Happy August! I’m back from summer vacation. My little family explored all three gorgeous national parks in Washington State, which required much-needed unplugging.

The YLE team is refreshed and ready for the fall season! I hope you are, too. Let’s dive into the state of affairs.

Covid-19: Up, up, and away

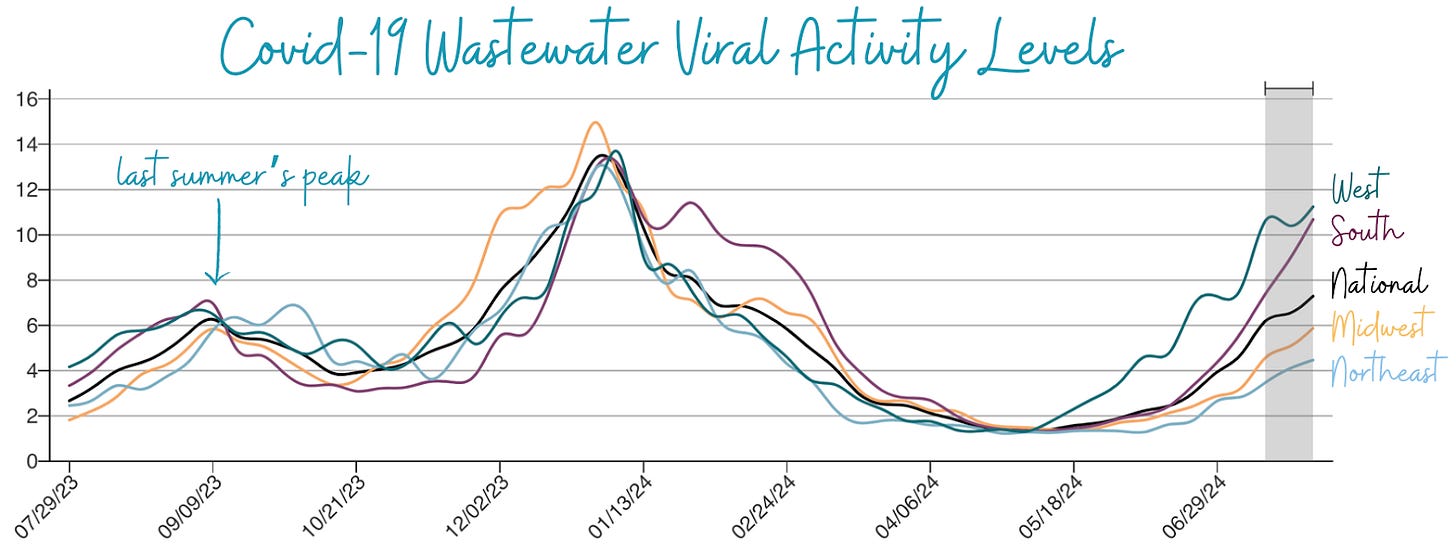

We are knee-deep in a substantial Covid-19 infection wave. Wastewater levels—a good indicator of community spread—remain high and continue to increase, especially in the South and the West, where levels are coming close to last winter's.

