Public health touches on all aspects of our lives, not just during a pandemic and not just with infectious diseases. Thanks to your feedback, this newsletter will continue with COVID updates but will start touching on other epidemiological topics, too. For example, violence epidemiology (where my research “lives” during the day). If you would only like COVID19 updates, go to your settings HERE and deselect “Your Local (Violence) Epidemiologist” and “Your Local (MH) Epidemiologist.”

This week, news of a mass shooting at a New York City subway station rippled through the nation. This crisis resulted in 10 firearm injuries, 5 of which were critical. The suspect eventually turned himself in to the authorities. Other than these few details, I won’t pretend to know more about this case.

But, we are starting to gather robust population-level data on mass shootings in the U.S. and patterns are starting to emerge. On the surface, mass shootings, and violence in general, seem random. But if researchers can uncover patterns, then they’re predictable. And if they’re predictable, they’re preventable.

Burden

Mass shootings (compared to other firearm injuries) are incredibly rare, but gain the most media attention and have far-reaching impacts on community-level mental health and perceptions of safety. The exact number of mass shootings in the U.S. dramatically ranges because we have no standard definition. The FBI, for example, defines a mass shooting as resulting in 4 or more people injured/dead, while a Stanford database defines mass shootings as 3+ people. Location definition also varies. Some define mass shootings as taking place only in public places, while others include private settings.

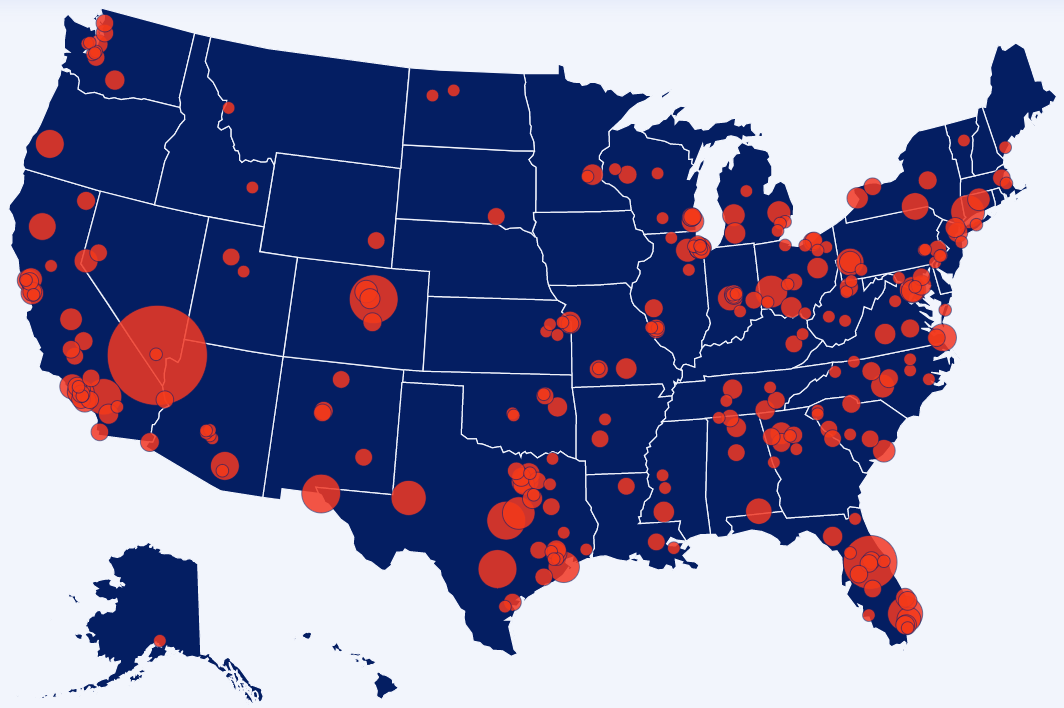

According to the Gun Violence Archive (which uses one of the broader definitions), 21 mass shootings have taken place in the past two weeks. These have resulted in 22 deaths and 111 injuries. In 2022 alone, there have been 133 mass shootings, which equates to one mass shooting every other day. Below is a map of the distribution of mass shootings from 2009-2022 using a more narrow definition.

