Five billion dollars was just allocated to Operation Next Gen with one goal: speed the creation of next-generation COVID-19 vaccines and therapies, including nasal (mucosal) vaccines. I advocated for this at the White House, but it’s going to be a hard road. Here’s why.

What are mucosal vaccines?

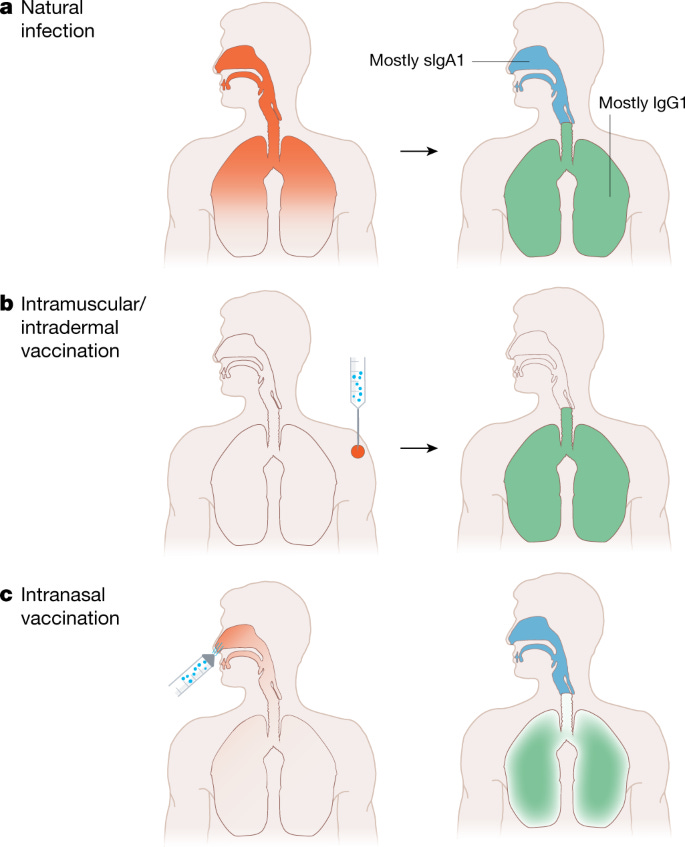

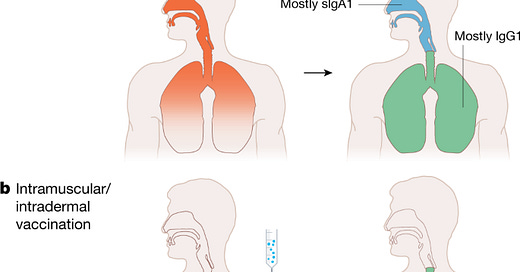

Mucosal vaccines, like ones administered in the nose, stimulate an immune response at the same portal the virus uses to enter our body—the upper respiratory tract (nose, tonsils, etc.). In theory, this would make them better at reducing transmission and preventing infections than a vaccine that is injected.

Sounds great, right? Yes. But there are some major scientific barriers that we need to overcome before we all get a nasal COVID-19 vaccine.

In short, it’s very difficult to make a mucosal vaccine that achieves the necessary balance between safety and efficacy. There is a barrier at each step of the process.

Challenge #1: Stimulating the immune system

The entry point of our body (i.e. mucosal surfaces) responds differently to stimuli than the body does to internal threats (i.e. injection vaccine). This is because the default response at our entry point is tolerance. We come into contact with harmless things at our mucosal surfaces all the time, like dust or food, and so the threshold for an immune response is higher.

There are a few ways scientists have been working around this:

Higher dose. The immune system needs to be provoked more, which means you need a higher a dose than with an injected vaccine.

Live virus vaccines. The only nasal vaccines we have right now are live virus vaccines (think FluMist). They work because they’re annoying enough to the immune system to provoke a response. But, SARS-CoV-2 is so skilled at mutating that there’s a risk a live virus vaccine could start to circulate and create variants.

Adjuvants. Some vaccines use adjuvants—ingredients that help stimulate the immune system. But we don’t have established adjuvants for mucosal vaccines. Scientists once produced an adjuvanted mucosal flu vaccine, but it was quickly withdrawn because it (rarely) caused Bell’s palsy.

“Prime and pull.” This is a newer approach—to use a nasal vaccine as a booster. This lets you “pull in” the memory response to the nose, which has been “primed” by the first dose of an injection. However, a vaccine that works like this has never been used in humans.

Challenge #2: Side effects

Even if we figure out how to stimulate the immune system, we need to account for inflammation. Think about what can happen with your arm after you get a vaccine (heat, swelling, pain). It might be more serious if that were to happen in your airway.

Challenge #3: Measuring effectiveness

It’s much harder to assess effectiveness:

Lab: Neutralizing antibodies, like we used with mRNA vaccines, are low-hanging fruit, but a separate set of lab tests are needed to analyze them in the mucosae, and the levels needed for protection aren’t well known. Not to mention the can of worms of T cell measurement.