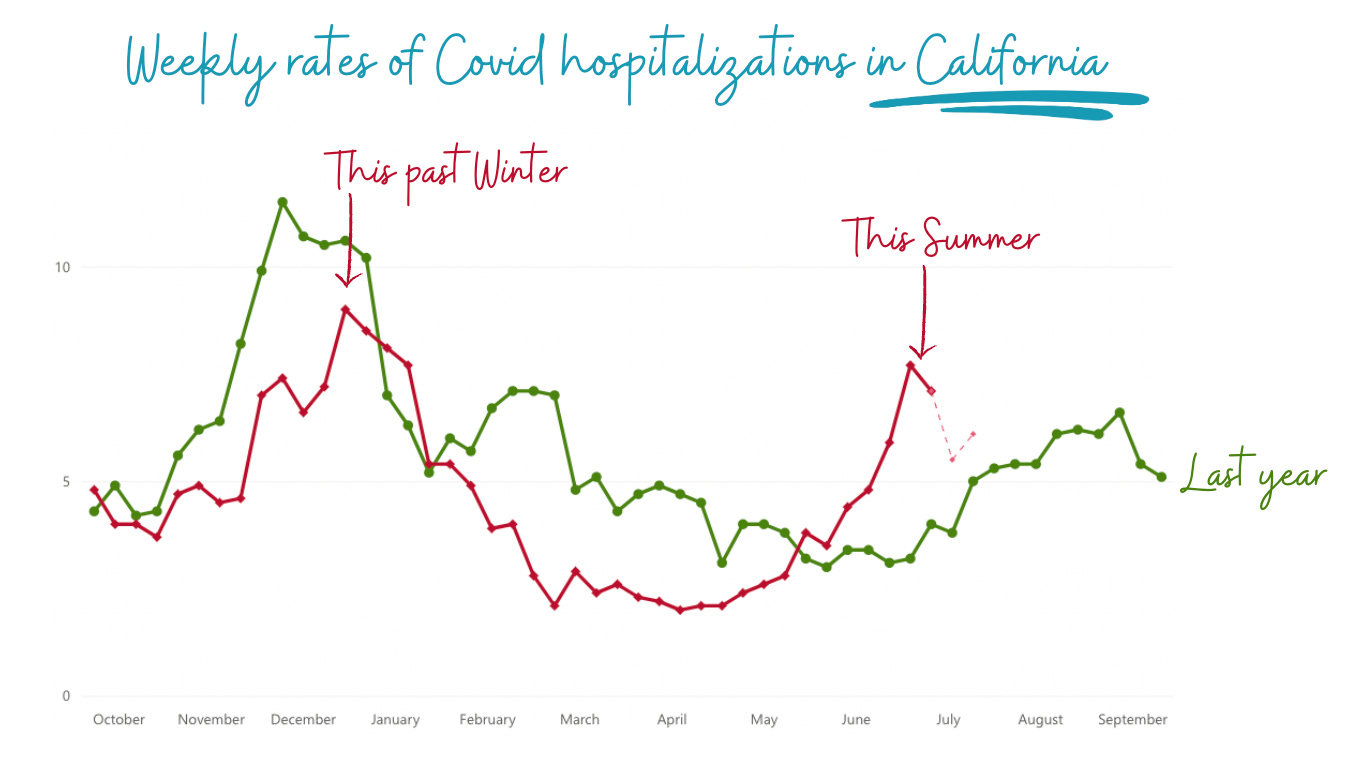

Thankfully, immunity keeps our hospitals from overflowing at this point, but severe disease trends continue to mirror infections. For example, in California, hospitalizations this summer are as high as last winter.