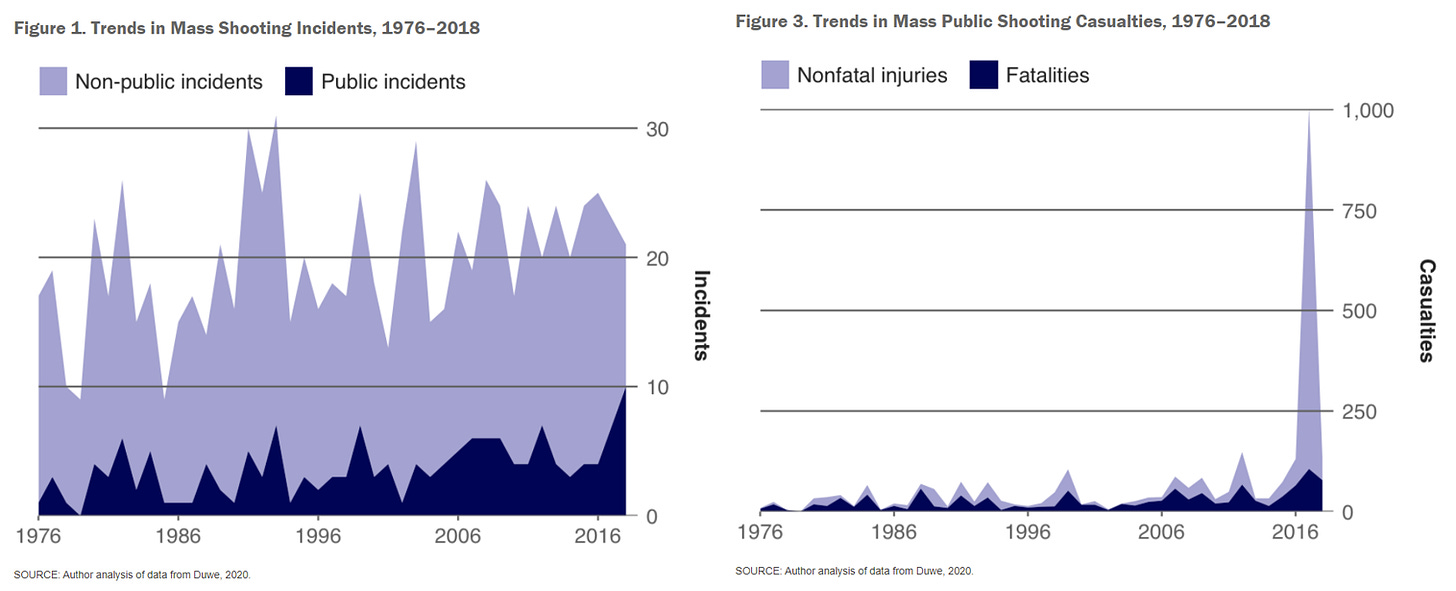

The jury is out on whether mass shootings have increased over the past decades. As one RAND report pointed out, the number of mass shootings hasn’t changed much since the 1970s, but there is a slight uptick in public mass shootings. The highest incidence of mass shootings was in the late 1980s. While the number of fatalities is also staying relatively stable, mass shooting injuries (i.e., not deaths) have skyrocketed. This was mainly driven by the Las Vegas, Nevada, mass shooting in 2017, but even when we remove this outlier, there is a positive trend.

As these figures display on the y-axis, mass shootings are rare in terms of absolute number. The annual rate is about one incident per 50 million people in the U.S., accounting for <1% of firearm injuries in the U.S. But, even if it’s “rare” it’s far more common in the U.S. than other countries. Unsurprisingly, we just have access to a lot more guns compared to other countries: about 120 firearms per 100 people. (Yemen is the second highest with 52 per 100 followed by Serbia at 39 per 100). And, firearm purchases (measured by background checks) increased during the pandemic in the U.S.

