Para leer la versión en español, pulse aquí.

Another familiar respiratory virus is back: influenza (otherwise known as the flu). Influenza circulated at historic lows last year. In fact, flu was the lowest it’s been since 1996 (when we first stated tracking the flu), presumably due to a change in social behaviors associated with the pandemic (i.e., mask wearing, hand washing, limited social gatherings, etc.).

But public health officials are increasingly concerned about the flu this year. On January 10, 2022, the World Health Organization asked national health authorities to monitor national trends and pay close attention to new cases and their subtypes. Globally, infections remain low, when compared to the competition of COVID-19 variants, but cases are expected to increase.

United States

Influenza is infamous for its variant diversity and ability to mutate at a rapid rate. Typically, influenza has two strains (A and B-, with multiple subtypes within each group) that circulate each year. We try our best to predict which subtype will circulate to prepare annual vaccines by relying on two things:

The previous 2-3 years of data and,

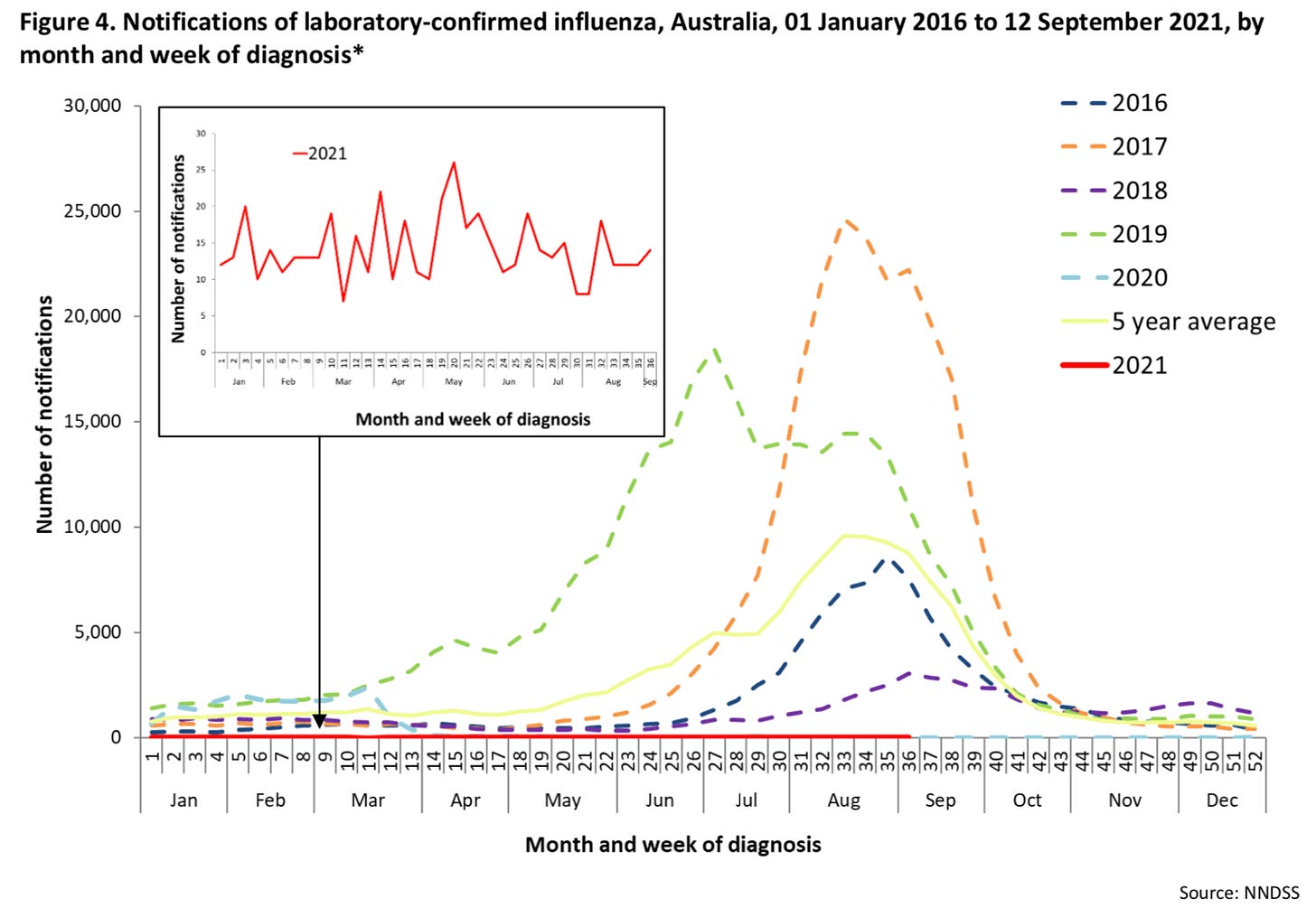

Trends in Southern Hemisphere countries like Australia, which experience the flu season before the U.S. The challenge this year, though, is that Australia didn’t have a flu season due to pandemic restrictions. (Here is a look at their 2021 flu season, or rather lack thereof).