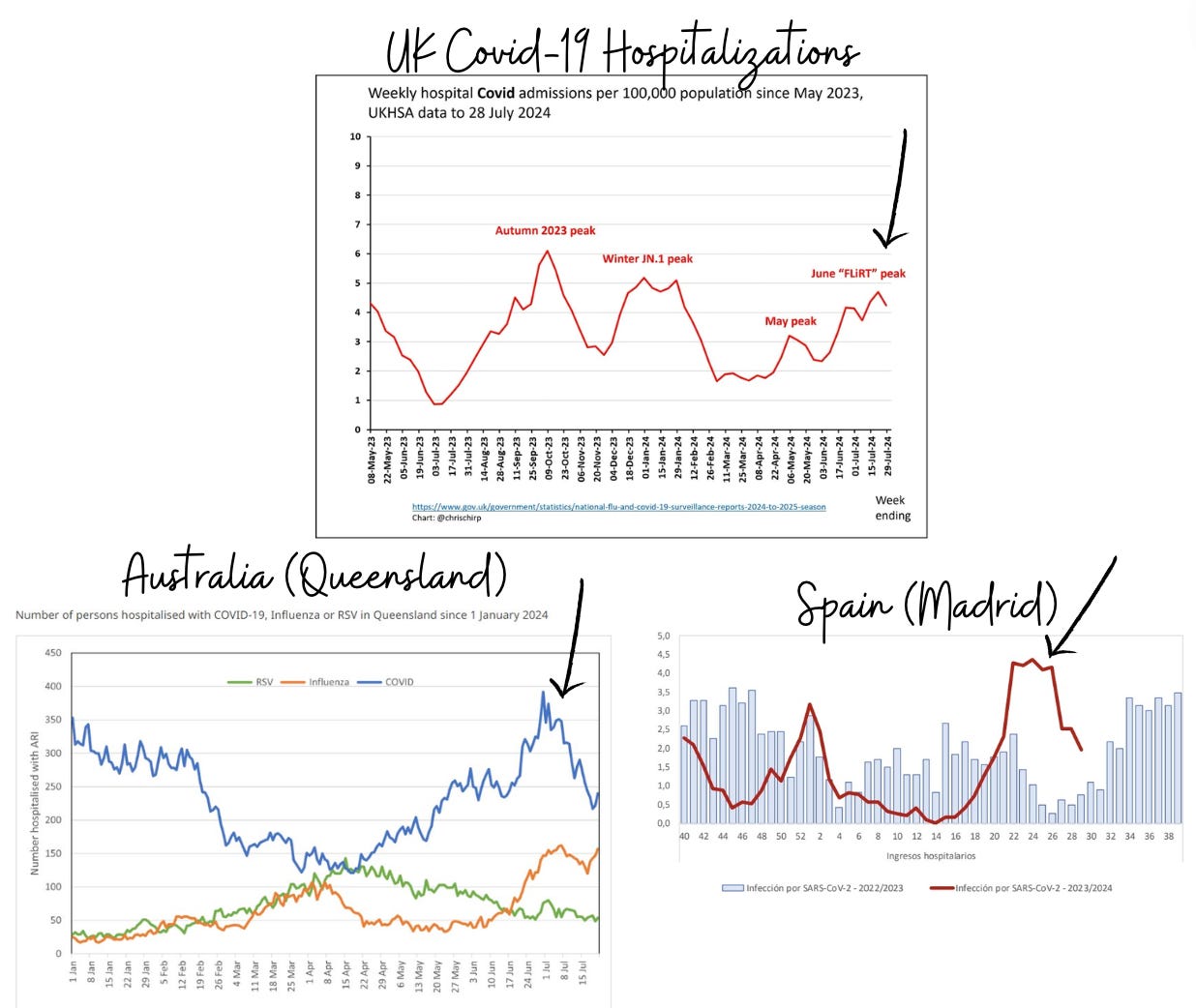

This pattern—2024 summer rates reaching winter rates— is not unique to the U.S. Covid-19 hospitalizations in the U.K., Spain, and Australia all show similar trends.

The height of this summer wave is surprising to me, as we would hope that summer waves get smaller and smaller over time. So, three unanswered questions are top of my mind:

Why is this happening? I don’t know. The newest subvariant doesn’t have so many mutations that I would predict this would happen. Vaccination rates are about the same as last year, which also wouldn’t explain it. Could this be due to the CDC changing its isolation guidelines to be more relaxed in February? Probably not, given similar patterns in other countries.

Will we have a milder winter? We can hope that the immunity we have built up will lead to a milder winter, which would be a welcome reprieve to health systems.

Are biannual waves the future? Many (including me) hypothesize Covid-19 will eventually become a winter virus, like flu. But clearly Covid-19 is still unpredictable and will likely take another decade to find a rhythm.

Other updates

Epidemiologists are monitoring these other viral outbreaks. You have nothing to do, but here is an update so you can follow the scientific discovery ride.

H5N1 (bird flu): Continues to spread

We are keeping an eye on H5N1 because of the potential for it to become a pandemic.

