Reinfections and infections after vaccination are on the rise. Concurrently, reinfection misinformation is at an all time high. This leaves people with a lot of questions. Here is (hopefully) some clarity and answers for you.

How common are SARS-CoV-2 reinfections?

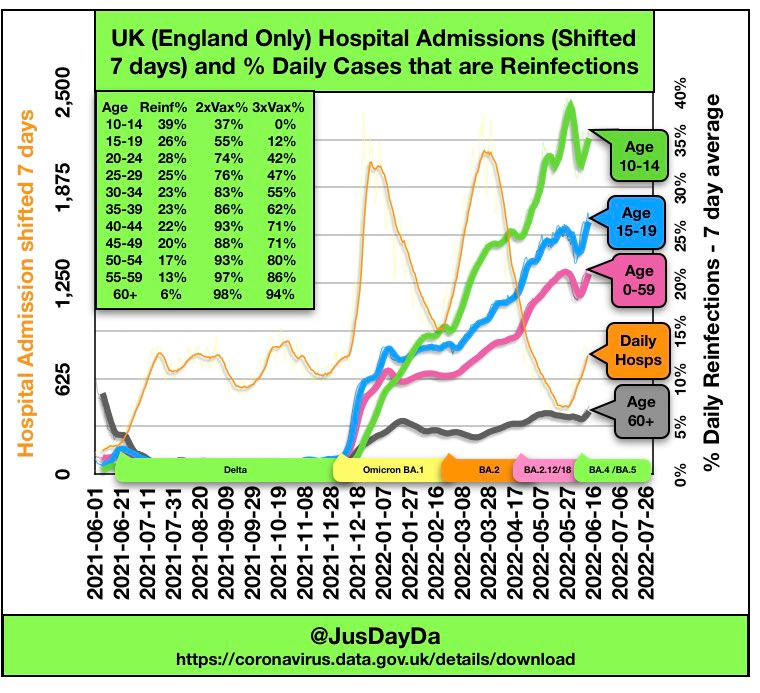

Before Omicron, reinfections were rare. In the U.K., reinfections comprised around 1% of cases in April 2021. With the introduction of Omicron, reinfection rates quickly increased to 11% of all infections. Right now, reinfections make up about 25-27% of cases in the U.K. (Remember, U.K. tracks antigen and PCR tests.)

Unfortunately, we don’t have a national picture of reinfections in the U.S. Some local jurisdictions closely follow the data. In New York, for example, ~25% of cases this week were reinfections. The rate of first infection is 28 per 100K in NY compared to a reinfection rate of 5 per 100K. Waves are still very much being driven by first infections, but reinfections are on the rise.

How do we get reinfected?

Our immune system is complex and has multiple defense walls, including antibodies, T-cells, and B-cells. Reinfections can occur for several reasons:

The virus mutates to skirt around our first line of defense—called neutralizing antibodies. Omicron keeps mutating to do this better and better. But importantly, Omicron can’t fully escape. This is why immunity can still prevent infection for some.

Antibodies wane over time, so our first wall of defense gets shorter and shorter.

Some people don’t mount an immune response after a primary, and typically mild, infection.

So unfortunately, with more transmission, a rapidly evolving virus, and a virus that recently mutated to become less severe, we can expect SARS-CoV-2 reinfections.

Who is at most risk for a reinfection?

Thanks to U.K. surveillance data, we know people are more likely to be reinfected if they:

are unvaccinated

had a “milder” primary infection with a lower viral load

did not report symptoms with their first infection

are younger (although reinfections are rising for all age groups, as seen below)

Are reinfections common with other diseases?

Immunity from some viruses and vaccines, like measles, can last decades. However, just like SARS-CoV-2, other respiratory viruses mutate more quickly and antibodies wane, so reinfections are more common. This happens with the flu, RSV, and other coronaviruses. During a regular flu season, for example, 1 in 5 people are reinfected. While children and adults can be reinfected with RSV, reinfection is associated with milder disease.