Correlates

Our understanding of mass shooting correlations is in its infancy due to lack of research funding (see more on my previous post). These are rare events, too, and rarity translates to uncertainty in statistical terms. In addition, the vast majority of studies (if not all) are descriptive, so we can’t conclude causality. But describing patterns is an important first step. And this is what we’re seeing:

Demographics. Close to all (98%) of mass shooting perpetrators are male and the majority are non-Hispanic White (61%) and under the age of 45 (82%), which is higher than the distribution of these characteristics in the U.S. general population. (Notice we are already “off” in describing the New York subway suspect. Correlation doesn’t equal causation).

Motivation. The motivations for mass shootings have changed over time. By far, the most common motivation is domestic. This isn’t surprising given domestic violence, overall, is incredibly common (1 in 4 women and 1 in 9 men are victims). Since the 2000s, hate and fame-seeking motivations for mass shootings have significantly increased.

Timing. School shootings tend to occur in Jan/Feb, May, or Sept/Oct. Notice these are all months in which there is a transition to/from school breaks. School shootings also disproportionately occur on the 20th day of the month (due to copycats of Columbine) and disproportionately take place in the morning. For workplace mass shootings, these typically occur in December and Wednesday/Thursday of the week.

Planning. The most consistent pattern is that the vast majority of these events are planned. An FBI report found that 60% of mass shootings were planned more for more than a month. Another study found that among the deadliest mass shooters (those with 8+ victims), 50% were being planned for more than a year.

Leaking. Importantly, 44-50% of mass shooters leaked their plans through social media or by telling friends or family. Among school shootings, more than 78% of mass shooters leaked their plans.

