For this post I partnered with Dr. Jon Levy, Professor and Chair of Environmental Health at Boston University School of Public Health, who has been working on this topic for decades. Also special thanks to Luis Melecio-Zambrano—a science journalist and student—who helped me “translate” the scientific story.

On January 9, someone at the Consumer Product Safety Commission (CPSC) mentioned in an interview that they were looking to revise safety standards around gas stoves, saying, “Any option is on the table. Products that can’t be made safe can be banned.”

Two days later, the Chairman of CPSC clarified: “I am not looking to ban gas stoves and the CPSC has no proceeding to do so.” But the spark had already lit the fire of debate through the media and the halls of Congress. In fact, the new House drafted two bills to stop the “ban.”

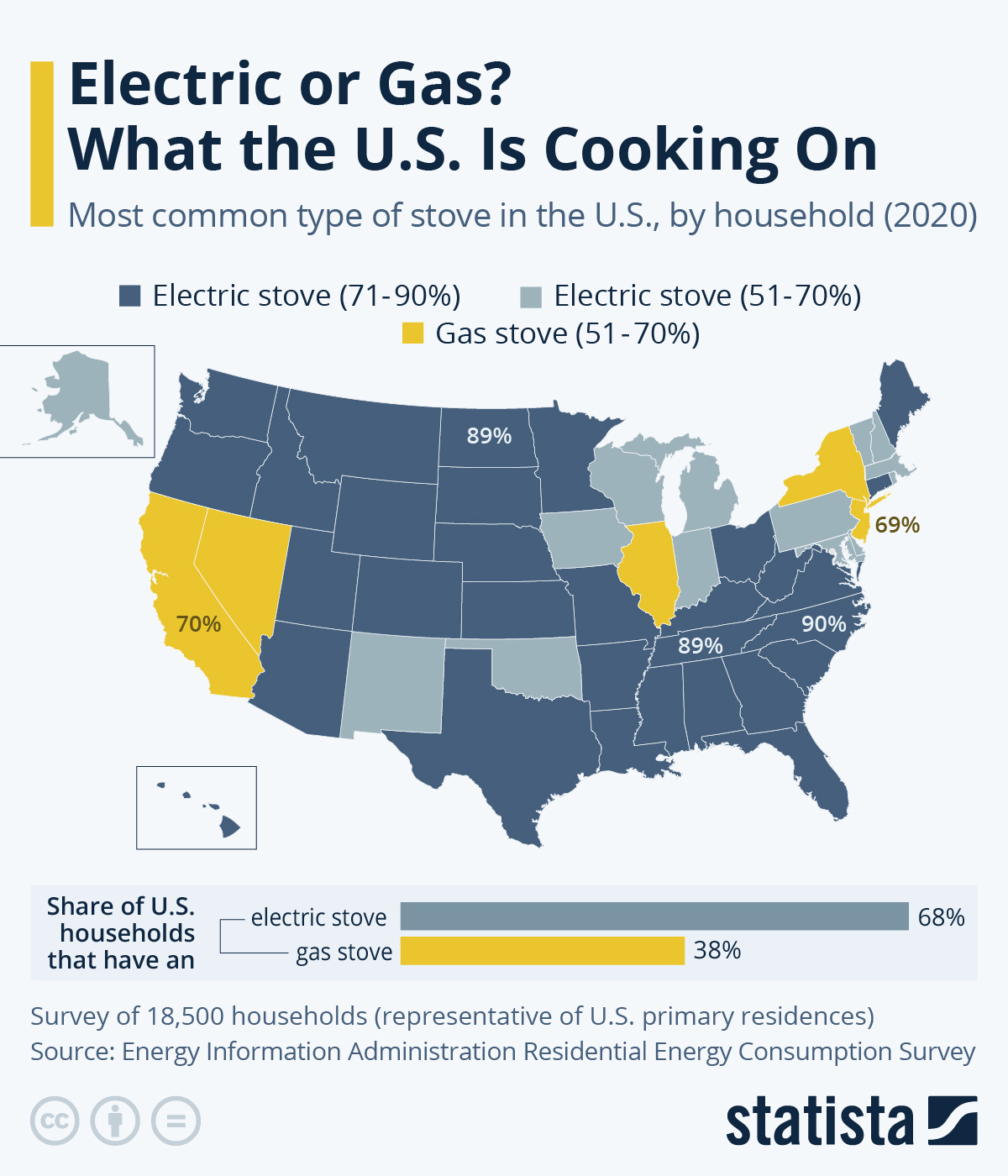

In reality, this is a major issue in only selected states like California and New York, in which more than 70% of households have gas stoves. However, as Statista reported, nearly 40% of US households use gas stoves, so this is a salient concern for nearly 50 million households across the country.