How quickly can someone be reinfected?

An early 2021 study found that people have great protection from SARS-CoV-2 in the first 90 days after infection. In fact, the CDC still uses the 90-day window to exclude counting new positives as reinfections. However, reinfections do occur earlier. A study in Denmark found that while pre-Omicron reinfections were rare (593 out of 4.4 million people), many occurred within 60 days of infection. Two additional studies (here, here) confirmed reinfections occurred as early as 20 days after infection during the first Omicron wave (reinfections remained rare; 1,739 out of 1.8 million people).

A reinfection can, theoretically, occur as soon as the virus has cleared, but clearance varies for individuals. The virus can linger far beyond the infectious period. This means you can test positive on a PCR test weeks after initial infection, but this is a reflection of the initial infection rather than a new infection. Testing positive on an antigen test a few weeks after initial infection, though, is reflective of a new infection (assuming it’s not a Paxlovid rebound).

One could theoretically get reinfected week after week or month after month, but this would be incredibly rare because it assumes no immune response after each subsequent infection. In fact, I’m unaware of a single instance of rapid reinfection described. The cadence of reinfection going forward (every 6 months? every year?) is not clear, as we are at the mercy of time, viral evolution, and booster roll-outs.

How severe are reinfections?

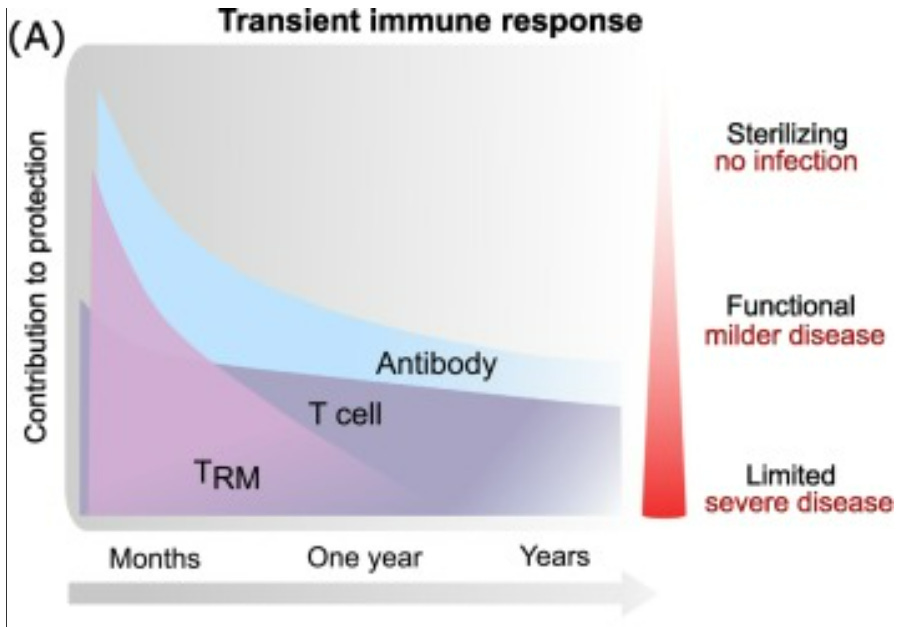

Even if our first layer of defense is down (causing reinfections), our secondary line of defense kicks in preventing severe disease. This is displayed nicely in the figure below (ignore the x-axis, as this was made for other respiratory viruses).

We continue to see this phenomenon at the population and individual level:

Population level: Population patterns show severe disease getting more and more rare with each subsequent wave. Disease is milder for Omicron than Delta, but not enough to explain this pattern. Our immunity wall is building up, causing welcoming patterns, like decreases in deaths in South Africa shown in the graph below.

Individual level: We see lower severity of disease with reinfections. Before Delta, a study in Qatar found reinfections had 90% lower odds of resulting in hospitalization or death than primary infections. Another study in the U.K. found reinfections were associated with a 61% lower risk of death than primary infections. Those who were vaccinated had lower risk of severe reinfection compared to those who were unvaccinated. In 2021, the U.K. found that viral load was significantly reduced after reinfections compared to primary infections, and thus protects against severe disease.