But because influenza is zoonotic (comes from animals like birds and pigs), our vaccines don’t often achieve maximum efficacy like we’ve seen with COVID-19 vaccines thus far. The ability for influenza to infect animals causes the virus to mutate rapidly before entering the human population again.

Nonetheless, the CDC has reported Influenza A and B in the United States this year. Influenza A (H3N2) —informally known as swine flu— is by far the most prevalent. We know this because the CDC randomly tests flu specimens for the specific strain and their latest update found H3N2 accounted for more than 99% of specimens. Unfortunately, H3N2 is the most concerning strain since it’s been responsible for previous severe outbreaks in the U.S.

Cases and hospitalizations

Influenza is on the rise in the U.S. In the beginning of January, nearly every state in the U.S. was experiencing flu activity. Many states were reporting a high or very high level of flu cases, particularly in the South and East.

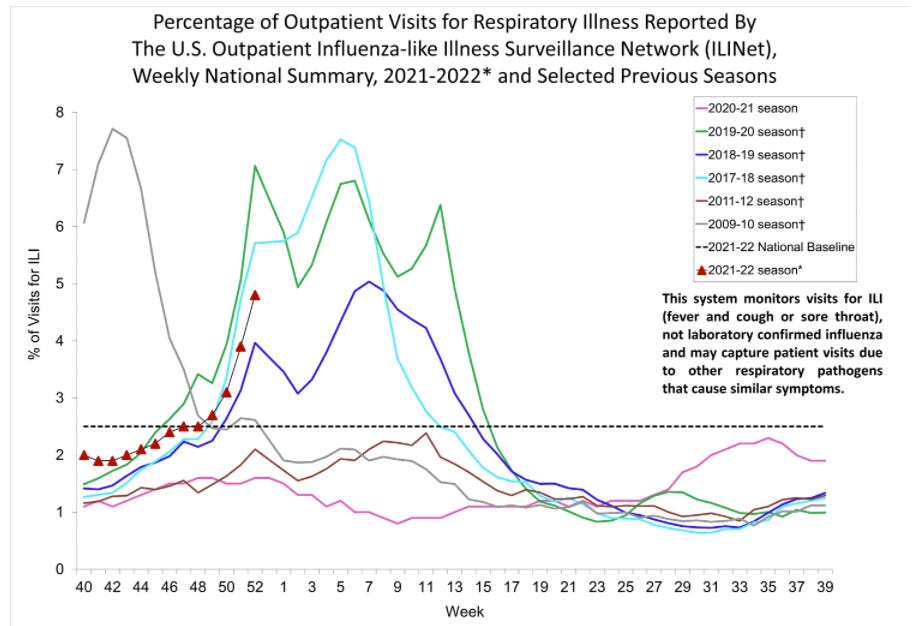

Unlike COVID19, positive influenza tests are not systematically reported. So, instead, we rely on outpatient healthcare visits with patients reporting respiratory-like illnesses such as fever, cough, and sore throat. Importantly, these are cases of “influenza-like illness (ILI)”, so not necessarily influenza. A lot of these could be COVID19 instead. Unfortunately, this is best indicator we have of community flu transmission trends.

ILI numbers are actively updated by the CDC and displayed in the figure below. This year (red triangles) it looks like ILI activity is back to “normal”— the trend is reflecting the 2017-2018 and 2019-2020 seasons. But again, I’m really not confident in this data, as this could be COVID-19, too.