What does the science say?

This is not a new issue. Decades of research have found the same thing: gas stoves can contribute to respiratory issues, especially for children with asthma.

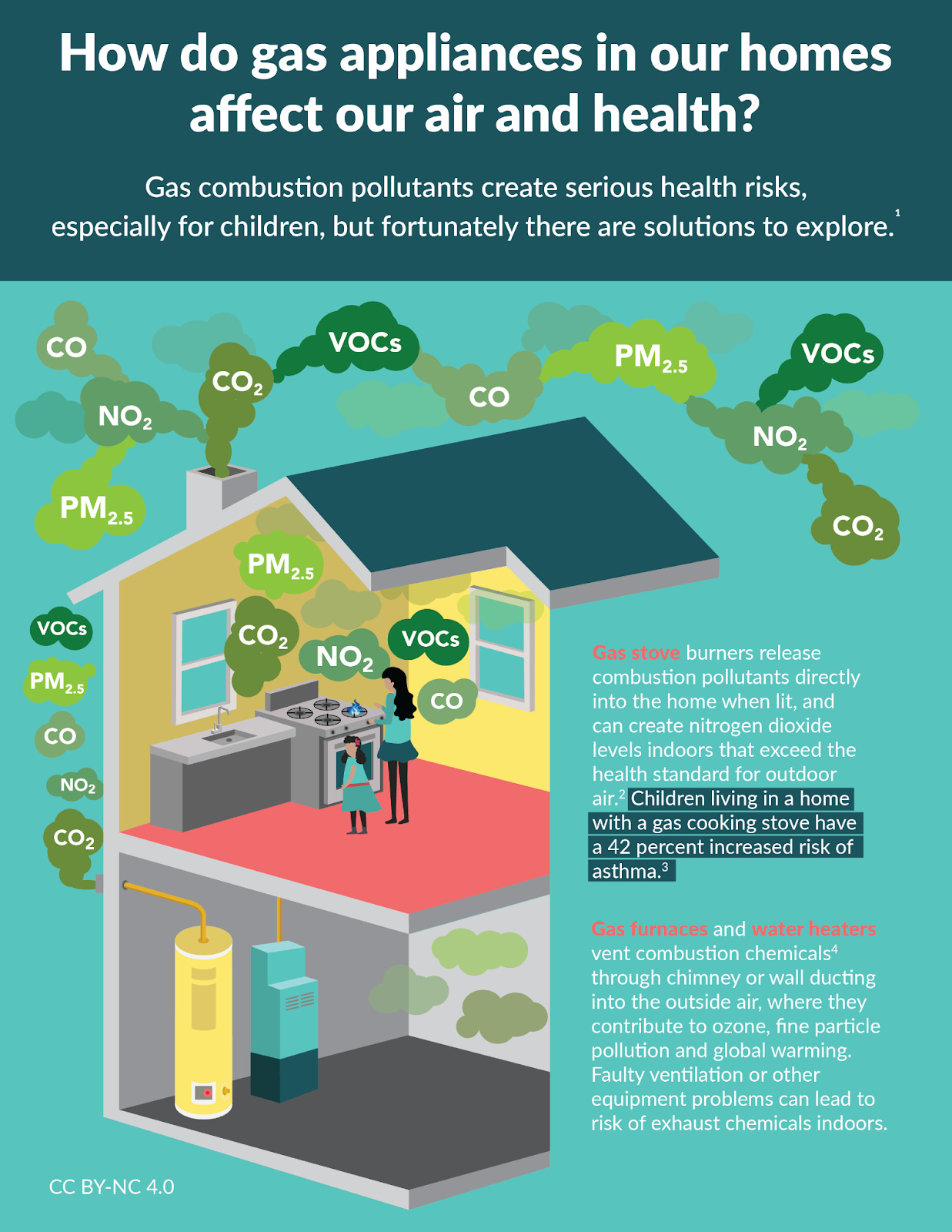

When we burn fuel at high temperatures (i.e., cooking) many different chemicals are released into the air. This includes nitrogen dioxide, which is a reddish-brown gas (see “NO2” in the figure below). When this happens in an indoor space, concentrations can get high, especially if you live in a smaller home with limited physical space and ventilation.

