Make America Healthy Again?

RFK, Jr.'s plan sounds catchy, but won’t move the national needle

YLE is taking our own advice by being upfront: This post is based on data and our personal values system that highly prioritizes public health. Our goal here is to lay out, to the best of our ability, what a policy would mean based on objective data and personal experiences watching how public health works in real life.

A catchy slogan from RFK, Jr. has been unearthed in anticipation of the elections: Make America Healthy Again. As people who have dedicated their careers to protecting and improving the health of populations, we absolutely agree that we need to work towards making America healthier!

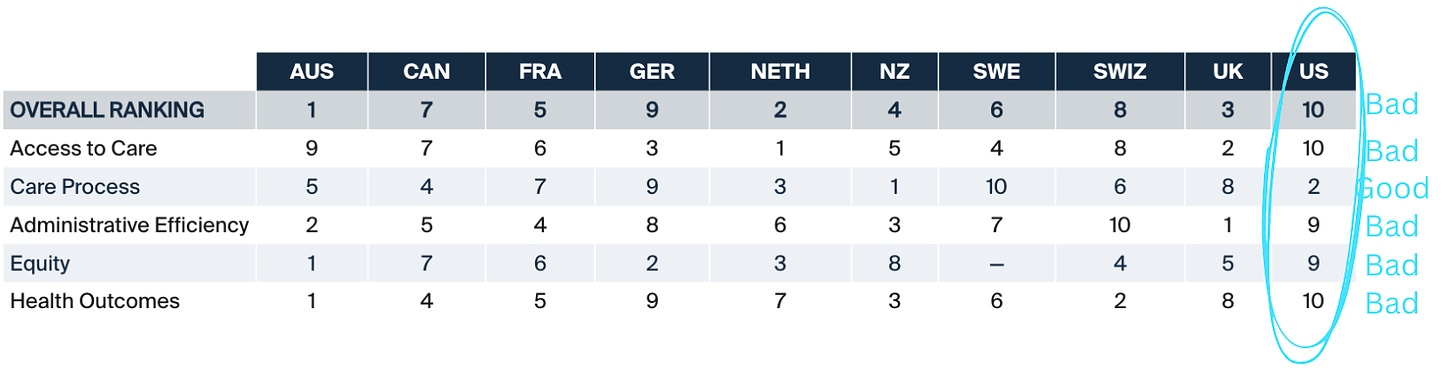

After all, America has room for improvement: We live the shortest lives, have the most avoidable deaths, have worse healthcare access, and have worse health compared to other developed countries.

The first step is to accurately identify what is causing us to be unhealthy and fix that. We won’t make substantial progress if we chase after falsehoods.

But the big MAHA talking points—organic food and pesticides, alternative medicine, and removing pharmaceutical hold—often lack specificity, are riddled with falsehoods, and widen the risk perception gap—focusing on relatively minor issues while overlooking more significant threats that shape our health.

In addition, the key players behind the proposal have a horrible record on evidence-based policies: consistently discouraging routine vaccines, touting the health benefits of unproven and potentially dangerous remedies such as raw milk, and promoting supplements for profit instead of evidence-based treatments.

To achieve a healthier tomorrow, core values of public health can help with:

The pursuit of accurate information

The pursuit of reducing preventable diseases and hazards,

The protection of everyone’s health

The pursuit of scientific reality

Creating a better world means first clearly seeing the world as it is.

One of the most dangerous aspects of the MAHA campaign is mixing reasonable statements with outright falsehoods. This combination makes it extremely difficult for the general public to distinguish fact from fiction and determine where we can get the most bang for our buck.

Some examples include:

“Medicaid should pay for 3 organic meals daily for every American.” Access to nutritional food is a huge problem in the U.S.—this part is true. However, there is no strong evidence to date that organic food is nutritionally superior. And organic food can be unhealthy — you can make ice cream organic, but that doesn’t make it good for you. We should prioritize increasing access to nutrient-dense foods—whether fresh, frozen, or canned—regardless of whether they’re organically or conventionally grown.

“Embrace alternative medicine.” Many alternative medical therapies simply do not work and, more dangerously, may discourage people from seeking tested therapies. Instead, addressing our primary care crisis would have a much bigger impact on our nation’s health. Primary care matters — it’s associated with decreased mortality and chronic diseases, like cardiovascular disease.

“Get toxic residues and pesticide residues out of our foods.” Residues on fruits and vegetables are extremely limited. Simple actions, like washing with running water, effectively remove residues. A push towards the European model is less about actual exposure levels and more about theoretical harm. Organic farming also uses pesticides, just different ones that aren’t necessarily safer for humans or the environment. And they usually need more to be as effective.

“Prohibit members of the U.S. Department of Agriculture Advisory Committee from making money from food or drug companies.” While avoiding conflicts of interest is important, this proposal creates a false dichotomy between expertise and industry and excludes valuable knowledge and expertise. For instance, despite industry connections through his research, Dr. Walter Willett, a professor at Harvard, has shaped public health guidance on the role of healthy fats and plant-based diets. A more balanced approach involves transparent disclosure and management of potential conflict, similar to models used by the NIH and FDA, distinguishing between conflicts of interest that are handled appropriately versus genuine corruption.

The pursuit of reducing preventable diseases and hazard

Freedom can mean very different things to different people. On the one hand, it can mean “do what we wish,” but on the other, it’s a “pursuit of living free from preventable hazard and disease.” In the United States, our culture balances the two.

