Science, Policy, and Values

Be clear on where the data ends and opinions begin

This is our final post in this mini-series looking back at the public health communication around the COVID vaccines, why trust was lost, and where communication broke down. Catch up on the first three posts: misinformation versus miscommunication, expectation management, and why shaming ‘antivaxxers’ backfires.

If you talk to people about why they lost trust in public health during the pandemic, there is one topic that comes up over and over again: mandates. For many, the choice wasn’t simply get vaccinated or risk getting sick, it was get vaccinated or lose your job.

Many people’s core values—like liberty and autonomy—were directly under threat, so they pushed back against the scientific information. They didn’t want a new vaccine to be forced upon them, so they looked for reasons to say the vaccines didn’t work or even worse, were dangerous and killing thousands of people (a rumor one third of Americans believe today). Disagreement with policy decisions (vaccine mandates) and disagreement with the data underlying them (vaccine effectiveness and safety) were conflated.

Unfortunately, public health often made the same mistake in the opposite direction.

Because of the strong evidence that more vaccinations would save lives (and that mandates would increase vaccination rates and reduce the significant strain on healthcare systems), mandates were framed as the objectively correct scientific choice, and those disagreeing were labeled “anti-science.”

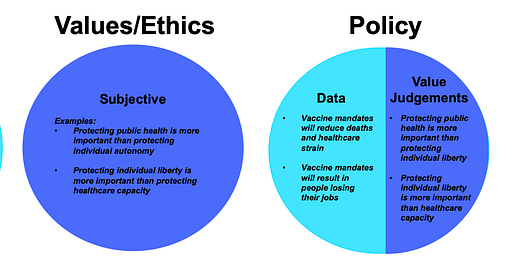

But policy decisions weren’t just about the data, which was in flux. There were values at play on this side, too. Deciding how to balance the trade-off between protecting the vulnerable and infringing on individual autonomy is always a judgment call, not a scientific “fact.”

Problem #1: Confusing data and values

The authority of science comes from its objectivity. When a study is designed well, the results do not depend on the scientists who ran the experiment. It’s reproducible—a Democrat, Republican, Christian, atheist, conservative, or liberal could all run the same experiment, and they would get the same answer.

While in practice science is imperfect and messy, when done well, it is the closest thing we have to objective truth about the natural world. This is why science carries so much authority—it is not just a matter of opinion, but as close to objective reality as possible.

Policy is much trickier. As UC Berkley’s Science 101 article states: “Science doesn’t tell you how to use scientific knowledge.” Science-informed policy, while based on data, is not purely objective—it is a messy combination of objective data and subjective values, informed by data as well as ethics, priorities, resources, and culture. Two people can agree on the data, but still disagree on what decisions to make based on that data, because they have different worldviews and value systems influencing decisions.

Conflating science and science-informed policy erodes trust

When value judgments—like “promoting public health is more important than protecting individual liberty”—are presented as an objective truth like science itself, trust in “science” takes a big hit. Unfortunately, this happened frequently during the pandemic. Policy decisions like mask mandates and vaccine mandates were presented as the scientifically “correct” choice, without acknowledging tradeoffs (economic burden, infringement on personal autonomy) and the value judgments that ultimately drove decision-making (collective good is more important than individualism).

The scientific method cannot answer value questions like which is more important, life or liberty? There is no experiment that will reproducibly and objectively answer this question. If we say “science” has given us an answer, people will rightfully call BS.

If scientists mix their values, ethics, and opinions into the data and call it all “science,” the public will view science as a matter of opinion. This leads people to reject things science can answer—like data on how well the vaccines are working.

Problem #2: The science changed

The virus mutated, and the science was in flux. Waning vaccine immunity and the unexpected Thanksgiving arrival of Omicron meant the data driving decisions to implement national vaccine mandates in September 2021 was out of date just a few short months later.

Omicron caught everyone off guard, and it’s not reasonable to expect public health to predict the path of an unpredictable pandemic. Public health decisions have to be made in real time, with the data at hand. At the same time, waning immunity and the extreme contagiousness of Omicron meant the benefits of vaccination changed after just a few months, altering the benefit/tradeoff calculus underpinning the mandates. The vaccines were still saving thousands of lives, but weren’t quite as good as the initial data showed, especially in reducing risk of infection.

How to do better next time

Were vaccine mandates the right decision? The wrong decision? Different people will have different answers to that question—depending on how they weigh lives saved, lost jobs, health care capacity, government authority, trust in science, and many other complicated factors.