More recently, a Danish pre-print study evaluated reinfections after 1.8 million Delta and BA.1 infections. No reinfection resulted in hospitalization or death. Even more recently, a pre-print from Qatar found effectiveness against severe reinfection remained incredibly high (97%) through June 5, 2022. (It’s important to recognize this study population was very young and very healthy.)

What about the Veteran’s Affairs (VA) reinfection study?

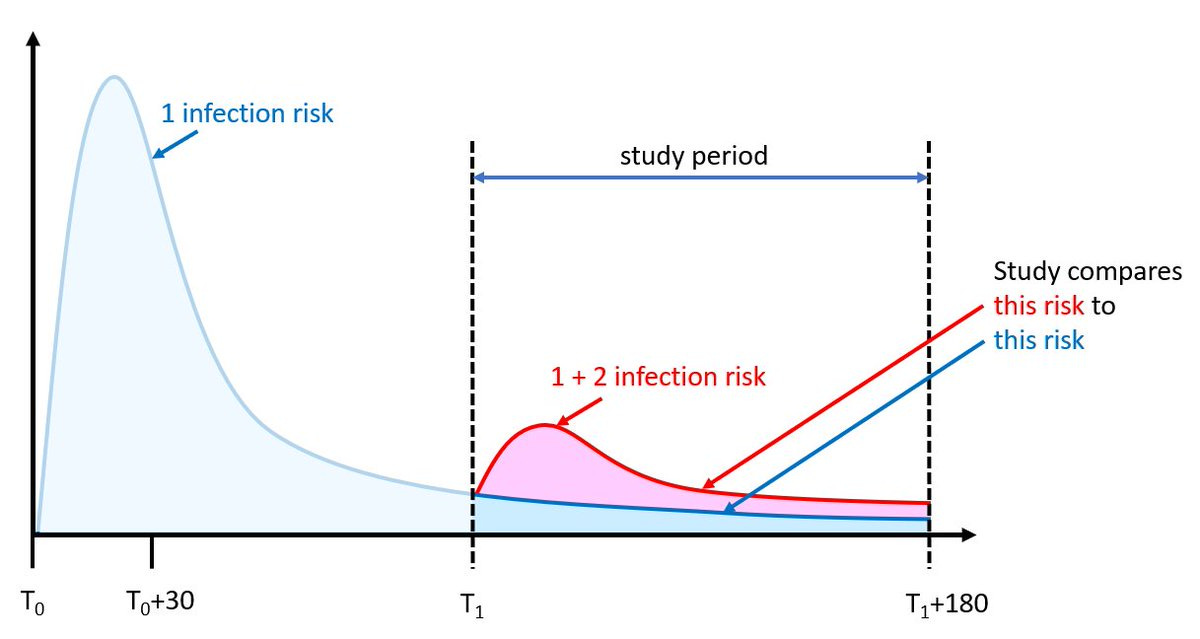

A few weeks ago, a now infamous VA pre-print was released comparing the risk of poor outcomes (e.g. death, health problems) among those with reinfections to those with primary infections. The viral pre-print sent shockwaves through media, as the study was widely misinterpreted to say the health risks from reinfections are worse than risks from primary infections. This is not what the study showed.

The authors did not compare reinfections to the same person’s primary infection. Instead they compared people with reinfections to a separate cohort of people with primary infections (see figure below). Because of this, the only thing we can conclude is that being infected again is worse than not being infected again, which is expected.

It’s also important to recognize that this sample was high risk: The average person in the study was 62 years old, 25% were smokers, 80-90% were unvaccinated, 30-40% had diabetes, and 19-26% had heart disease. Similarly, among those reinfected, 20% were hospitalized during the first infection. Among those who had three infections, 8.3% were immunocompromised (compared to 1.1% of first infections).