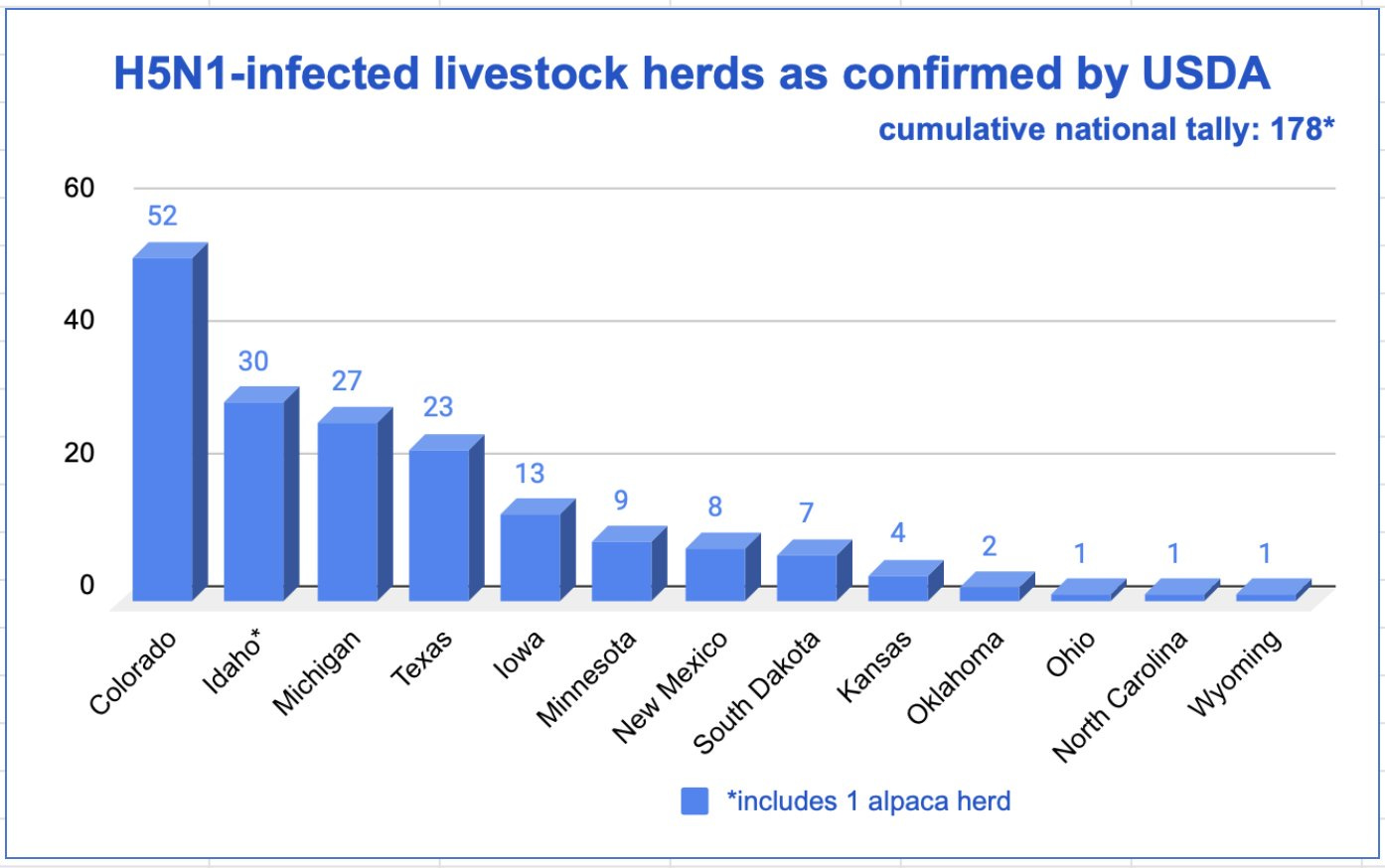

H5N1 continues to spread among animals. USDA has reported 171 dairy cow herds in 13 states with confirmed H5N1 infection.

Four big developments have occurred since the last YLE update.

More humans have been infected, but no onward spread. This year a total of 13 people have been infected with bird flu: four from sick dairy cows and nine from poultry. This is a lot of cases, considering U.S. had 1 H5N1 human case last year and zero before. The human tally recently increased thanks to a big outbreak in Colorado, when several workers got sick after culling (killing) infected poultry. As far as we can tell, this outbreak wasn’t because the virus mutated; instead, it was the environment—it was over 100 degrees at the farms, so workers didn’t wear PPE (understandably), and massive industrial fans to cool the area spread feathers (and virus). So far, cases have been mild (red eye and respiratory symptoms), and there is no ongoing human transmission.

We are missing human cases. Given our limited human (and animal) testing, it shouldn’t be a surprise that we are likely missing human cases. In Texas, scientists tested the blood of 14 previously symptomatic farm workers and found 2 workers had antibodies. This could be evidence that they had H5N1 at one point. (However, it’s also possible because of the type of test used that these antibodies reflect infections from seasonal flu [H1N1]). We don’t think there is an asymptomatic spread. Another study in Michigan tested the blood of 35 workers who were exposed to infected herds but never had symptoms, and none were positive.