Clinical trials. It’s even harder to assess effectiveness in a clinical trial given the underlying motivation to reduce transmission. This is challenging to test on multiple levels (recruiting participants, durability of protection, ethics).

Challenge #4: Proving additional benefit

Does a nasal vaccine meaningfully add to the landscape of protection? Especially in a world where many have been infected with SARS-CoV-2 (and so have some mucosal immunity).

The obvious counterpoint here would that be children who have yet to be infected might uniquely benefit from a mucosal vaccine, but it is possible they might benefit just as much from an injection vaccine.

Challenge #5: Scientific disagreement

Proponents of mucosal vaccines argue that IgA—the class of antibody most abundant on the mucous membranes—is important because it forms complex structures that bind to escape variants better than IgG (the major antibody in the blood). This means it could better protect against infection.

Skeptics raise an important counterargument, though. Roughly 1 in 500 people have a IgA deficiency. This is the most common immunodeficiency known, and the majority of people have no health problems from it- which argues against IgA in general being important for protection. In contrast, a deficiency of IgG generally requires antibody replacement therapy and is a severe condition. IgG antibodies also tend to last longer than IgA, challenging the prospects of durable protection from a mucosal vaccine.

The international community has mucosal vaccines, but…

There are options already out there. For example, India and China have nasal vaccines. However, their effect on transmission has yet to be shown (which itself may be a disappointing comment on their effectiveness given how long they have been around). Additionally, these vaccines have not been updated to contain Omicron spike proteins.

The vast majority of research is still in the animal phase, which shows promise, but we do not have any guarantee that the result will be the same in people.

We have done hard things

Anything that reduces the incidence of infections and curbs the spread of SARS-CoV-2 has the potential for massive public health benefit. If that can be translated to other infectious diseases, that would be superb.

Furthermore, a vaccine that can be administered without the need for a skilled medical professional is especially valuable in regions where such expertise may be sparse, as has been observed with polio eradication campaigns.

Bottom line

While a mucosal vaccine may help, there’s a lot of uncertainty. We shouldn’t oversell the potential but recognize the real challenges and cheer on the scientists who are trying to figure them out. Operation Next Gen should help move mountains, but time will tell.

Love, YLE and EN

In case you missed it:

“Your Local Epidemiologist (YLE)” is written by Dr. Katelyn Jetelina, MPH PhD—an epidemiologist, data scientist, wife, and mom of two little girls. During the day she works at a nonpartisan health policy think tank and is a senior scientific consultant to a number of organizations, including the CDC. At night she writes this newsletter. Her main goal is to “translate” the ever-evolving public health science so that people will be well equipped to make evidence-based decisions. This newsletter is free thanks to the generous support of fellow YLE community members. To support this effort, subscribe below.

SaNoTize is a measured nitric oxide spray application that has been clinically proven to kill all viruses in the nose. It was originally developed as a prophylactic against the flu. The tests showed that It kills ALL covid 19 virus in the nose within two minutes, and reduces viral load to a nearly undetectable amount in infected patients after two days. But don't take my word for it. Here is the result of the third stage trials in the LANCET. I use Enovid (its name in Israel) and it appears to work. I have traveled, gone to crowded venues with poor ventilation, (although I still wear a mask) and eaten in restaurants, with no infection. There are no contraindications with any medication.. It is not a drug. Nevertheless The CDC and Health Canada have not authorized it. Israel, Germany, India and Singapore DID in 2021, and it's available in any drugstore in those countries. The additional tests by Health Canada and CDC should be expedited. It's even more inexcusable in Canada, since it was developed in Vancouver. https://www.thelancet.com/journals/lansea/article/PIIS2772-3682(22)00046-4/fulltext

SaNoTize are developing a nasal flu vaccine. They should receive funding.

I also came to the comments today to share my experience with anti-viral nose sprays. I've been hoping for a post on these, but as mentioned by another commenter - they seem to risk falling into the 'misinformation' camp and so aren't talked about by many responsible COVID communicators. I have been using both Enovid and an iota-carrageenan spray for about a year now with good success. I am teacher in a primary school as is my husband and our two children attend the same school - so we have quite a bit of exposure!! During the winter and times of heavy transmission we all used the iota-carrageenan spray before school and Enovid after school. They both some decent studies with anti-viral success and seemed worth the try. We did not mask this year (though I do when working with actively sick kids and colleagues which happens a lot). We were sick significantly less than other students and staff. We also have travelled successfully (masking in airports/planes but not much elsewhere). We also managed one COVID case (picked up from a haircut in which my son forgot nose spray) without the rest of us getting sick (we did all use high-quality masks, lots of fresh air and isolation in addition to lots of nose spray).

For those in the EU, Enovid is now available through MaskWholesale.eu and is only 20 euros per bottle (still pricey but better than straight from the Sanotize website).