Monkeypox is not a Public Health Emergency of International Concern, but perhaps it should be

Over the weekend, the WHO did not declare Monkeypox (MPX) as a Public Health Emergency of International Concern (PHEIC). This was a big surprise. Cases are increasing and MPX is quickly establishing itself across the globe.

Public Health Emergency of International Concern (PHEIC)

The WHO Emergency Committee is charged with discussing whether a health emergency qualifies as a PHEIC. A PHEIC is a key legal mechanism within global health security. As scientist BK Titanji summarized:

PHEIC declarations can: Mobilize international coordination, streamline funding and accelerate the advancement of the development of vaccines, therapeutics and diagnostics under emergency use authorization. This will hopefully catalyse timely evidence-based action, to limit the public health + societal impacts of emerging and re-emerging disease risks.

Declaring a PHEIC is not the same thing as declaring a pandemic. “Pandemic” is rhetoric that governments use as a communication tool. In theory, PHEIC comes far before a pandemic.

The declaration of PHEIC is based on three criteria:

Is it unusual and unexpected?

Is there potential for cross-border transmission?

Does it require a coordinated international response?

Notice the above does not include factors like location, economic or political tensions, severity of infection or case fatality rate, transmissibility, or healthcare capacity. Unfortunately, previous PHEIC declarations have been controversial because they have considered other factors. For example, some questioned whether Zika didn’t pass the test due to the politics of Brazil hosting of the 2016 Olympic Games.

Since the PHEIC mechanism started in 2005, a PHEIC has been declared six times: H1N1 (2009), Ebola in West Africa (2013-2015), Ebola in DRC (2018-2020), Polio (2014-present), Zika (2016), and COVID-19 (2020-present). The Emergency Committee met about three others events (MERS in 2013; yellow fever in 2016; and Ebola in 2018) but ultimately didn’t declare PHEIC. To date, all PHEICs have been centered around viral infections, but they do not have to be.

The committee met last Thursday and Friday. Over the weekend, the WHO ultimately decided not to declare MPX a PHEIC. This was a big surprise. MPX checks off all three boxes above. Perhaps MPX is not “unusual” because it’s been endemic in Africa for decades, but it is spreading very differently than before. Ultimately, the committee said it will reassess if one of many serious things happen, including:

Cases among vulnerable groups (pregnant women, children, immunocompromised)

Evidence of increase in severity

Reverse spillover to animals

Resistance of antivirals

Increased transmissibility

In my opinion, these are beyond the scope of the original criteria. Wouldn’t we want a PHEIC to prevent these terrible things from happening? We must get out of this reactive response mode. The window to stop this virus is closing. As Professor Michael Worobey said:

This is like deciding to snooze for an hour when the smoke alarm goes off to be good and sure it's a real fire. Time to realize it's smart to get out of bed even for false alarms now & then.

The WHO does have a history of being conservative. Hesitating to declare a PHEIC for fear of being accused of over-reacting has occurred in the past, like with SARS-CoV-2 and Ebola. Although not related to the WHO decision, there is growing skepticism whether declaring MPX a PHEIC will actually do anything. Unfortunately, problems have arisen during previous emergencies questioning the power of a PHEIC (and the power of the WHO).

It will be interesting to watch how this unfolds in coming months.