It’s imperative to assess severity of reinfection among high-risk groups. And, clearly, there are vulnerable pockets of people that will get severe reinfections. But, assuming reinfections are more severe than primary infections for everyone is incorrect.

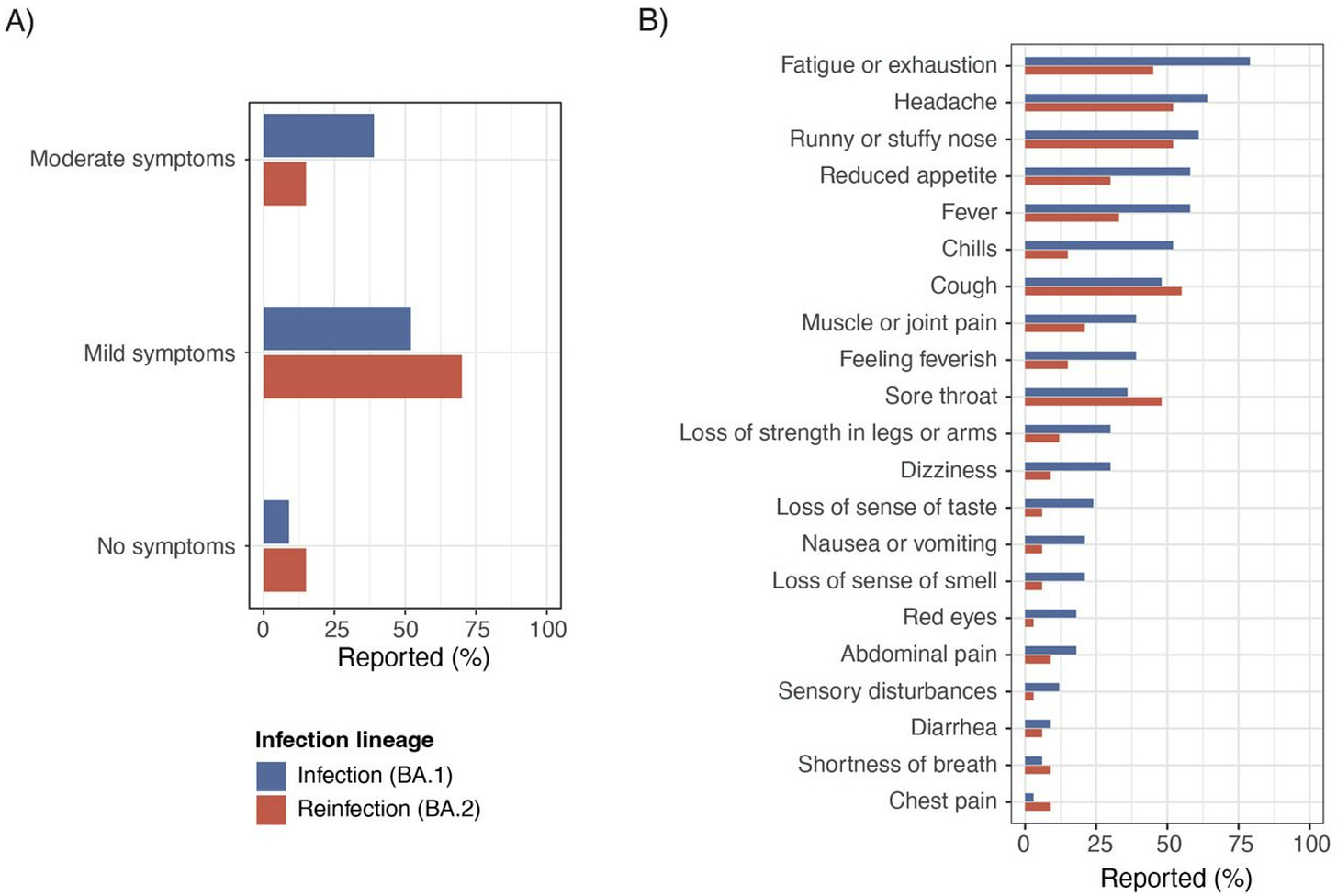

If I had a fever for first infection (moderate disease), will my response be milder with reinfection?