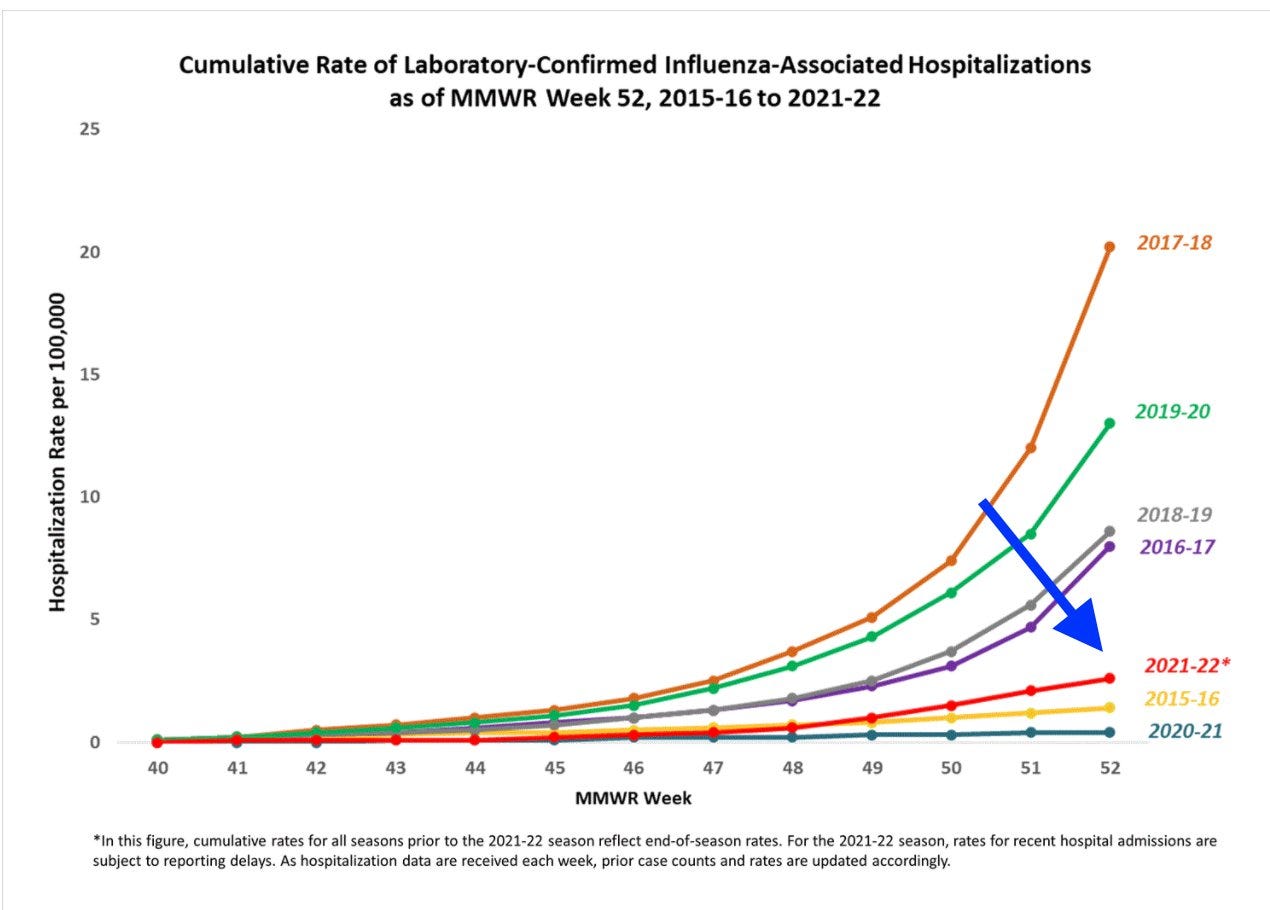

Hospitalizations show a little different story. Fortunately, the increase in influenza-associated hospitalizations is modest. On January 1, an average of 2.6 per 100,000 Americans had the flu. Compared to previous seasons, this year is tracking relatively low: The hospitalization rate isn’t nearly as severe as the 2017-2018 season, but looks to be more active than last year (2020-2021 season).