MPX State of Affairs

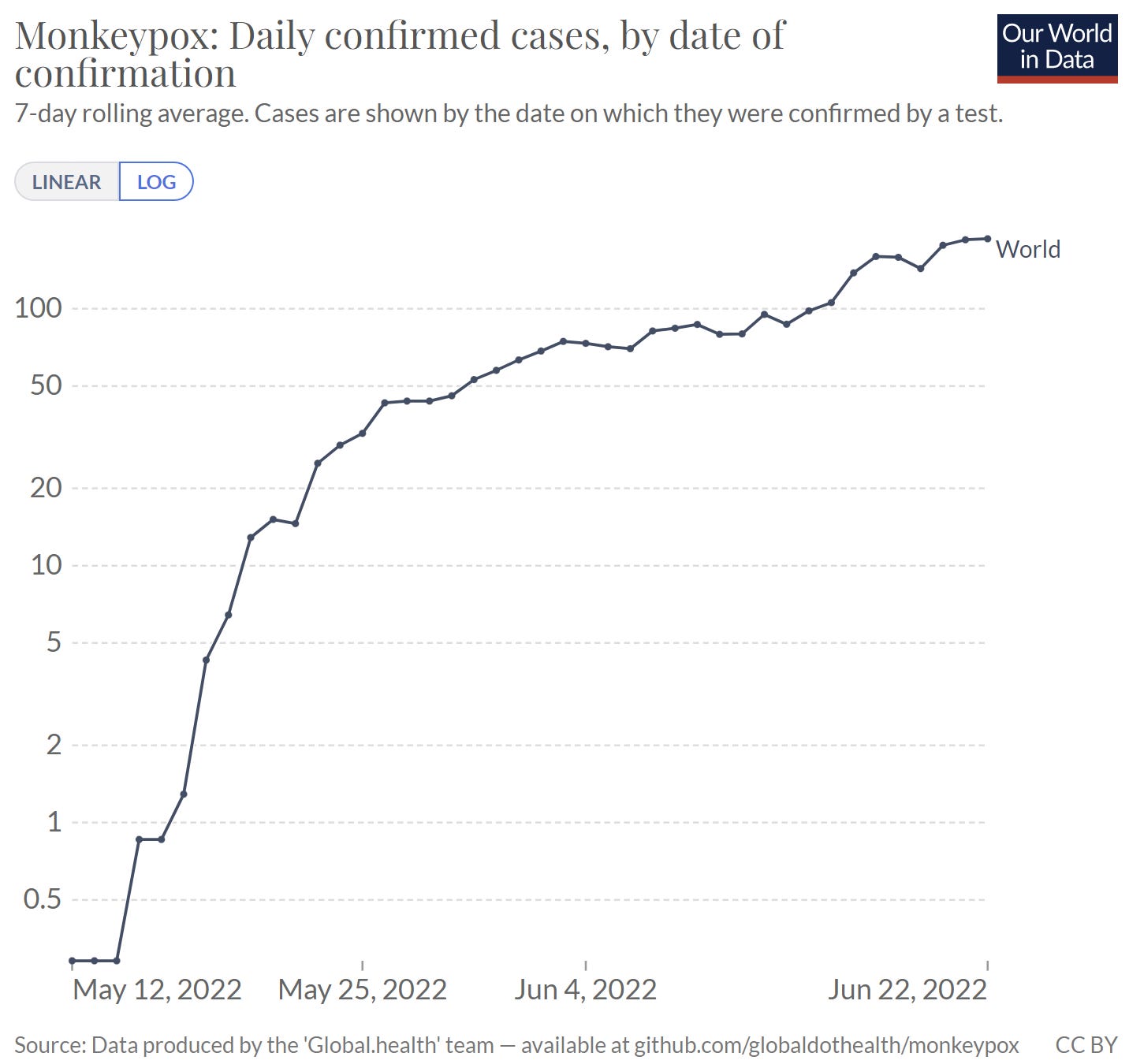

According to the latest count, 4,229 confirmed and suspected cases have been reported across 67 countries and 6 WHO regions. The graph below shows acceleration (note this is a log graph). There was initial, fast acceleration due to “bulk reporting” — as awareness increased, identification also increased. The acceleration slowed down as reporting caught up. But MPX is still spreading. This is a very common pattern with new outbreaks.

The above counts do not include cases where the virus is endemic, like Nigeria, Cameroon, and Ghana. Endemic countries have reported 59 confirmed cases, 1536 suspected cases, and 72 deaths thus far. The WHO is making a conscious effort to remove the distinction between endemic and non-endemic counts in their reports. They hope this reflects the unified response that is needed; we are all in this together.

