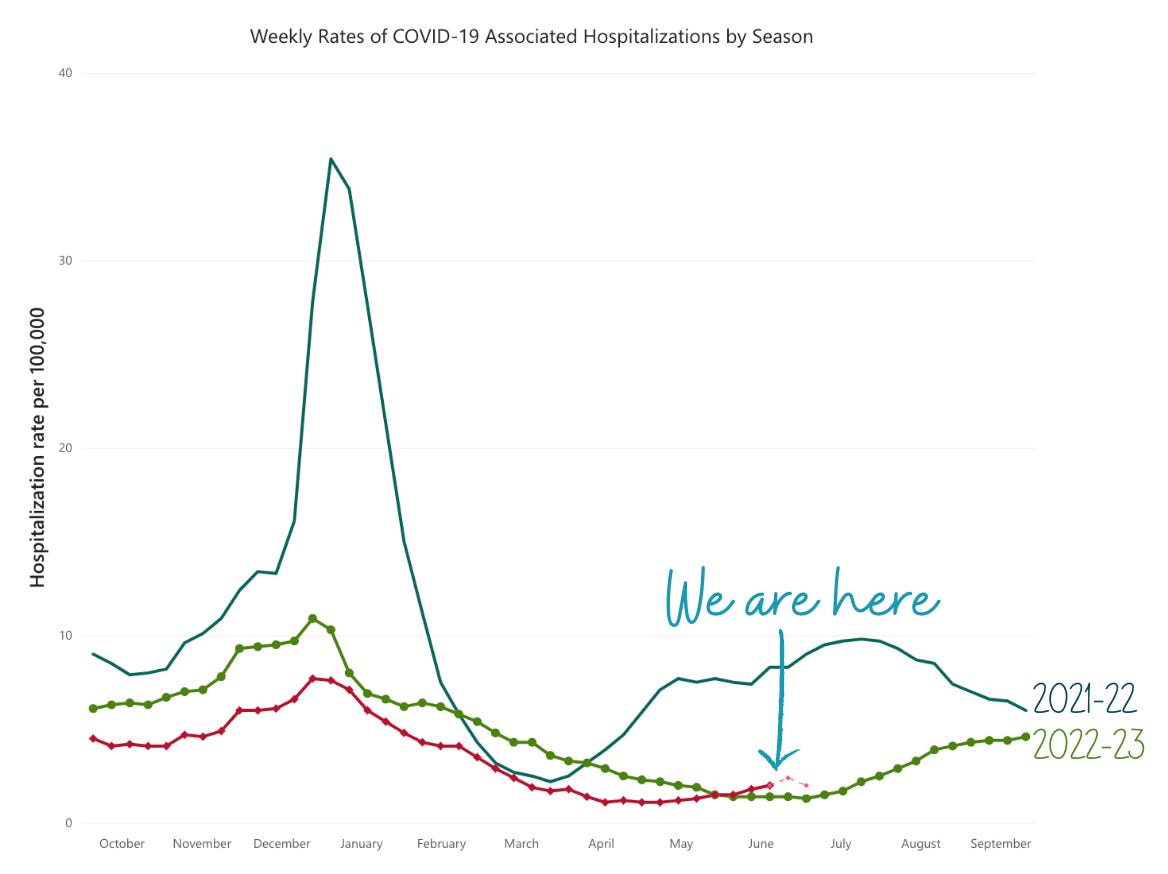

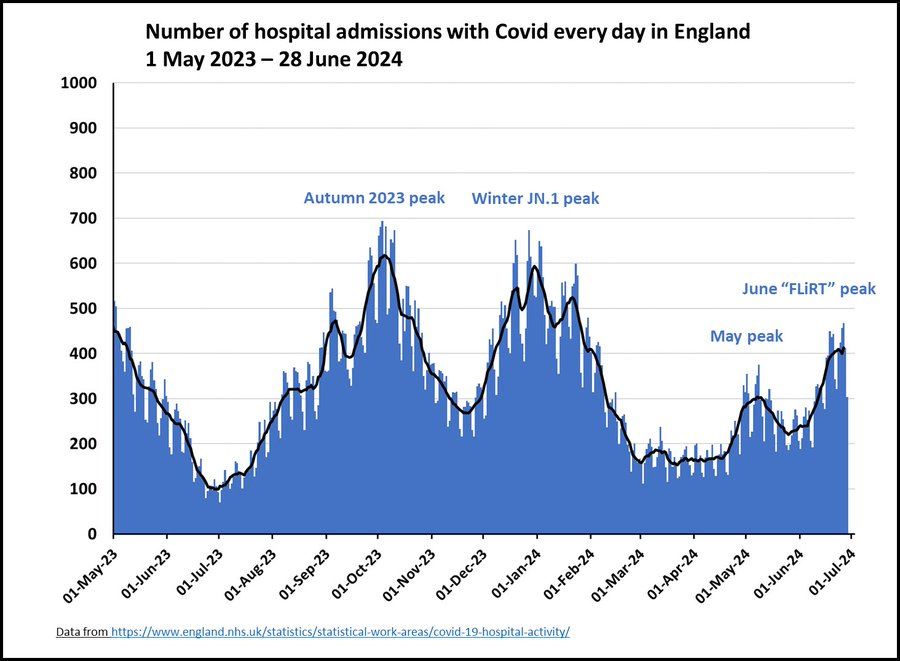

Severe disease is also increasing, but starting at low levels. Thanks to population immunity building, rates are not as high as last summer’s peak (or the summer before). (Note for those data gurus: The figure below is among a subset of hospitals that have consistently reported data over time. In other words, the lower hospitalization rate isn’t due to a change in reporting behaviors.)

In the UK, which always seems slightly ahead of the U.S. in waves, hospitalizations have peaked and remained lower than in Winter.

We’ve had a wave each summer. Why?

This is due to the combination of three things:

Behavior change. People move inside due to the heat, and most spread happens indoors.

Covid-19 keeps mutating quickly—about twice as much as flu. The latest variant, KP.3, specifically its descendant KP.3.1.1, is a little booger because it dropped a mutation on the spike protein, which seems to be effective in getting past our first immunity wall (called neutralizing antibodies.)

Waning immunity. ~20-30% of the U.S. population was infected with Covid-19 this past winter, which means the virus has plenty of pathways to find due to low immunity. Among states with mild Covid-19 winters, like Hawaii and Oregon, summer waves are very high.

I am surprised by how early this summer wave is (typically, we see it later in the summer) and how high infections are getting. I hoped we would see smaller and smaller summer infection waves each year. Alas, Covid-19 has different plans.

Should older people get the vaccine now or wait for fall?

We are seeing uncomfortable mortality rates among medically vulnerable people, like older adults in nursing homes, who are more than 6 months out from their last vaccine. For older adults who didn’t get their vaccine this spring, I suggest getting a vaccine now. But do it soon, as we want at least four months between this and the upcoming fall dose, so that it works best. Last year, the winter Covid-19 wave started in November.

How do I read the latest CDC guidance?

This is the first wave since the updated CDC Covid-19 guidance. As a reminder, if you get infected, CDC recommends approaching isolation in two phases:

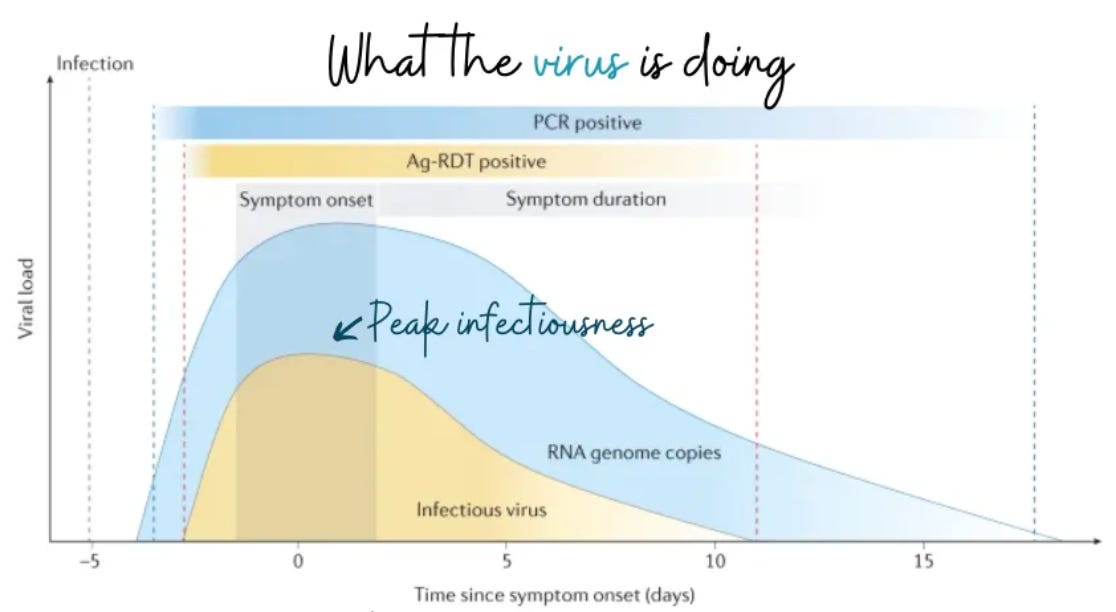

Phase 1: Stay home when sick until your fever resolves for 24 hours or your symptoms improve. But many people remain contagious beyond this timeframe, though, so…

Phase 2: Use caution for five days by taking additional precautions (e.g., wear a mask; or test before seeing grandma at the nursing home).

But what is the best approach? Isolate until your at-home Covid-19 test turns negative, which could be anywhere between 3 and 15 days. Once it turns negative, you can be confident you’re no longer infectious. Unfortunately, many people cannot afford tests or to miss work for this long. If you leave isolation beforehand, please wear an N95.

Is anything new happening with Paxlovid?

Evidence shows that Paxlovid works for a small subgroup of people: medically vulnerable over 65 years and those who are not up-to-date on Covid-19 vaccines.

Unfortunately, Paxlovid is not as effective as we had hoped for everyone else. Evidence suggests that it doesn’t protect against long Covid, and it doesn’t decrease the number of days you’re sick (if you’re up-to-date on vaccines).

What about airplanes?

A lot of people are traveling this summer. Remember that the virus likes crowded, indoor areas with poor circulation, like airport terminals and planes before takeoff. Longer flights also pose more risk—for every 1-hour increase in flight duration, there is an additional 53% risk of infection.

Bottom line

Covid-19 continues to do its thing. We are in the middle of an infection wave, and hopefully, it won’t find you, so you can continue to enjoy your summer. Given these news cycles, we could all certainly use a break.

Love, YLE

“Your Local Epidemiologist (YLE)” is written by Dr. Katelyn Jetelina, MPH PhD—an epidemiologist, wife, and mom of two little girls. During the day, she is a senior scientific consultant to a number of organizations, including CDC. At night, she writes this newsletter. Her main goal is to “translate” the ever-evolving public health science so that people will be well-equipped to make evidence-based decisions. This newsletter is free, thanks to the generous support of fellow YLE community members. To support this effort, subscribe below:

Appreciate so much that you took time out from a well-earned break to give us this update. I have seen other reports about the current wave, but none of them come close to your level of clarity and high quality of information. Very grateful to you for this and all you do. May the rest of your break be totally fun and covid free.

I'm on my way to CVS this morning to pick up a handful of tests - our daughter, home from university for over a month, feels like she's coming down with a respiratory bug. We haven't been in any elevated-risk environments over the last few weeks so I'm hopeful this isn't COVID.

I'm irritated that the CDC continues to drop reporting requirements. As far as I'm concerned SARS-CoV-2 has earned its place among mandatory reportable diseases affecting public health.

"COVID fatigue" and "election year" are weak excuses to willfully decrease vigilance. SARS-CoV-2 may never again mutate to a virulent form capable of overwhelming our hospitals with millions of mortalities, but baking a stronger stance of vigilance into our public health matrix is necessary to give us any hope of a more coherent response to the inevitable next pandemic scourge.