Note: The YLE team and I need a break. We will be taking a few weeks off, so don’t expect an email for a little while. We look forward to recharging and returning soon!

A lot of scientific questions remain about long Covid (LC). I will try to give a biannual update on the progress in our understanding, ongoing research, and what it means for you. Millions of Americans are dramatically impacted by this disease, and LC is also where most concerns lie for a majority of us when encountering Covid-19.

Here’s what we’ve learned over the past 6 months.

Note: This post builds on previous YLE posts about long Covid. If you missed those, search for “long Covid” in the YLE archive.

We finally have a definition

What we knew: The number of people who get LC after infection has ranged dramatically from 2% to 75%. Reasons for this include differing definitions—for example, some define LC as persistent symptoms 4 weeks after infection, while some use 3 months, and others 6 months.

New info: The National Academies of Sciences established a definition:

Long COVID is an infection-associated chronic condition (IACC) that occurs after SARS-CoV-2 infection and is present for at least 3 months. It can manifest as a continuous, relapsing and remitting, or progressive disease state that affects one or more organ systems.

Why does it matter? This will greatly enhance the identification and treatment of LC because all researchers working on it will measure the same thing. About time!

We still don’t know how many people have LC, though

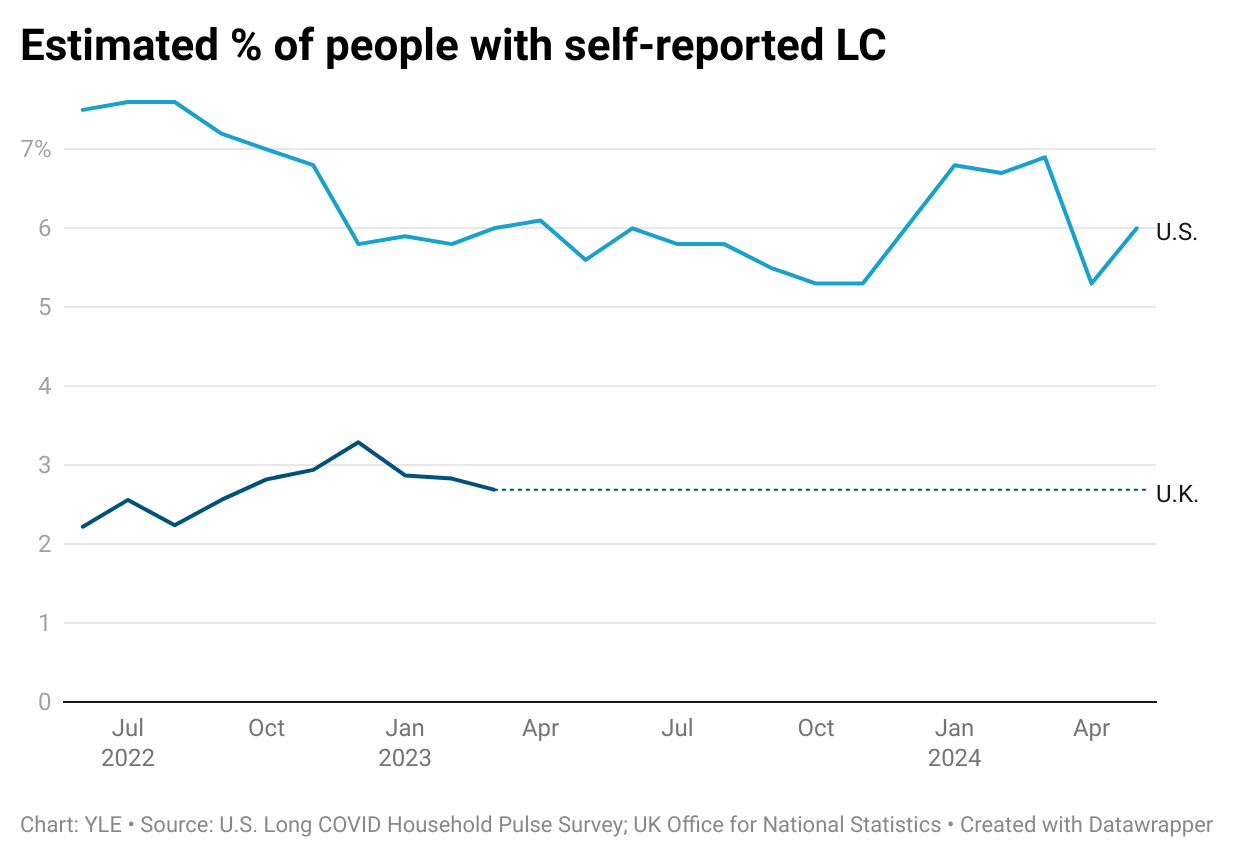

What we knew: The general public is rightfully curious about the risk of LC after infection. Scientists hypothesize it’s decreasing (thanks to immunity). Unfortunately, data is limited. The U.S. Census publishes LC estimates over time to watch trends.