Studies for many decades have measured nitrogen dioxide levels in homes and found that levels were higher for homes with gas stoves. For example, a study across 15 countries in the 90s found gas stoves were a major contributor to nitrogen dioxide exposure. This is both because gas stoves contribute significantly to indoor nitrogen dioxide and because people spend a lot of time indoors at home. These patterns have been confirmed in other publications, including in a recent study in the homes of asthmatic patients.

A study in Boston public housing showed that the nitrogen dioxide levels in the kitchen were double the levels measured outside. Another study showed that in homes using gas stoves without range hoods, the nitrogen dioxide exposure around cooking time was much greater than the levels outside of the home.

Nitrogen dioxide (and thus gas stoves) and health

Nitrogen dioxide irritates the lining of our airways. In the short term, this can cause symptoms like wheezing. If this happens consistently over time, it can cause health problems like asthma and COPD.

The health evidence for nitrogen dioxide has been formally examined on a regular basis by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) as part of its process for regulating outdoor air. In 2016, its most recent summary, the EPA reported abundant evidence for nitrogen dioxide and exacerbation of asthma in children as well as development of asthma (among other health outcomes). While the focus of EPA’s summary is on outdoor nitrogen dioxide, since that is all that the EPA regulates, it’s noteworthy that we are exposed to the same pollution indoors, often at higher levels in the presence of gas stoves.

Why is this a “thing” now?

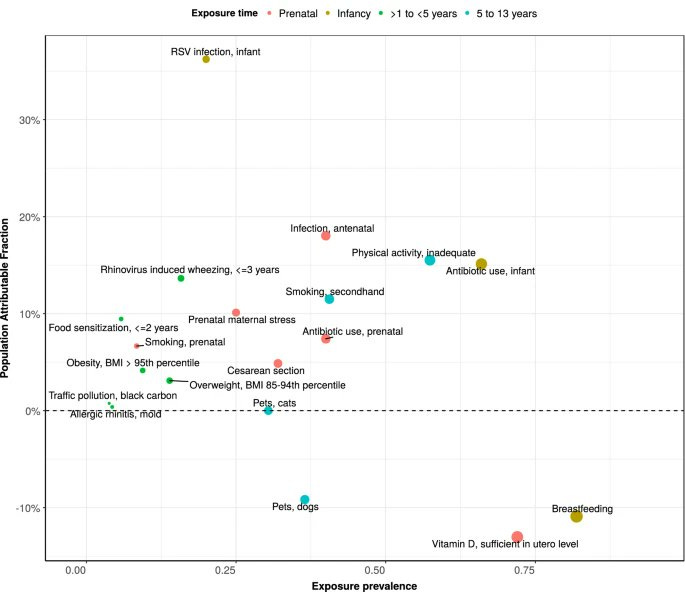

The most recent debate around gas stoves was sparked by a 2022 study by U.S. and Australian researchers. They estimated that nearly 13% of current childhood asthma cases in the U.S. were attributable to gas stoves in homes. In other words, if we remove all gas stoves in the U.S., we could prevent ~13% of childhood asthma. (As one author of the study noted, this percentage is similar to asthma attributable to secondhand smoke among 1 to 5 year olds.)

The foundation of the gas stoves study was a 2013 publication in which researchers analyzed more than 40 studies. They concluded that children living in households with gas stoves were 42% more likely to experience asthma symptoms and 24% more likely to ever get diagnosed.

Just like other public health problems, the industry is fighting back. This was highlighted over the weekend when the New York Times uncovered that lobbyists were hired by gas companies to sow public doubt in the health dangers of gas stoves. Their main argument: the health studies like the ones in the meta-analysis don’t establish causality. In other words, we don’t know if gas stoves directly lead to asthma, or if some other factor explains the findings.

