I’m fully vaccinated against measles. What should I know?

Can I transmit the virus? Does vaccine protection wane? Does my child get antibodies?

Measles continues to pepper the news:

A new outbreak in Georgia

Report last week of a 45-fold rise in measles in Europe

CDC released a national alert for physicians to keep an eye out for cases

I am getting a lot of questions! Here’s what you need to know if you’re fully vaccinated.

Can I get measles if I’m fully vaccinated?

The MMR vaccine works incredibly well—you’re 35 times less likely to get measles than someone with no immunity.

But nothing is perfect. A breakthrough case is rare but possible (3 out of 100 fully vaccinated people will get infected). The disease does tend to be milder.

We don’t know why there are breakthrough cases, but there are two possibilities:

Waning immunity (see more below); or

Vaccine didn’t work in the first place for whatever reason. 5% of people do not get protection after the first dose, but 95% of those will be fully protected after a second dose.

If I am exposed, can I transmit measles?

Transmission after vaccination, especially if you’re asymptomatic, is rare:

We see this in the lab data. A small study found no viral shedding among asymptomatic or mildly ill patients. But this is a very old study, and we need to replicate findings with more sensitive lab equipment.

We see this in the epidemiological data. While there are several studies showing spread among vaccinated people, especially after intense or prolonged exposure, the epidemiological implications don’t seem to be dramatic. In other words, cases don’t transmit enough to sustain outbreaks.

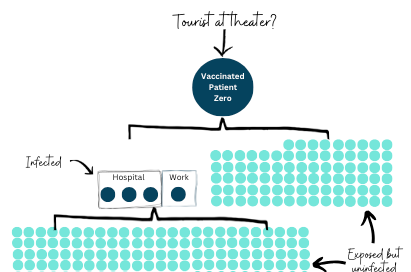

In 2011, there was a well-documented outbreak in New York. This was the first documented measles outbreak where the index case had two doses of MMR. Out of 88 close contacts, 4 got infected and had symptoms. Those who got infected had more than 200 contacts, and none got measles. (Note: We would expect ~90% to get infected if this population didn't have immunity.)

Why does the measles vaccine work better than the Covid-19 vaccine?

These are very different viruses:

Mutates differently. Measles is much more restricted in how it mutates compared to Covid-19. For example, new versions of measles don’t come out every few months to escape our immunity. The 1960 measles virus is largely the same today. (See this previous YLE post for more).

Infects differently. Measles is a lot slower at infection. It requires going deep into the body to start replicating. Because of this, the measles vaccine is much better at stopping transmission, as our body has much more time to control measles infection. This is different from Covid-19, which replicates on the surface of the nasal cavity very quickly. It’s hard for our cells to reach it in time to prevent replication.

If we are protected from measles for life, why are there booster rumors?

I think this happening for a few reasons:

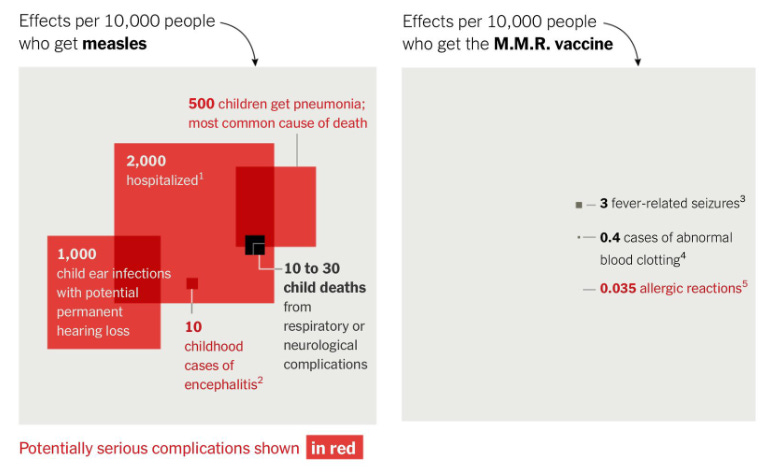

MMR combines protection for three diseases into one shot: Measles, mumps, and rubella. Each of these wanes at different rates, which is confusing:

Measles. Measles antibodies are incredibly durable (the most durable of the three) but wane over time. This isn’t too concerning because we have T cell protection, too. Studies that followed people for 17 years showed the vast majority (~91%) remained above the threshold needed for protection. What happens if they continue to wane? We are at the mercy of time, but currently, outbreaks continue to occur among unvaccinated people.