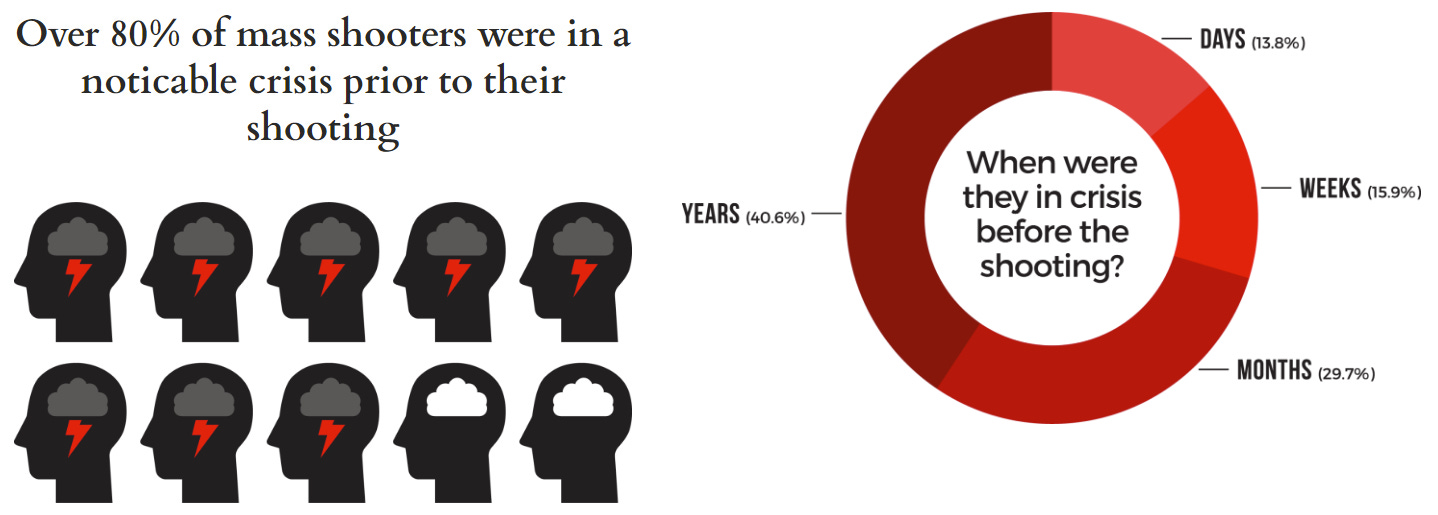

Crisis. The Violence Project found that more than 80% of mass shooters were in a noticeable crisis prior to their shooting, with more than 2/3 experiencing increased agitation and 40% with abusive behavior. Psychosis played no role in 70% of mass shootings.

Prevention strategies

Once we have correlations, we can start developing and testing evidence-based prevention strategies. For example, leakage can be a critical moment of intervention to prevent gun violence. This may be particularly true among kids. If we increase knowledge about leakages (what to look for, what’s harmless vs. harmful) and create opportunities to report threats of violence, we may be able to prevent some mass shootings. Some fantastic networks have already been established like Say Something, which was created after Sandy Hook.

There are many, many more interventions that have the potential to reduce mass shootings, as well as other firearm injuries like suicides and accidental injuries. However, researchers need the support to rigorously explore innovative and effective solutions. After decades of no funding (read the frustrating history on my previous post), in 2020 —for the first time in 25 years—our federal budget included $25 million for the CDC and NIH to research gun-related deaths and injuries. Just this week, the Biden administration proposed an additional $60 million for “researching gun violence as a public health crisis.” While this is a great step, it isn’t enough. A 2017 study estimated that we need $1.4 billion to curb the firearm epidemic as a whole (mass shootings as well as suicides, homicides, and unintentional injuries). For context, the NIH gets $6.56 billion allocated for cancer research.

Bottom line

Mass shootings are incredibly tragic. And, they are preventable. We, as a nation, need to make up for lost time by leveraging stakeholder perspectives, strengthening community partnerships, and testing and implementing effective prevention strategies to save lives as soon as possible.

Love, Your Local (Violence) Epidemiologist

Disclosures: Dr. Jetelina receives funding from Safe States for research on safe gun storage.

“Your Local Epidemiologist (YLE)” is written by Dr. Katelyn Jetelina, MPH PhD—an epidemiologist, biostatistician, professor, researcher, wife, and mom of two little girls. During the day she has a research lab and teaches graduate-level courses, but at night she writes this newsletter. Her main goal is to “translate” the ever-evolving public health science so that people will be well equipped to make evidence-based decisions. This newsletter is free thanks to the generous support of fellow YLE community members. To support the effort, please subscribe here:

My first reaction on seeing your article's headline was: "Wait... What?!" Then I read the article.

Nicely done, Dr. J. I look forward to reading more from you... on whatever you decide to publish!

This is a great introduction. It bears repeating that there is a paucity of data and research because the NRA motivated Congress to pass a law forbidding it at the CDC and elsewhere. Also a US Surgeon General's appointment was held up for a year because he had spoken up about gun violence. Now it seems the same wonderful politicians have turned their ire and disdain on needles.

Under mental health you cited the Violence Project. They, as I am sure you know, do great work and their book is a wonderful read even though the topic is grim. As my professional interest is in child abuse, I would refer you to their comprehensive spread sheet. Of the ~ 200 mass shooting perpetrators, they had good childhood histories on 66, of whom 60 had well documented abuse trauma as children. Another morbidity from that generally over looked epidemic. BTW since psychiatry does not consider childhood trauma a disease in the DSM it is often overlooked or missing in many epidemiologic studies of mental disorders as well as mass shootings.

See our

EXPERT REVIEW, Recognizing the importance of childhood maltreatment as a critical factor in psychiatric diagnoses, treatment, research, prevention, and education, Martin H. Teicher, Jeoffry B. Gordon and Charles B. Nemeroff, Molecular Psychiatry; https://doi.org/10.1038/s41380-021-01367-9