There are no signs of it “burning out.” The genetic sequences of bird, cow, and human cases suggest the U.S. has created a new reservoir of H5N1 that can spill over into poultry and humans all year round.

All eyes are on the upcoming seasonal flu. If one of these farm workers gets infected with H5N1 while sick with seasonal flu, the risk of a pandemic skyrockets, as the virus can easily swap genes to become more adaptable to human spread. CDC is funding an extensive seasonal flu vaccine campaign for farmworkers to prevent a nightmare.

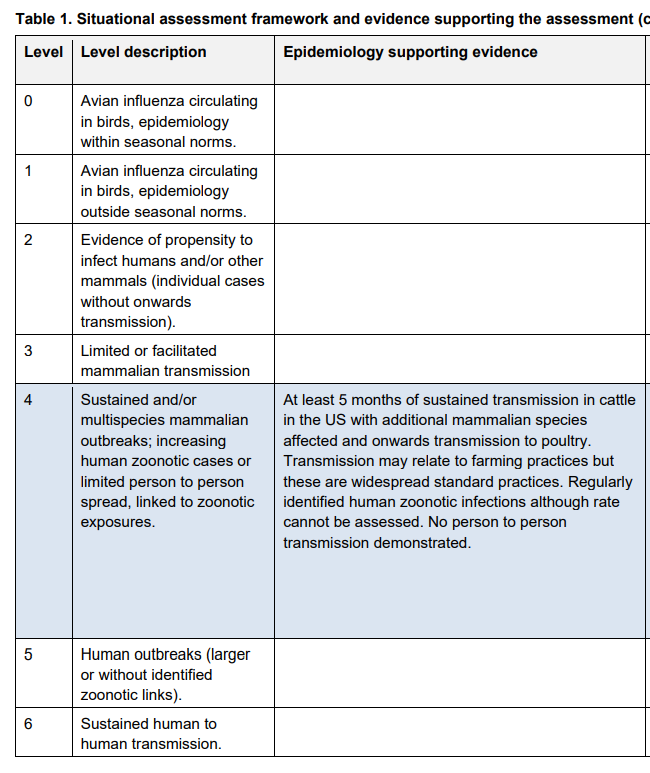

We still don’t have an updated CDC risk assessment of an H5N1 pandemic (called iRAT), which is surprising. (The last iRAT was published in April 2023 after minks were infected in Spain. They rated the pandemic risk as “moderate.”) The U.K. recently raised their risk assessment (from 3 → 4) given the U.S. outbreak.

Mpox (Monkeypox): Surging in Africa

The WHO is considering naming the ongoing mpox outbreak a public health emergency of international concern.

Case counts continue to explode in Africa, with over 37,000 cases and 1,400 deaths. The Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) has been the epicenter, accounting for over 96% of this year’s cases and deaths. The vast majority of deaths (85%) are among children. The Africa CDC has heightened its monitoring and declared the risk “high.”

In a surprising turn of events, mpox has mutated. Mpox is primarily divided into two clades (types): Clade I and Clade II. Clade I, found predominantly in Central African countries, tends to be more severe. The new strain, called Clade 1b, is severe and can be transmitted human to human.