This isn’t very clear. A Danish pre-print evaluated BA.2 reinfections after BA.1 infections. The rate of mild symptoms was higher but the rate of moderate symptoms (defined as flu-like symptoms) was lower. This was a very small sample size (33 people), so more evidence is needed.

What about long COVID after reinfection?

We desperately need more research on long COVID, and we need to sufficiently recognize it as a risk of infection. I couldn’t find much on the risk of long COVID due to reinfections. We can hypothesize lower risk given lower viral load, but this is an educated guess and we don’t know how long COVID occurs or how to treat it.

Bottom line

There are myriad reasons we need to do our best to reduce SARS-CoV-2 transmission and prevent infection. Wearing masks, staying up to date with vaccines, and improved ventilation will help. And, ideally, reinfections would not occur. But we are well past the point of zero COVID, and reinfections can be expected, just like with other respiratory viruses. Vaccine and infection-induced immunity is clearly reducing severity of reinfection. Unfortunately, protection from severe reinfection isn’t guaranteed for high-risk groups.

Love, YLE

“Your Local Epidemiologist (YLE)” is written by Dr. Katelyn Jetelina, MPH PhD—an epidemiologist, biostatistician, wife, and mom of two little girls. During the day she works at a nonpartisan health policy think tank, and at night she writes this newsletter. Her main goal is to “translate” the ever-evolving public health science so that people will be well equipped to make evidence-based decisions. This newsletter is free thanks to the generous support of fellow YLE community members. To support the effort, please subscribe here:

I know this is likely in response to the viral, scary article being passed around widely. I always appreciate your sane and comprehensive write-ups! Couple of curious questions ...

1) If re-infections are rare -- maybe at most ~27% of infections -- shouldn't we be running out of folks who've never been infected before? For example, we know that the number of people who've ever been infected in those under 18 in the US as of Feb 2022 was around 75% IIRC. Is it still possible that today (or very recently) 75% of new cases in those under 18 are from that incredibly shrinking 25% who had never been infected?

I know anecdotally, I don't have many friends who've still never caught COVID.

Methodologically, if we're not great at counting actual cases (I see some reputable people apply a 5x multiplier to current case counts in the US to estimate actual cases), wouldn't it also stand to reason that we've even more terrible at counting re-infections? It would be like lighting striking twice. I guess my question is whether or not we're undercounting cases and then by extension (squaring the probability), very much undercounting re-infections.

I feel like if reinfections were actually as rare as these numbers suggest, we should be running out of new folks earlier this year.

2) Part of the public horror about the danger of re-infection is that it goes against the public's prior understanding of the risks. Many folks believed it was "one and done" and there was some value to simply "getting it over with." Likewise, if there was some rare change of a re-infection, it wasn't anything to worry about because someone already had immunity.

I think the reason that article (as careless as it might have been with language and hyperbolic) went viral was because it was making a few key points. 1) It isn't one and done. The virus mutates more quickly than expected. Reinfections can definitely happen and they can even happen on a surprisingly quick timeline. 2) Re-infections pose some additional health risk. Whether that risk is the same as the initial infection or to a lesser degree, there is *some* additional risk associated with getting re-infected. Which leads to 3) Unmitigated transmission is a problem (both for individuals and society) and no matter your prior infection history, you should continue taking active steps to minimize your total number of infections. Even if you've had it, you should keep from getting it again. It's not necessarily "no covid" (almost impossible to avoid), but our philosophy needs to be "low covid" (as few infections as possible).

The well-intentioned "take-downs" I see of that article seem to miss the gist behind why it went viral in the first place.

How concerned should we be about cumulative risk (longer term) of multiple infections? I think this is a key point. It’s been such a struggle to get the general population to see that taking reasonable precautions to avoid infection and reinfection as we learn more about a novel virus is a reasonable goal for overall health at any age.