Of course not every study is perfect. But the studies of gas stoves and asthma are built on a foundation of 40+ years of studies linking gas stoves to nitrogen dioxide exposures and nitrogen dioxide exposures to respiratory health. The case for causality is strong.

What does this mean for me?

Individuals should weigh the benefits of their gas stove with the risks:

Benefits: Many people cannot swap out a gas stove right away because they are renting, it’s cost-prohibitive, or just logistically challenging. It can be cheaper to use a gas stove than an electric one, especially when electricity prices are high. Gas stoves come in handy when there is a power outage. And some people just enjoy cooking with a flame.

Risks: If you do have a gas stove, it could be a large contributor to your nitrogen dioxide exposure, especially if you live in a smaller home with inadequate ventilation. There are real health risks, especially for children and people with asthma. Gas stoves contribute to other pollutants in the home beyond nitrogen dioxide, and there are risks of gas leaks. There are also climate risks (which impact health down the road, too).

Those who have the opportunity and can take advantage of financial incentives should consider making the switch to electric. If that’s not possible, improve ventilation:

If you have a range hood or other exhaust fan, run it when you are cooking. They help. However, not all range hoods are equal. For example, you need one that has a strong enough fan that vents to the outdoors.

Open windows when cooking. This is a smart strategy even if you have a range hood. Unfortunately, range hoods don’t completely eliminate risk. A 2012 study found that range hoods remove less than half of the pollutants emitted by gas stoves.

What does this mean for my community?

There are several actions we, as a society, can also take:

Financial incentives to move away from gas stoves. There are multiple programs already in place that incentivize the swap-out for climate reasons, including through the Inflation Reduction Act, but the incentive should be greater considering the impact to health. One study estimated that replacing gas stoves or improving ventilation can reduce serious asthma events by around 7%, which can save considerable health costs. Medicaid, for example, should take note.

Improve range hood performance. Range hoods that are successful in reducing pollution from gas stoves sometimes produce prohibitive noise levels, resulting in them being used less. We need improvements in hood design.

Require ventilation to the outdoors when a new stove is installed. We need more homes to have range hoods with outdoor ventilation in place.

Bottom line

The government isn’t throwing out your gas stove, but the health risks are real. You should be aware and look for opportunities to make the switch to electric, if possible. We can make evidence-based decisions, even within the walls of our own home and outside of a pandemic, to live more healthy and prosperous lives.

Love, YLE, Dr. Levy, and Luis

Dr. Jon Levy is Professor and Chair of the Department of Environmental Health at Boston University School of Public Health, and he has published on indoor exposures from gas stoves for many years.

Luis Melecio-Zambrano is a science journalist and Masters student at the University of California Science Communication Program. They tell stories at the intersection of science and society. You can find their work at luismelecio-zambrano.mypixieset.com.

“Your Local Epidemiologist (YLE)” is written by Dr. Katelyn Jetelina, MPH PhD—an epidemiologist, data scientist, wife, and mom of two little girls. During the day she works at a nonpartisan health policy think tank and is a senior scientific consultant to a number of organizations, including the CDC. At night she writes this newsletter. Her main goal is to “translate” the ever-evolving public health science so that people will be well equipped to make evidence-based decisions. This newsletter is free thanks to the generous support of fellow YLE community members. To support this effort, subscribe below:

Katelyn, I regard you as a national treasure and a personal one, since I rely on you above all other sources for guidance for me and my family in coping with covid. Among the things I prize about YLE are the clarity with which you present abstruse data and also the objectivity. In our painfully polarized moment, it is not only refreshing but also reassuring to find presentation of information free of any hint of a political agenda. It pains me that this post, obviously written mostly by your partners, has a different tone. The title refers to the "culture war," and the tone and substance of the whole thing suggests a thrust from one side in that war. I wish you would avoid partnering with others who may be credentialed but lack your exemplary objectivity. Love you, too,

Thank you for this info. We have a gas fireplace that looks like a wood burning stove and run it for several hours a day during winter. Is this also a cause for concern?