Access to medical care helps Americans live free, healthy lives—to live, prosper, and contribute to society. However, Americans face more barriers to accessing and affording healthcare than their counterparts. One in four Americans has trouble paying their medical bills, which leads to delayed care until many conditions become emergencies, increasing costs and resulting in poorer health.

MAHA suggests using Medicaid to pay for organic food and gym memberships. It’s unclear if they intend to cut insurance coverage, but given budgetary constraints and the high cost of organic food, this may be a consequence. This would be a big problem: Diet and exercise are very important but cannot solve all medical problems. A delivery of organic produce is no replacement for access to healthcare.

Moreover, MAHA calls for “cleaning up the public health agencies.” This is like trimming the fire department even though more houses are catching fire, as public health’s DNA is prevention. While we agree that federal agencies need to be more nimble, flexible, and responsive to the needs on the ground, proposals like MAHA overlook the existing challenges in public health infrastructure:

MAHA calls for decentralizing public health. But public health is already decentralized. The power of public health is already given to the States, which makes sense since public health is local. However, under this proposal state funding diminishes; only a skeleton remains until the next emergency. How can we focus on prevention—including through efforts like access to mental health, addressing food deserts, and preventing teen pregnancy—when we have barely enough resources to put out fires?

MAHA calls for weakening CDC through restructuring. CDC, our national public health entity, holds the State public health ligaments together through data and guidance. If this weakens even further, the whole system breaks. Adding more institutions (like proposals to split up the CDC) adds to bureaucracy. Institutions need to be cohesive with sufficient, stable, and efficient funding if we want institutions to be more nimble.

“Replace industry-capped officials with honest public health servants.” This implies that public health agencies are completely controlled by pharma, which is simply false. It also implies that public health employees are not honest servants. Public health professionals don’t get into this profession for the money (there’s not much); we are here for the mission.

Protect the health of everyone

Public health’s core mission is to improve population health. Part of this strategy involves addressing the needs of the most vulnerable.

For example, consider routine vaccination mandates. Children <1 year are the most vulnerable to measles, and pregnant women are the most vulnerable to rubella but are not eligible for vaccinations. So, everyone else gets MMR to protect high-risk people through herd immunity (and everyone else.). (Note: RFK, Jr. has spent the past two decades eroding vaccine trust that has done irrevocable damage.)

Large-scale, evidence-based interventions help reduce chronic conditions, too. For example:

Instead of advocating for meditation alone, coordination between mental health and primary health care improves mental health. Parental leave also helps families that can barely make ends meet, reducing stress.

Instead of focusing on pesticides’ small impact, policies to reduce environmental pollution would protect vulnerable communities from industrial exposures. For example, low-income groups continue to be exposed to higher levels of dangerous fine particulate air pollution than higher-income groups.

Rather than vilifying non-organic items, we should promote policies that improve access to nutrient-dense, affordable options in food deserts.

Bottom line

Everyone agrees we need to build a healthier America. Many of MAHA’s vague proposals won’t substantially improve it; in some cases, it will move us backward. National progress comes from policies that lead with evidence, improve access to quality healthcare, and invest in prevention and infrastructure.

Let's focus on what truly works, not what merely sounds catchy. That’s how we'll build a healthier, freer America for all.

“Your Local Epidemiologist (YLE)” is founded and operated by Dr. Katelyn Jetelina, MPH PhD—an epidemiologist, wife, and mom of two little girls. The main goal of this newsletter is to “translate” the ever-evolving public health science so that people will be well-equipped to make evidence-based decisions. This newsletter is free to everyone, thanks to the generous support of fellow YLE community members. To support this effort, subscribe below:

Unbiased Science is a science communication organization that provides practical and accessible health and science information to the public. It is led by Dr. Jessica Steier, a public health scientist with expertise in policy evaluation.

Kristen Panthagani, MD, PhD, is a resident physician and Yale Emergency Scholar, completing a combined Emergency Medicine residency and research fellowship focusing on health literacy and communication. In her free time, she is the creator of the medical blog You Can Know Things and author of YLE’s section on Health (Mis)communication. You can find her on Threads, Instagram, or subscribe to her website here. Views expressed belong to KP, not her employer.

In response to, "One in four Americans has trouble paying their medical bills, which leads to delayed care until many conditions become emergencies, increasing costs and resulting in poorer health": Or resulting in death. I just had a friend die because she was afraid to go to the hospital due to a prior hospital bill she was unable to pay. She had contracted COVID and had underlying congestive heart failure and diabetes, as well as being 71 years old. I noticed her having trouble breathing and checked her oxygen saturation with a pulse oximeter. It was at 85, and I told her she needed to go to the hospital. She might well have lived if she hadn't been afraid to go due to trouble paying her medical bills.

As a clinical social worker living in rural Maine and in my personal life, I have a fair amount of contact with people who have very little trust in the Medical/pharmaceutical/governmental complex Parentheses sometimes of good reason). I struggle with feeling helpless in this crazy, fractured time, but try to arm myself with accurate, unbiased information presented in a thoughtful way that stays clear of judgment and/or the culture wars. This is where YLE comes in. What you write about and how you present it helps me to become more informed and to stay sane. I especially appreciate it when you take on currently popular beliefs head on, as you did in this article, one idea at a time. Thank you for being a fount of knowledge and a voice of reason in a time when neither knowledge or reason is especially popular. It matters, and I am very grateful.