Mumps antibodies are also durable but wane faster than measles. Approximately 25% lose protection within 8 years and 50% within 19 years of vaccination. This is why some consider a third dose of MMR before kids go to college.

Rubella wanes, too, but you’re generally considered fully protected for life. Recent studies showed that the younger a person is, the quicker it wanes. This raises the question of whether women, especially those who get pregnant at an older age, need another booster.

Other countries are discussing the possibility of a measles booster, for example for health care workers in Korea. Studies show a booster provides benefits, but they are short-lived.

The guidance says if you were born before 1957, it is assumed you had measles and you’re fully protected. This group can probably skip getting MMR for measles protection unless other factors are at play (e.g., chemotherapy).

As vaccines have started eliminating diseases, people’s exposure to those diseases in the community has declined. This is good news, but it also means our immune systems have had less opportunity for boosting by asymptomatic infections (i.e., hybrid immunity). We don’t know the implications of this, but we are keeping a close eye on the data.

I hear measles infection-induced immunity is more durable than vaccine-induced immunity?

This is true. Infection-induced antibodies wane less quickly among adults and fetuses compared to vaccine-induced immunity.

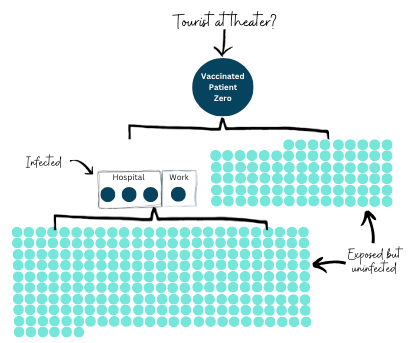

The problem is that an infection comes with many more risks than a vaccine. If I were to bet on it, I would rather have the odds on the right than left.

Are babies protected if their mom was fully vaccinated?

Anyone trying to conceive should have MMR titers checked, and if levels are low, MMR should be administered 28 or more days before conception.

The vast majority of moms transfer antibodies of all three—measles, mumps, and rubella—to fetuses. Once born, antibodies wane really quickly and are almost all gone at 6-12 months of age.

So why do we wait until 12 months to get children vaccinated?

We try to get to the sweet spot by balancing a few factors: maternal antibodies waning, maturity of the immune system, and the most common age of infection. For example, maternal antibodies can greatly reduce the infants response to the MMR vaccine. So we want to be sure these wane before getting a child vaccinated.

That said, if there is a measles outbreak, protection is needed ASAP for young children. Early vaccination is one provisional measure we can take.

Bottom line

If you’re fully vaccinated, you can be confident in your protection. We continue to follow the data, but failure to vaccinate still plays the biggest role in measles in the United States compared to vaccine failures.

Love, YLE

In case you missed it:

“Your Local Epidemiologist (YLE)” is written by Dr. Katelyn Jetelina, M.P.H. Ph.D.—an epidemiologist, wife, and mom of two little girls. During the day, she is a senior scientific consultant to several organizations, including CDC. At night, she writes this newsletter. Her main goal is to “translate” the ever-evolving public health world so that people will be well-equipped to make evidence-based decisions. This newsletter is free, thanks to the generous support of fellow YLE community members. To support this effort, subscribe below:

I recently asked for titers due to a close miss with a measles exposure in my local Costco and learned that while measles and rubella were still holding up great, my mumps immunity was at 0. I also learned I had no Hep B immunity so, presumably, I never got it. I missed the varicella vaccine due to its timing and my age, but figured that out in my mid-30s when my stepdaughter got shingles and gave me chickenpox. Fortunately, I knew what that was immediately and was able to get antivirals. I'm 48, to put that in age perspective. I have one Hep B remaining and then I will be all caught up.

I really feel that titers should be encouraged for everyone. No one wants to catch this stuff!

For those born before 1957, we assume they (we) all had measles as children. Did we all? Is there any evidence that people born before 1957 should be vaccinated or titers checked for previous disease?