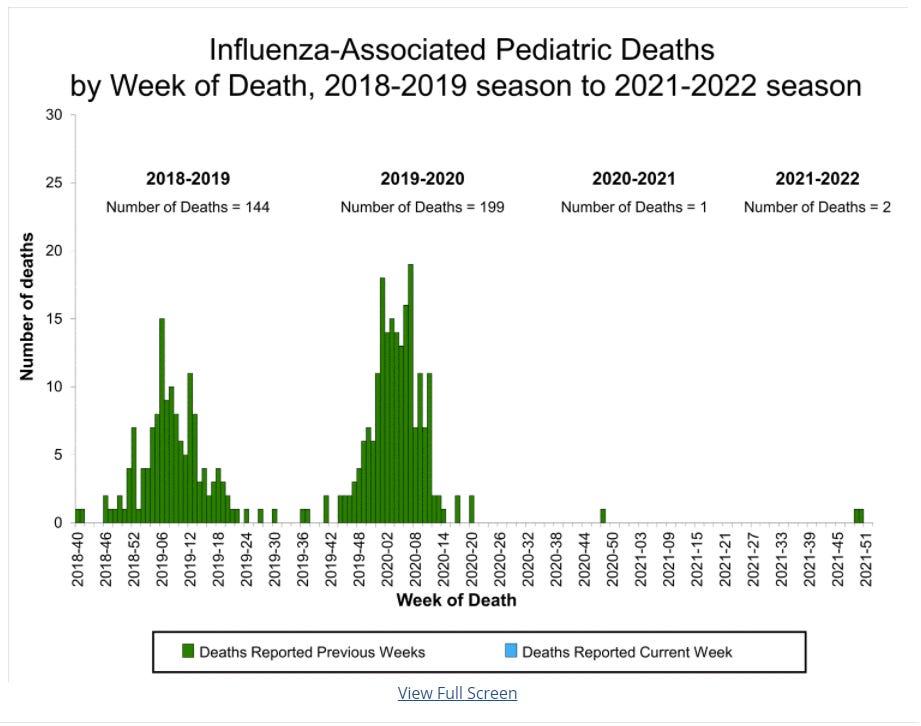

In December, the CDC reported the first two fatalities from the flu, who unfortunately were children. Last year we only saw one pediatric death during the entire flu season.

Vaccination coverage

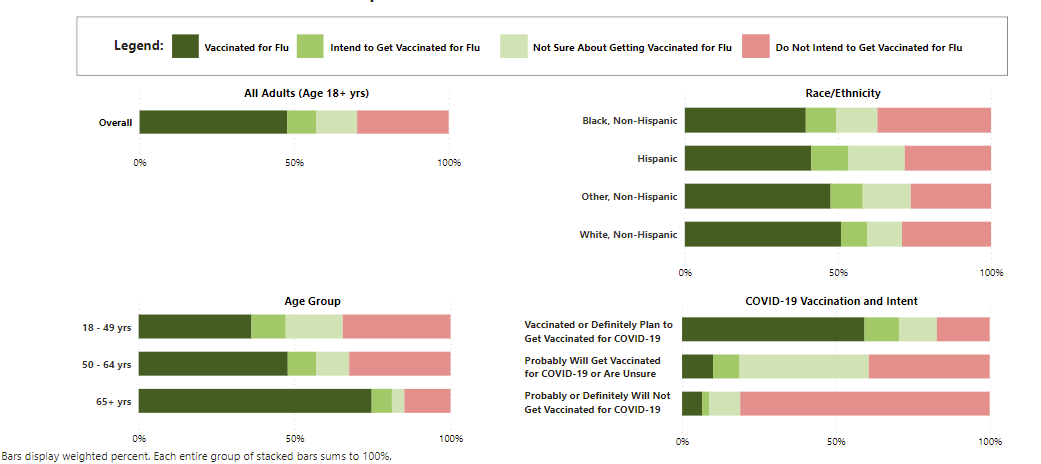

Americans notoriously skip the flu vaccine every year. As with the COVID19 vaccine, there is a lot of misinformation about the flu vaccine. (For the record, the flu vaccine does work; it does not give you the flu; and it is needed. See my previous post for more.) During the 2019-2020 flu season, 64% of kids and only 48% of adults were vaccinated for the flu. This year 47% of adults have the flu shot, and 10% more plan to get the vaccine soon. This is suboptimal coverage.

So, where’s the big flu wave?

Many epidemiologists, including myself, were expecting a big influenza wave this winter. First, there was little-to-no immunity from last year. Even though the virus changes a lot from year to year, immunity typically lasts about two-ish years. Second, we had an uncharacteristically big wave of RSV over the summer, which didn’t get us excited about the winter, when these viruses thrive.

But, the rate of influenza-like illnesses are about “normal” in the United States with corresponding low hospitalization rates. A severe flu year could still come, but we should have already seen its colors by now. So where is it? There are two circulating hypotheses:

Mitigation measures: Could this be due to COVID19 mitigation measures, like masks? Maybe. Yet anyone walking around in the South can tell you that public health mitigation measures (or lack thereof) certainly don’t explain it all.