In the U.S., the CDC reports 201 cases across 26 states. Some cases are not linked to travel, which indicates local community transmission is occurring. The CDC has not shared where this may be happening. The majority of cases in the U.S. have not been severely ill; however, some have been hospitalized for pain management. It’s not a walk in the park, as this Tweet thread indicated.

The U.S. count is likely a substantial underestimate of “true” cases. There has been significant tension and frustration about testing capacity. All tests have to go through U.S. public health labs, which can be challenging to access, can take time, and can only process about 8,000 tests per week. Starting in July, commercial laboratories (like LabCorp) are authorized to perform MPX tests. This means tens of thousands of tests could be conducted weekly. There are also testing bottlenecks at the point-of-care. Patients are not seeking testing and healthcare providers are not thinking “This rash could be monkeypox, so let’s test for it.”

Since my last update, we continue to learn quite a bit from rapidly unfolding science:

Genetic epidemiology. It’s clear now that MPX has been flying under the radar for a few years outside of Africa. A U.K. report suggested that the global outbreak may be three separate events. This theory is shaping up in genetic testing, as seen below. Published lab data also show the current virus has far more mutations than expected and several that can increase transmission.

We are getting tighter estimates of R(t). Now that we have more data, we can better estimate infectiousness. There is currently a doubling time of 17 days and R(t) of 1.51 (ranges from 1.02-2.21). In other words, every infected person infects, on average, 1-2 others. (For reference, the R(0) of smallpox = 3 and Omicron=10.)