Public health lives at the intersection of science and policy, and no policy decision is going to please everyone. Maintaining “perfect” trust is not a goal we can reach, and incorporating values is critical for guiding decision-making that will impact people’s lives. Moving forward, however, we can change how we talk about those decisions and avoid communication errors that unnecessarily erode trust:

Be clear what’s data and what’s values. Scientists get to have opinions and values, and get to express them. This is especially true for public health. BUT. It is critical we are very clear about what we’re doing: when we are communicating objective facts, and when we are layering our values on top of those facts. For those who are doing the important work of advocacy, be clear where the data ends and opinions begin.

Lives matter, and autonomy matters. Life and liberty are both core values that the vast majority of Americans hold dear. Essentially no one was questioning that these values are important. But when do we sacrifice one for the other? That’s where things get trickier, and different value systems will come up with different answers.

We need trusted messengers who focus on the data. Many people want “just the facts,” without values or political bent layered on top. There are a paucity of sources that provide this, and we need more people from diverse backgrounds to fill this need.

When it comes to differences in values, have humility. We all think our value systems are the correct ones, but there is no scientific test to validate this. While we can make ethical arguments to defend our views, this is separate from scientific fact.

Communicate scientific uncertainty. Many people expect established “textbook” facts, not emerging data and scientific flux. We can’t expect scientists to be clairvoyant, but we can do our best to communicate uncertainty in a rapidly evolving situation.

Bottom line

Science-informed policy is incredibly important. But, we need to be clear what is data, and when our values are layered on top of that data. The blurring of the lines damages trust in science. When we call our opinions “science,” the public will view overwhelming scientific consensus as a matter of opinion.

Sincerely, KP

Kristen Panthagani, MD, PhD, is a resident physician and Yale Emergency Scholar, completing a combined Emergency Medicine residency and research fellowship focusing on health literacy and communication. In her free time, she is the creator of the medical blog You Can Know Things and author of YLE’s section on Health (Mis)communication. You can find her on Threads, Instagram, or subscribe to her website here. Views expressed belong to KP, not her employer.

“Your Local Epidemiologist (YLE)” is a newsletter with one purpose: to “translate” the ever-evolving public health science so that people will be well-equipped to make evidence-based decisions. This newsletter is free to everyone, thanks to the generous support of fellow YLE community members. To support this effort, subscribe below:

Vaccine mandates have been upheld as Constitutional since 1905

The Supreme Court explicitly upheld vaccine mandates against deadly diseases in Jacobson v Massachusetts where it explained: "the rights of the individual in respect of his liberty may at times, under the pressure of great dangers, be subjected to such restraint, to be enforced by reasonable regulations, as the safety of the general public may demand." We live in a country of ordered liberty, not individual autonomy that paves the way to the deaths of others. In short, it is not the right of every American citizen to catch and transmit a potentially fatal infection." Public health and safety supercedes individual rights every time.

The anti-science and anti-vaxxer movement existed long before Covid and those opposed to mandates were already not getting vaccinated.

We were never going to reach these people.

This is an important and coherent analysis. Yet, speaking as an 82 year old family doc and public health practitioner, you have missed an very important factor: When you write, "When value judgments—like “promoting public health is more important than protecting individual liberty”—are presented as an objective truth like science itself, trust in “science” takes a big hit," you have overlooked the massive change in values in the public square over the past 60 years (which you probably have not personally experienced). You are not alone. This caught the public health establishment unawares in 2020.

Coping with the Great Depression and WW II, required values of cooperation, communal and personal responsibility and "neighborliness." Coasting on the era of prosperity starting in the 1960s (and magnified by persistent failure of government programs to solve major problems while promoting unnecessary wars) the values of individual freedom and liberty came to predominate over the past 60 years. This loss of "social capital" was well described and predicted in Robert Putnam's BOWLING ALONE, published in 2000.

In the 1950s everyone praised the development of polio vaccines and eagerly stood in line to get them. Then came MMR, etc and school mandates and the public praised and adopted the scientific successes. Mandate or not they wanted scientifically produced protection for themselves and their children. (Yes there were similar, fabulated right wing protests about fluoridation, but it was a fringe movement.)

So there is a deeper aspect to this discussion which is based on an understanding of the atrophy of social capital in the United States. This is important because this not only impacted public health strategies, it is the same phenomenon that is fueling the current turmoil feeding the MAGA movement and DJT.