New info: The number of people experiencing LC has decreased slightly since 2022 but since stabilized. (Unfortunately, UK data stopped in March 2023.) This would suggest that risk has decreased, but immunity protection may hit a threshold.

The problem is this survey is imperfect. We can’t look at that y-axis and say, “6% of people get LC after infection.” The risk is likely smaller. This survey doesn’t have a comparison group, so people can have symptoms similar to LC, like fatigue, but caused by something else. This survey also has a 6% response rate (6 out of 100 people asked to take it took it), which biases the numbers.

Why does it matter? LC remains a risk of Covid-19 infection. How big of a risk? We aren’t sure, but likely smaller than 6%. Is that risk decreasing? We think so, but don’t have good visibility.

A huge piece of causal evidence in mice

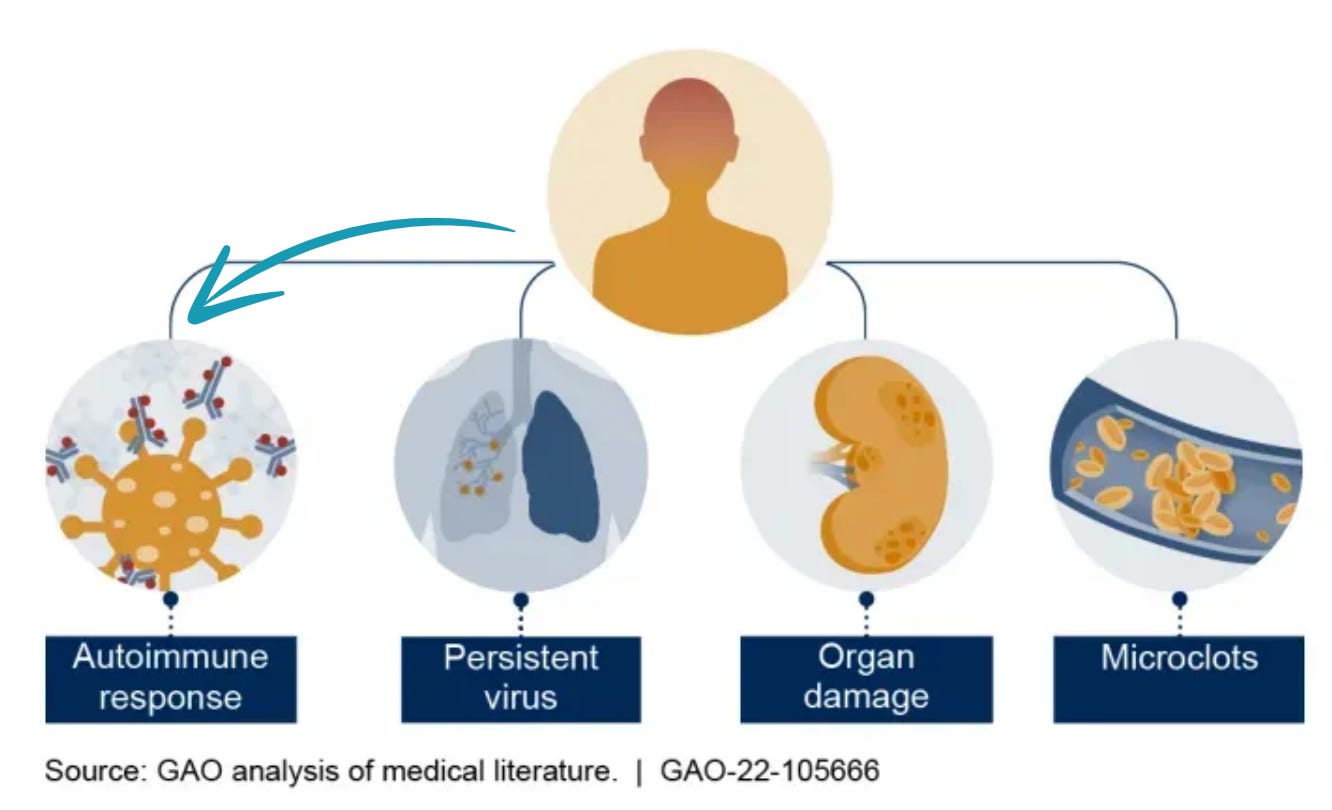

What we knew: LC is likely developed in several different ways (see figure below). One hypothesized pathway is autoimmunity—after infection, some antibodies called autoantibodies turn and attack the body’s cells and tissues. But, we’ve only had correlational studies—people with high autoantibodies also had higher rates of LC.