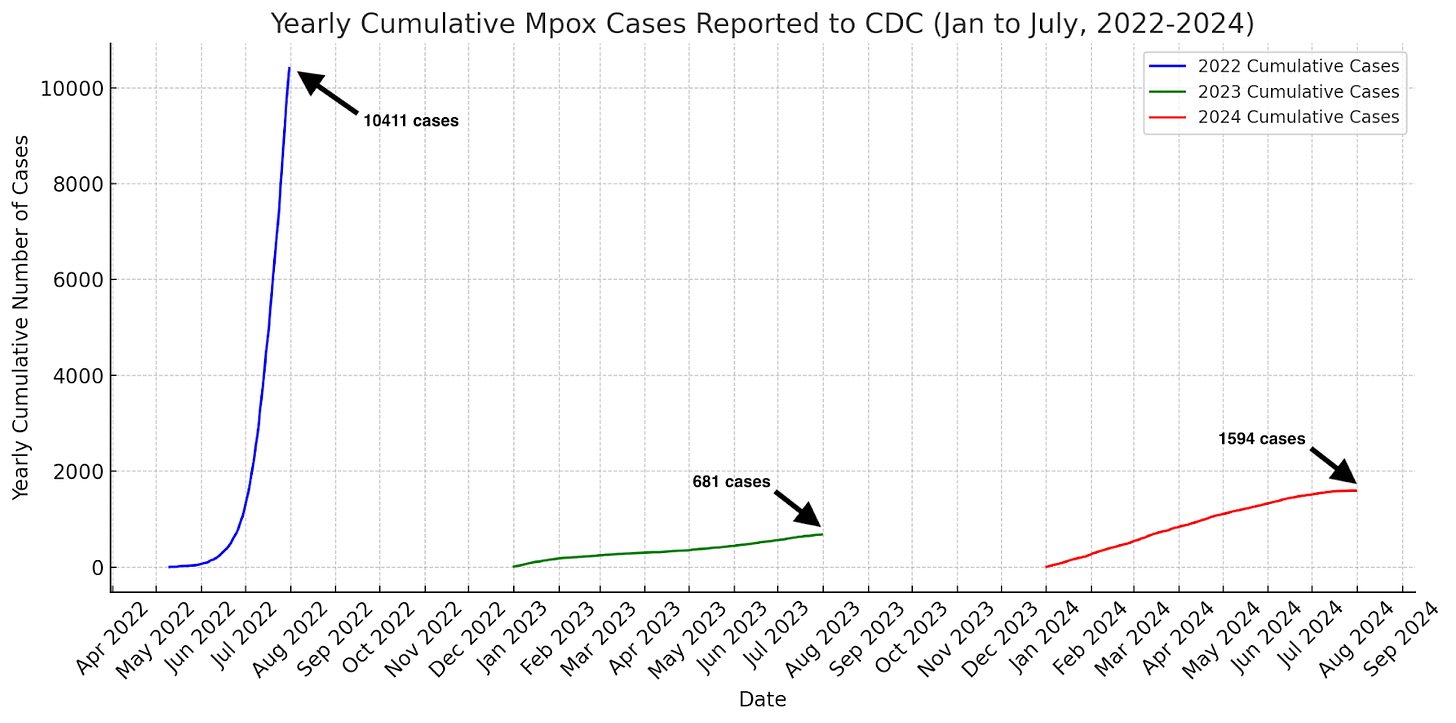

Unfortunately, many patients in Africa lack the resources that can keep mpox at bay, like vaccinations, treatments, and access to care. In the United States, for example, where only Clade II—the less severe strain—is spreading, cases are far lower than in 2022. Even if the more severe strain landed in the U.S., we don’t think it would be as detrimental as it is in Africa.

Bottom line

Covid-19 infections are surging this summer. There are things you can do—stay up to date on vaccines, mask indoors and in crowded areas, and get that indoor air flowing. Concurrently, H5N1 continues to march into the upcoming flu season, increasing the risk of another pandemic, and WHO is considering another mpox emergency. As always, we’ll keep you updated as things change.

Love,

The YLE Team

This post was a team effort at YLE crafted by Andrea Tamayo, Sarah Gillani, and Katelyn Jetelina. Our main goal is to “translate” the ever-evolving public health science so that people will be well-equipped to make evidence-based decisions. This newsletter is free thanks to the generous support of fellow YLE community members. To support this effort, subscribe below:

I understand that vaccines take time to make, but I don’t understand why the updated fall ‘24 booster won’t be released until *after* the summer surge.

If Public Health wants people to take Covid boosters once (or twice) a year, they need to be released *before* the surge.

Welcome back from what sounds to have been a beautiful—and certainly well-earned-vacation. You and the team have once again given us a clear, informative report. I have been curious to see that the Northeast region remains lowest on COVID and wonder whether it is escaping the worst of the wave, or whether the wave is just late in coming. I also found your report on the H5H1 tremendously informative, including getting “under the hood” on the efforts CDC is making, which are usually invisible to the unaffected public. It is very sad to learn of the wave of monkeypox in Africa, also something about which I have seen nothing elsewhere, but which I hope is getting strong attention from appropriate governmental and humanitarian agencies.