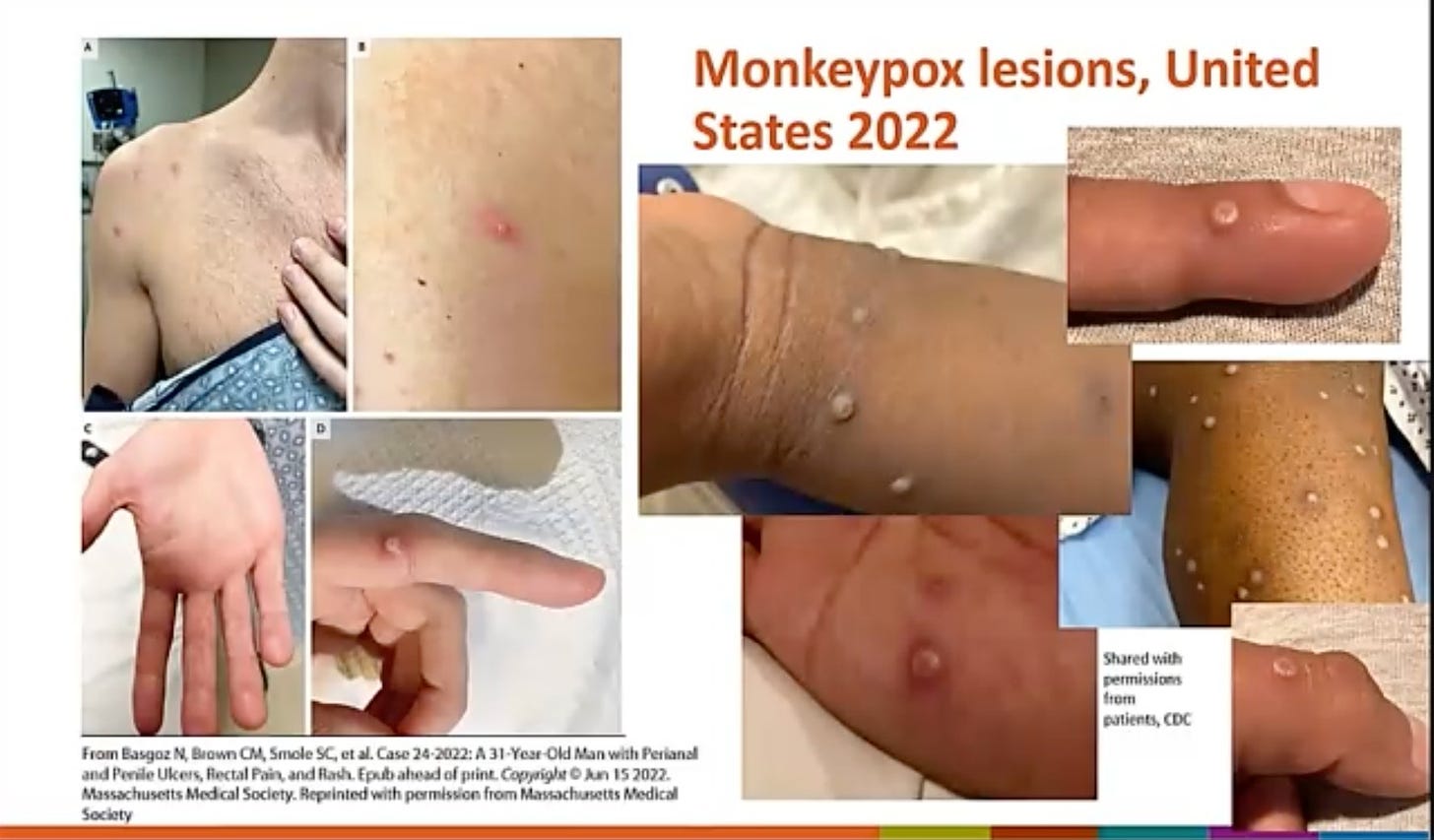

Clinical presentation is different. Some cases aren’t presenting with the typical timeline of symptoms. Historically, MPX starts with swollen lymph nodes and a fever and then a rash appears 3-5 days later. Now, some are presenting with the skin lesions, specifically in the genital region, then having a fever (or not having a fever at all). Below are images of lesions in the current outbreak in the U.S. I’m not surprised this was flying under the radar.

Spread through semen. One of our biggest questions was whether live virus is present in semen and vaginal fluid. This was confirmed in Italy and Germany. The studies were small, so much more research is needed to distinguish transmission from semen and/or close contact. But in the short-term, recommending condom use during infection and for time time afterwards as a prevention strategy is needed. U.K. has already implemented this.

Vaccine supply and decisions. Last Thursday, ACIP met to discuss vaccine policy for MPX. As of June 14, the U.S. had more than 36,000 vaccine courses in supply and 500,000 will be delivered in the next year. CDC is working on recommendations for expanded use of the MPX vaccine, keeping in mind the currently limited supply and the health risks associated with use of the other smallpox vaccine (which should offer some protection). But it’s not clear how great vaccine uptake will be. In the U.K., for example, only 69% of health workers who had contact with cases agreed to be vaccinated; among other contacts of the cases, only 14% wanted the vaccine. Given the lines for a MPX vaccine in NYC Friday (see below), we may have better uptake in the U.S.

Bottom line

We still only (!) have two PHEIC at this time; the WHO is keeping an eye on MPX. To say it’s a wild time to be an epidemiologist is an understatement.

The risk of MPX to the general public remains low. Some people are at increased risk, like those in MSM networks in which this is virus is dominating. Be aware of the symptoms and ways to reduce your risk.

Love, YLE

“Your Local Epidemiologist (YLE)” is written by Dr. Katelyn Jetelina, MPH PhD—an epidemiologist, biostatistician, wife, and mom of two little girls. During the day she works at a nonpartisan health policy think tank, and at night she writes this newsletter. Her main goal is to “translate” the ever-evolving public health science so that people will be well equipped to make evidence-based decisions. This newsletter is free thanks to the generous support of fellow YLE community members. To support the effort, please subscribe here:

Is there even limited data on how effective the original smallpox vaccine (received by many of us decades ago) might be? Would that be important, not only for prevention, but in determining priority for vaccination?

I don’t understand your headline, esp the all caps, when you disagree w it ~ “ Wouldn’t we want a PHEIC to prevent these terrible things from happening? We must get out of this reactive response mode. The window to stop this virus is closing. As Professor Michael Worobey said:

“This is like deciding to snooze for an hour when the smoke alarm goes off to be good and sure it's a real fire. Time to realize it's smart to get out of bed even for false alarms now & then.””