New info: Two new mouse studies have shown a causal link between autoimmunity and LC. Scientists transferred autoantibodies (antibodies that incorrectly attack human cells) from LC patients to mice. The autoantibodies were detected in various tissues of the mice, including the heart, skeletal muscles, spinal cords, and neurons. Also, mice replicated neurological symptoms, muscle weakness, balance, and coordination issues after the transfer.

Why does it matter? Causal evidence slingshots our understanding of the role of autoimmunity for at least a subset of LC patients, paving the way for treatments like immunotherapies.

Clues on brain fog

What we knew: Multiple studies have shown that a SARS-CoV-2 infection disrupts the blood-brain barrier (BBB), allowing substances from the blood to enter the brain. This isn’t too surprising, as many viruses can do this. However, LC patients with brain fog have more of these substances in the brain.

New info: A new study examined brain circulation among a subset of LC patients and compared it to non-LC patients. LC patients who reported brain fog had more areas in their brains where blood vessels were “leaking.” They also had more blood clotting. (Interestingly, both LC and non-LC patients in the study showed reduced brain matter volume compared to uninfected patients, indicating these changes do not primarily cause fatigue and cognitive impairment.)

Why does it matter? Therapy targets related to BBB could potentially help LC patients with brain fog, paving another pathway for treatment.

Vaccination reduces LC even if vaccinated after infection

What we knew: Several studies have shown that unvaccinated people are at higher risk of developing LC compared to vaccinated people. However, the degree of protection vaccines provide varies significantly across these studies.

New info: A new systematic review of more than 600,000 people found vaccines before and after infection reduce risks of LC:

Vaccination before infection: 10 (out of 12) studies showed that vaccination reduced LC. But you need to keep up with vaccinations—one dose didn’t seem to help much.

After infection and/or LC symptoms: Five (out of five) studies showed that vaccines prevented and helped reduce LC symptoms.

Why does it matter? Stay up to date on your vaccines to reduce LC risk.

Another study shooting down Paxlovid

What we knew: Evidence on Paxlovid’s ability to reduce LC has been mixed. This may be due to studies being limited to a short course of the medication (5 days).

New info: LC patients were randomized to receive a 15-day course of Paxlovid or a placebo. After 10 weeks of the trial, there was no statistical difference in LC symptoms.

Why does it matter? Unfortunately, this adds to the evidence that Paxlovid is ineffective against LC. It may still work for LC symptoms caused by viral reservoirs (rather than, for example, autoimmunity), but overall, more resources should be invested into other targeted therapies.

Bottom line

Our understanding of LC is slowly but surely growing. Immunity may be helping reduce the prevalence of LC, but it is imperfect protection, and we still have very few treatments for the millions suffering.

Love, YLE

Big thanks to Nini Munoz, who helped “translate” several of these studies. She is a passionate science communicator and the author of TECHing it Apart.

“Your Local Epidemiologist (YLE)” is written by Dr. Katelyn Jetelina, MPH PhD—an epidemiologist, wife, and mom of two little girls. During the day, she is a senior scientific consultant to a number of organizations, including CDC. At night, she writes this newsletter. Her main goal is to “translate” the ever-evolving public health science so that people will be well-equipped to make evidence-based decisions. This newsletter is free, thanks to the generous support of fellow YLE community members. To support this effort, subscribe below:

As one that has been grappling with the “ after effects of Covid “ which are many including a cardiac arrhythmia , the saddest part is not having a definition. All the symptoms I have developed post Covid infection ( 6 infections by know , two prior to vaccination and 4 after ) which have altered my life completely from being an active almost hyper individual to one that can barely manage and is always exhausted , don’t have a real defined diagnosis with a cause and effect . It is difficult to access care and even get reimbursed for something that essentially does not exist. Even the cardiac arrhythmia, despite the many front line workers like my self who have developed arrhythmias or other cardiac symptoms after Covid , can’t be specifically traced as caused by Covid . So I went from a healthcare worker with no problems or health conditions to one that could be classified as disabled without a true cause and definition.

Gigantic thanks to you and your team for all you’ve done! Please go enjoy a well-deserved vacation.