Omicron surge: Interestingly, the WHO stated this could be due to the Omicron wave causing a suppressive effect on flu. They said: “With the sharp increases of omicron in many countries, it is not yet certain if the influenza activity trends will continue or come down again.”

We don’t have a good sense of the interaction of circulating respiratory pathogens. I’m hoping that when Omicron recedes, we won’t see increased influenza activity, especially since the more severe influenza strain is circulating. But we are keeping an eye on it. Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, influenza placed a large burden on our healthcare system. The CDC reports influenza was responsible for up to 41 million cases, 710,000 hospitalizations, and 52,000 deaths annually between 2010-2020. Influenza during the 2017-2018 year was particularly detrimental, contributing to an increase in excess deaths in the United States. To say the least, a “twin-demic” would be less than ideal, especially for our exhausted, depleted, and thin healthcare and public health workforce and infrastructure.

What is “Flurona”?

“Flurona” is a trending term on social media referencing individuals with a coinfection of influenza and COVID-19. But this term makes it sound like the flu and COVID-19 mutated to create a super virus. This is NOT what happened. In fact, health professionals have warned not to use this term.

Coinfection of COVID-19 and influenza is not a new phenomenon and has been around since the beginning of the pandemic. In fact, a recent study summarized 12 studies conducted around the world with 9,498 patients, to evaluate the risk effects of SARS-CoV-2 and influenza coinfection. Most of the studies were conducted in China, and among these, coinfection did not increase mortality. However, among the studies conducted outside of China, coinfection significantly increased mortality by 56%. The authors found that other critical outcomes, like hospitalization, were not impacted by coinfection.

Anyone can get a coinfection. People at high risk for severe outcomes, though, are those that are older (aged 65 and older), have a chronic medical condition (such as chronic cardiac, pulmonary, renal, neurologic, liver, hematologic, and metabolic illnesses), or have an immunosuppressive condition (such as HIV/AIDS, individuals taking chemotherapy or steroids, or malignancies).

Bottom line

Get vaccinated for both viruses. It’s not too late. Wash your hands frequently and wear a mask to protect yourself from COVID-19 and the flu. Be aware that more severe flu strains are beginning to circulate and the co-circulation of the two viruses could have consequences for individuals, communities, and healthcare systems.

Love, YLE and Lauren Leining

Lauren Leining, MPH is one of our PhD candidates in Epidemiology at the UTHealth Science Center in Houston, TX. Her academic interests include infectious diseases, parasitology, emergency response, and health policy. She graciously offered to keep the YLE community updated on other infectious diseases around the world – a topic the YLE community has voiced considerable interest in. Follow her on Twitter @LaurenLeining.

“Your Local Epidemiologist (YLE)” is written by Dr. Katelyn Jetelina, MPH PhD— an epidemiologist, biostatistician, professor, researcher, wife, and mom of two little girls. During the day she has a research lab and teaches graduate-level courses, but at night she writes this newsletter. Her main goal is to “translate” the ever-evolving public health science so that people will be well equipped to make evidence-based decisions. This newsletter is free thanks to the generous support of fellow YLE community members. To support the effort, please subscribe here:

What is your opinion about the optimal timing of a flu vaccination? I have read in reliable-sounding places that the protective effect of a flu vaccination declines by about 10% per month. If that's true, isn't the best approach to wait until flu levels begin to rise in your area and then go get the shot? Health professionals in the press began pushing the public to get the shot around the beginning of Sept. But in most of the US there was almost no flu around at point. I watched the CDC info about flu activity for my state, and once it started creeping up towards the top of the green "minimal" category, in early December I went for a flu shot. Is this strategy OK? I was thinking that maybe the reason health professionals were hectoring us in Sept. to get a flu shot was that they figured it would take 2 or 3 months of hectoring to get the public to go get the shot.

Are there any different types of flu vaccines in the works?

I typically end up skipping as I have a verified allergy to an ingredient in the vaccine, try several pharmacies, and can’t find it without. I was pleased to not have this issue with my COVID vaccination. I remember reading that Moderna was working on a combo vaccine but wonder if it would then have this same drawback.

Meanwhile, I have lots of very fashionable masks that I am happy to wear indoors, even though in Florida, it seems like most customers don't now. Only the workers. Sad.